The Domain of Primary Care

This chapter explores the domain and scope of primary care, beginning with an examination of the evolving definitions of primary care medicine and ending with an affirmation of the enduring principles supporting it. The definitions derive from organizational models of care, from its clinical content, from its functions within systems of care, from the disciplines that contribute relevant research for education and practice, and from primary care practitioners’ professional identities. Understanding these definitions, and the historical circumstances of their emergence, primary care clinicians and students can gain clarity not only about the work of their chosen careers but also about the enduring principles of their profession.

DEFINITIONS AND SPECTRUM OF PRIMARY CARE (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27 and 28)

Each of the definitions of primary care can best be understood in terms of the historical context in which they emerged or gained prominence. For example, it is the functional definition that is most prominent in the United States as it works to implement meaningful health care reform. Primary care is strongly associated with access to care as well as its comprehensiveness, continuity, and coordination. Because these functions are recognized by all stakeholders as the most tender of the pain points in the current system, reinvention of primary care and the system in which it resides is seen as the needed solution. However, without considering each of the definitions and the policy and political forces that have given them prominence, we risk creating a limited future for primary care that would forgo value for patients and society.

A Systems Definition: Primary Care as the Site of First Contact and Continuous Care (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8)

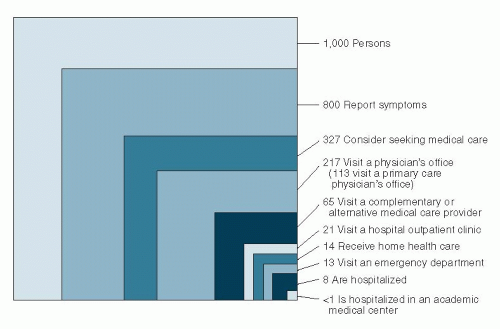

The phrase “primary medical care” was first used in 1961 in an examination of what Kerr White and colleagues called the “ecology of medical care.” Based on an examination of communitybased physicians and their patients, that examination revealed the following monthly incidences of illness and medical care among a population of 1,000 adults: 750 reported one or more illnesses or injuries; 250 consulted a physician one or more times; 9 patients were admitted to the hospital; 5 patients were referred to another physician; and 1 patient was referred to an academic medical center. A decade later, annual incidences among 1,000 adults showed that the fundamental relationships still held.

In 2001, the ecology of medical care was examined again. Monthly incidences of care-seeking behavior now encompassed children as well as adults, including those who considered seeking care as well as those who actually did so from primary care practices, specialists, complementary medicine practitioners, hospital clinics or emergency rooms, or in the home. The results displayed in Figure 1-1 demonstrate that the fundamental relationships changed little over 40 years.

What had changed was an understanding of how these relationships and the care that people receive vary from one geographic region to another. Inspired by White’s conceptualization of the ecology of medical care, John Wennberg developed rigorous methods to study the epidemiology of medical care across geographic regions. He found striking variation in the rates of hospitalization and diagnostic and therapeutic procedures that could not be explained by differences among patients or their access to primary care services. With colleagues at Dartmouth, he later extended these methods across the United States, compiling The Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care, first published in 1996. Rates of visits, hospitalizations, and major imaging were strongly associated with local supply of hospital beds, specialists, and imaging equipment. The greater intensity of services driven by supply added up to more than threefold differences in per capita health care costs for Medicare beneficiaries among the regions, yet functional outcomes and mortality were no better and perhaps worse. Patient and physician perceptions of access to services and their quality were also lower in the high-intensity hospital referral regions. Interestingly, even primary care doctors from high-intensity regions test and treat more often and more intensively.

Primary care’s place in the ecology of medicine was evocatively described at a WHO conference held in Alma Ata in 1978. The reduction in rates of infant mortality and infectious disease achieved by Chinese “barefoot doctors,” (the backbone of the Chinese rural care system) and the integration of their first-contact, continuous medical care for individuals with public health measures for populations inspired conference participants. The Declaration of Alma Ata included a recommendation for investments in primary health care systems everywhere as a means of achieving health care as a basic human right.

A Task-Oriented Definition: The Work of the Primary Care Clinician (9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18 and 19)

The first edition of Primary Care Medicine began by defining the tasks of primary medical care to include the following: medical diagnosis and treatment; psychological diagnosis and treatment; personal support of patients of all backgrounds in all stages of illness; communication of information about prevention, diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis; and the prevention and care of chronic disease through risk assessment, health education, early

disease detection, and behavioral change. It is the integrated performance of these clinical tasks that defines and comprises primary care work. They are not separable in practice, but some elements deserve special consideration.

disease detection, and behavioral change. It is the integrated performance of these clinical tasks that defines and comprises primary care work. They are not separable in practice, but some elements deserve special consideration.

Integrating Medical and Psychological Diagnosis and Treatment

When patients present to primary care practitioners with common symptoms such as palpitations, headache, or fatigue, it is often unrecognized anxiety and/or depression that contributed most to their decisions to seek medical care and to the symptoms themselves. A clinician trained to recognize the psychosocial determinants of these presenting complaints and communicate effectively with patients can be more discerning in the use of diagnostic tests to detect physical etiologies. The result is often better care and better health at lower cost.

Just as recognition of the patient’s anxiety and/or depression helps in the interpretation of the presenting bodily complaints, it also helps the clinician to provide meaningful support and respond appropriately to the patient’s emotional needs. Providing effective support often begins with elicitation of patients’ attributions of symptoms, and their expectations for treatment, as well as any requests they may have.

Eliciting and Responding to Attributions, Requests, and Preferences

To inform, explain, reassure, and advise patients are tasks that are essential to providing support. These communication tasks often depend on knowledge of the patient’s attributions, requests, and preferences.

Attributions.

What the patient thinks is the cause of illness is his or her attribution(s). If the patient’s attributions differ from the doctor’s and are not uncovered, the patient’s anxieties may not be relieved, nor will the doctor’s explanation be accepted. Such confirmation or correction of the patient’s attributions is a kind of “attribution therapy.” Attributions serve a major function in all medical care systems—namely, the control of illness through the explanation of its cause.

Requests.

Requests also deserve attention. Defined as specific, concrete helping actions and behaviors that patients want, these essential elements of the patient-doctor interchange require prompt recognition and often negotiation; however when elicited and responded to, both patient and doctor benefit. The doctor’s interest in ascertaining the patient’s needs and wants establishes reciprocity as an element of the relationship and is associated with greater satisfaction and adherence to medical advice. Continuing care, referral, discharge, informed consent, and end-of-life preferences are some of the many decisions negotiated through an understanding of patient requests.

Preferences.

Truly patient-centered care is impossible without the effort to assist patients in constructing their informed preferences for different health outcomes and the treatments that make them more or less likely. Recognizing the symmetry in the importance of professional and personal knowledge in making the right choices in the care of individual patients, this process has been called shared decision making. More recently, to emphasize the clinicians’ responsibility to assist the patient in reaching an informed preference in choosing among care options, the term preference diagnosis (and the often silent but all-too-frequent “preference misdiagnosis”) has been introduced. Registries of patient preferences for common health outcomes and treatments that contribute to them have been advocated in an effort to stop these silent misdiagnoses (see Chapter 5).

Mastering Use and Interpretation of Diagnostic Tests

Mastery in use and interpretation of diagnostic tests is essential, especially in settings where there is relatively little evidence to definitively guide clinicians. Test overuse leading to overdiagnosis and overtreatment is a major contributor to waste and harm in health care. Skills drawn from clinical epidemiology enable discerning use and critical interpretation of diagnostic tests; they are essential for primary care clinicians (see Chapter 2).

The use of screening tests to detect disease before the patient experiences signs or symptoms is a special case in the use of diagnostic tests. In many cases, the promise of early detection is not realized. Overdiagnosis and overtreatment that produce psychological and physical morbidity is especially troubling when it is visited upon the previously healthy patient. Again mastery of elements of clinical epidemiology is essential to base such decision making on evidence rather than enthusiasm (see Chapter 3).

Interpreting the Medical Literature and Applying It to the Care of Individual Patients

Choice of treatment requires special expertise in interpreting the medical literature as it applies to the individual patient. How strong is the evidence that a therapy will provide more benefit or less harm or both when compared with other approaches including watchful waiting or active surveillance for a period of time? How do different patients feel about the outcomes, about the risks of complications or death, and about trade-offs over time? Different patients often feel quite differently about the same outcomes and treatments. When that is the case, the patient’s preference diagnosis is as important in choosing therapy as is the disease diagnosis (see Chapter 5).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree