Key Clinical Questions

Introduction

The term difficult patient refers to a subgroup of patients that provoke unpleasant emotions—feelings of frustration, anger, helplessness, inadequacy, or irritation—in the doctors caring for them. These patients are described in the records of the earliest physicians. Thomas Sydenham wrote in his famed treatise on hysteria “All is caprice. They love without measure those whom they will soon hate without reason. Now they will do this, now that; ever receding from their purpose.” These patients have a series of overlapping characteristics, shown in Table 230-1.

|

Although many authors see conflicts between clinicians and patients as specific to one dyadic relationship, most patients identified as difficult or disordered have a long history of failed medical relationships and are often dissatisfied when they arrive. They recreate the same dissatisfying relationships by repeating the behaviors that caused their previous experiences. Emotionally provoked staff members will likely behave in ways that only further confirm the patient’s expectation that he or she will receive poor treatment.

Many neurologic disorders and medical conditions, including tumors, endocrine and autoimmune disorders, and medications, cause psychiatric syndromes, such as personality changes, major depression, cognitive dysfunction, and executive dysfunction. All of these can result in behaviors that make patients “difficult.” The following discussion is organized around the psychiatric conditions that provoke and sustain “difficult” behaviors, and introduces the concept of a behavioral approach to managing these patients.

A 28-year-old man with HIV and hepatitis C presented to the hospital for a complicated cellulitis and abscess of hand and forearm that developed after an altercation. The emergency room physician performed an incision and drainage and admitted him to the hospital for intravenous antibiotics. The patient acknowledged occasional nasal heroin and cocaine use but denied addiction. At the time of admission, the attending ordered oxycodone 10 mg every six hours as needed. The health care team suspected that the patient was homeless when he refused to provide a telephone number or family contact. During multiple prior admissions the patient had displayed such hostility that nurses limited their interactions with him. The nurses reported the smell of tobacco smoke near the patient’s bathroom, but he declined a nicotine patch. He left the floor to smoke and often returned appearing sleepy and intoxicated. He received escalating doses of intravenous (IV) narcotic medication from cross-covering clinicians. The day team did not appreciate that his night time extra doses amounted to a significant escalation of his opiate use. His readmissions precluded follow-up with his primary care physician from another hospital network. Multiple attending physicians during his monthly hospitalizations further disrupted continuity of care. On hospital day 2, the patient refused his dressing changes without IV narcotics. The nurse reported that she tried to coax the patient to undergo a dressing change with oral opiates but that he started yelling obscenities at her. Extremely irritable, the patient was alternately pleading and demanding IV pain medications. He threatened to leave if “the people here don’t start treating me with respect.” This patient’s hostility made his primary nurse feel defensive and uncomfortable. THE ROLE OF LIFE EXPERIENCES AND ASSUMPTIONS At this point, a psychological and social history revealed that the patient had grown up in east Baltimore under the worst of conditions. His physically abusive father abandoned his family. His mother was largely unreliable due to substance abuse. After asking numerous questions about his past medical experiences, we determined that the patient had received medical care only in “institutional settings,” and his experience with white male authority figures had been dismal. We discussed his history of negative interactions with health care in institutional settings, and how his “assumption” that he will be mistreated leads to antagonistic behavior toward nurses and doctors, who respond in turn with hostility. After commenting on how unfortunate these experiences must have been, we informed him that we would like to start with a clean slate. We reinforced our commitment to getting him better and to trying to make his stay as comfortable as possible while still doing what would be medically justified by the risks and benefits of treatments. We negotiated with the patient that if he wore a nicotine patch, cooperated with dressing changes, and restrained from foul language, one of us would accompany him outside to smoke twice a day. Although he could not receive IV opiates, he would receive his preferred opiate orally, hydromorphone (Dilaudid) in equianalgesic dosing to the oxycodone he had been prescribed. THE BENEFITS OF INITIATING TREATMENT OF DEPRESSION IN THE HOSPITAL His behavior improved. The diagnosis of depression would not have been made had it not been for the extended exposure to the patient in the setting of walking him outside. While smoking, he described his life as miserable and meaningless. He stated that he could not sleep at night and felt “hateful” all of the time. He said he often thought he would be better off dead and admitted that he sometimes hoped someone, “like a police,” will shoot him. We offered him medications for sleep and depression and described major depression to him. The treatment of his depression allowed the forging of a better relationship as we discussed the way his depression had interfered with his life. PATIENT EDUCATION ABOUT WHAT IS GOOD AND BAD ABOUT EXTRAVERSION We told our patient that he needed to choose between being Martin Luther King Jr., who had rules he followed even when he was angry, sad, or felt like he was not getting anywhere, and being Marion Barry, who, when he got caught smoking crack with a prostitute said “it wasn’t me.” I described to the patient that he had “special abilities to persuade people” so that he usually got his way, but that he was using those powers to harm himself and those around him. He was able to expand this and engage with the idea. NONJUDGMENTAL RECOGNITION OF ADDICTION On day 3 he was much more irritable, with nausea and flulike symptoms. We diagnosed him with opiate withdrawal and offered to treat him for his withdrawal with higher doses of opiates followed by a slow taper. We described how addiction can sneak up on people. At this point, we also introduced the idea that some people have very little emotion, most people have an average amount of emotion, but that he had a very large amount of emotion, using the term “two scoops of feelings.” We explained that this was a form of being “gifted,” but for him it had been a curse. We clarified that his belief that he should be having a better life was actually accurate, but that no one had helped him learn to manage his intense feelings. We offered to help him with this over the several subsequent days. We added a long-acting opiate to stabilize him on a regimen. During the remaining days of his admission, we slowly tapered his opiates and offered to refer him to an outpatient program if he wished. The medical team saw him twice a day, often confronting him gently on the way his feelings cause him problems and with suggestions on how to behave during intense feeling states in order to be more effective. THE IMPACT OF THE DOCTOR–PATIENT RELATIONSHIP AND SYSTEM OF CARE ON OUTCOMES Consider the example of our patient, who had multiple readmissions to a tertiary hospital outside of his network. He seemed to benefit from hospitalization as a possible way to obtain temporary shelter and food, receive intravenous narcotics that made him feel better, and perhaps experience fewer restrictions than in the city hospital where he was enrolled in care. When asked why he did not go back to the hospital of his primary care physician, he responded, “They do not treat me right.” The challenge for the clinicians taking care of him was how to change the behavior resulting in monthly readmissions. We determined that the plan would be most successful if directed by one primary care physician. We ascertained through communication that his primary care physician would accept him back and manage his HIV and other medical issues as well as his substance abuse. Because he would likely benefit from the direction of one individual, he was transferred to the hospital of his primary care physician. Although not customary practice, this may have been the only way to break the cycle of readmissions so that appropriate resources could be put in place to provide him with the help he needed. |

Pathophysiology

Studies of difficult patients are fraught with technical challenges but have generally found that about 15% of patients are perceived as difficult. Six psychiatric disorders had particularly strong associations with being labeled as difficult: somatoform disorder, panic disorder, dysthymia, generalized anxiety, major depressive disorder, and alcohol abuse or dependence. The presence of mental disorders accounted for a substantial proportion of the excess functional impairment and dissatisfaction of difficult patients, but not for all of it. It is not surprising that these “difficult” patients often develop symptoms that precipitate hospitalization for potentially serious symptoms, noncompliance with treatments, or, sometimes, as a result of outpatient or emergency department physicians’ lack of time or patience.

Our organizational rubric is developed out of the elegant work of McHugh and Slavney in Perspectives of Psychiatry. We will first discuss the psychological precedents from the patient’s life experiences. This is followed by a discussion of the role of psychiatric disease states, problematic personality traits, and behavioral conditioning and addictions. Patients often have more than one related condition, each exacerbating the others (Table 230-2).

|

|

The Role of Life Experiences

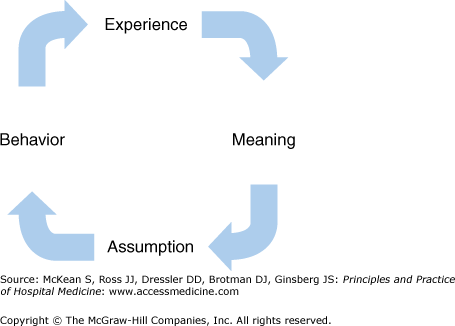

Life experience is difficult to subject to randomized clinical trials and does not fit well into “evidence-based medicine.” Figure 230-1 illustrates the cycle of life experience and how behavior develops out of the assumptions one makes about the world. This cycle can be interrupted at any of the arrows shown. Patients must understand the psychological precedents that shape their behavior, and they need a clinician who is willing to confront their behavior and guide it toward more adaptive and successful function. (Refer to preceding case study.)

Commitment to acceptance of any goals patients bring, even unhealthy goals, undermines these patients’ need for guidance and direction from the clinician, much to their detriment. To defuse this dynamic, the clinician may communicate that the patient is very important despite their misbehavior and that the health care team wants to help. Changing this cycle of hostility requires tackling some of the patient’s assumptions and establishing the critical core of the doctor–patient relationship. Patients can fire you and go elsewhere, but they cannot prescribe their own treatment.

Psychiatric Diseases

Patients with major mental illness have higher rates of mortality and medical morbidity. As a group they have poorer compliance with medical interventions and exhibit high-risk behaviors and unhealthy habits resulting in higher rates of medical complexity and comorbidity. In most health care systems the chronically mentally ill are disenfranchised from medical care. They take more time and are more challenging to treat than other patients. Frequently underinsured, they have poor access to medical care and decreased willingness to take advantage of accessible care. Specific mental disorders tend to be associated with different types of difficult behaviors.

|

Schizophrenia is a progressive, disabling, lifelong, chronic mental illness characterized by a stepwise deterioration of executive function, social interactions, and a paranoid psychosis without return to baseline between episodes. Patients more often focus their paranoia on outside agencies and people regularly in their lives. The so-called positive features—the auditory hallucinations, delusions, and feelings of external control—are episodic and disruptive. The “negative features” include affective flattening (or inappropriate affect), ambivalence, autism (with social withdrawal), and loose associations. The following exemplifies how physician attitudes affect their approach to patients with mental illness and the degree of difficulty inherent in treating these patients:

A man with schizophrenia had the persistent delusion that the VA in Florida was shooting radio waves into his abdomen. He presented with worsening abdominal pain and a seemingly stable 4 cm abdominal aortic aneurysm. For two weeks his complaints were attributed to his paranoia despite low-grade fevers and a rising white blood cell count. He died of massive internal hemorrhage shortly after a gallium scan correctly diagnosed his mycotic aortic aneurysm. Physicians often approach clinical interactions with the preconceived notion that all complaints by patients with schizophrenia are generated by the illness, or that they will be unable to follow treatment recommendations—an assumption that is often incorrect. |

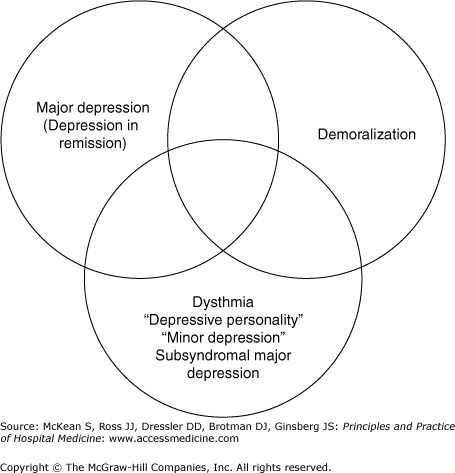

The term depression denotes a symptom, a complaint, and several conditions that are probably biologically determined syndromes caused by brain dysfunction. Depressed patients are often lumped together in studies and included or excluded by symptom scales rather than strict criteria, making the literature difficult to understand. There are at least three separate conditions to be considered when thinking about depression, namely, demoralization, chronic dysthymia, and major depression (Figure 230-2).

The term demoralization describes those patients suffering from the expected or understandable psychological state of decreased mood associated with adversity, loss, and grief. Ranging from mild to severe, demoralization can lead to suicide, social withdrawal, and serious medical morbidity. It responds to the “tincture of time,” support, encouragement, and reintegration into occupational, social, and recreational activities. Most physicians do not perceive these patients as difficult; they often evoke genuine sympathy and are usually grateful for the counseling, encouragement, and guidance they receive.

Dysthymia has come to mean chronic major depression, depressive personality style, and subsyndromal major depression. The term as used here denotes a chronic pessimistic personality style, but the term is frequently used in other ways. These patients are like Eeyore in Winnie the Pooh, chronically negative but usually quite functional unless they encounter circumstances where their personality style interferes with their function. Their chronic pessimism can lead to frustration on the part of the physician caring for them.

Dysthymic patients latch onto doctors and try to get the doctor to make them feel better emotionally when they constitutionally resist doing so.

Dysthmic patients This quote from Winnie the Pooh is illustrative: (Eeyore the donkey) “Hallo, Pooh. Thank you for asking, but I shall be able to use it again in a day or two.” “Use what?” said Pooh. “What we were talking about.” “I wasn’t talking about anything,” said Pooh, looking puzzled. “My mistake again. I thought you were saying how sorry you were about my tail, being all numb, and could you do anything to help?” “No,” said Pooh. “That wasn’t me,” he said. He thought for a little and then suggested helpfully: “Perhaps it was somebody else.” “Well, thank him for me when you see him.” |