Introduction

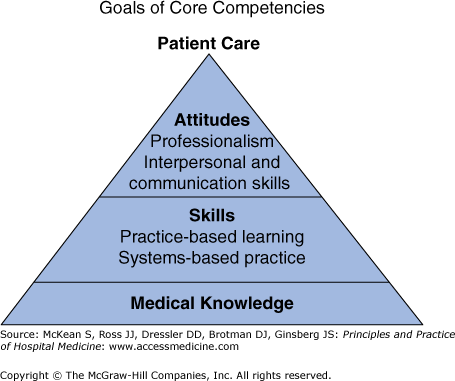

Initially, the hospitalist movement arose to reduce length of stay by having dedicated physicians in the hospital most of the time. Over time, the role evolved, and it became clear that hospitalists could improve the quality of inpatient care, promote patient safety, and educate the next generation of physicians. Although the term hospitalist was coined in 1996, over the subsequent decade there remained considerable variability in the definition of hospitalist and the scope of work attributed to that role from one practice setting to the next. At the same time that Hospital Medicine leaders embraced the importance of evidence-based care and systems improvement—especially around transitions of care and the well-publicized safety and quality issues facing hospitalized patients—they were recruiting physicians from traditional residency programs that had not adequately prepared them for their new roles. In fact, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) acknowledged training gaps in six main competency areas for evaluation of medical trainees: patient care, medical knowledge, practice-based learning improvement, interpersonal and communication skills, professionalism, and systems based learning.

The Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) recognized the need to define specific competencies of a hospitalist to establish performance standards, differentiate Hospital Medicine as a unique subspecialty, and create a framework for training programs. SHM hoped that the creation of a document detailing core competencies would further serve to standardize training programs, highlight training gaps within internal medicine residency programs, and identify the professional development needs of practicing hospitalists. In 2006, SHM developed and published The Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine: A Framework for Curriculum Development. This document is a compendium of competencies for the practice of Hospital Medicine and was developed by SHM in conjunction with more than 100 hospitalists and physician leaders from university and community hospitals, teaching and nonteaching programs, and for- and not-for-profit programs throughout the United States (Figure 5-1).

| Care of Vulnerable Populations Competencies | ACGME Core Competencies | Transitions of Care Competencies |

|---|---|---|

| Development of a formal curriculum around vulnerable populations reflects attitudes that care should be patient centered. | Patient care | Utilize the most efficient, effective, reliable, and expeditious communication modalities in patient transitions. |

| Teach that for vulnerable populations “business as usual” may be inadequate, and additional resources may be required to reach target goals. | Organize and effectively communicate medical information in a succinct format for receiving clinicians. | |

| Expect students to proactively arrange for these services and provide feedback when this does not occur. | Recognize the impact of care transitions on patient outcomes and satisfaction. | |

| Identify the key factors that lead to vulnerability, describe the needs of populations served and local resources available to ameliorate barriers to Healthcare provision. | Knowledge | Describe information that should be retrieved and communicated during each care transition (eg, key elements involved in signing out a patientmoving to the intensive care unit or going home). |

| Use the core competencies to develop activities, reading lists, bedside teaching, didactic sessions, and innovative educational forums. | Distinguish available levels of care for patient transition and select the most appropriate option (eg, Long Term Acute Care, rehab, Skilled Nursing Facility, psych facility, other facilities). | |

| Formally evaluate social history-taking skills and construction of patient-centered care plans through direct observation and feedback sessions, attending rounds and bedside discussions | Practice-based learning and improvement | Inform receiving physician of pending tests and determine who is responsible for follow-up on results. |

| Solicit patient feedback on the trainee’s performance. | Incorporate quality indicators for specific disease states into care plans. | |

| Develop a social curriculum which reflects attitudes that trainees should be taught interpersonal and communication skills and professional role modeling. | Interpersonal and communication skills | Communicate with patients and families to explain their condition, ongoing medical regimen, follow-up care, and available support services |

| Use interpreters to effectively educate patients about their problems and engage them in their treatment. | Prepare patients and families early in the hospitalization for anticipated care transitions. | |

| Make hidden goals and expectations explicit through role modeling and informal discussions. | Professionalism | Appreciate the value of real-time interactive dialogue between clinicians during care transitions. |

| Taking a resident on a home visit can be a particularly powerful way to promote professionalism. | Maintain availability to discharged patients for questions between discharge and follow-up outpatient visit. | |

| Resident research projects might relate to the study of disparities of Healthcare, especially among black and Latino populations at your institution. | System-based practice | Lead, coordinate, or participate in initiatives to develop and implement new protocols to improve or optimize care transitions (eg, medication reconciliation form development). |

| During ambulatory rotations, trainees would be expected to report on local resources, develop a social curriculum that could be used to teach trainees, standardize communication for vulnerable patients in their residency clinic. | Engage stakeholders (eg, inpatient clinicians, outpatient clinicians, nurses, administrators) in hospital initiatives to continuously assess the quality of care transitions. |

Since the publication of TCCs in 2006, the evolution of the field of Hospital Medicine continues to present new opportunities not only for growth but for the development of expertise in areas not integrated into residency training. Hospitalists now specialize in the management of medical subspecialty patients, neurology patients, obstetrics, palliative care, critical care, and surgical comanagement. Tertiary care settings have increasingly become large intensive care units with step-down capacity for every patient whose preexisting comorbidities shape recovery. Hospitalists working in community settings may in fact become the teachers of the next generation of residents and medical students as they increasingly rotate through these settings. Although it may not be possible to predict the next stage of evolution, hospitalists are uniquely positioned to support accountable care and optimize integration and performance for the communities their hospitals serve. TCCs are the first step in the process of defining expectations for this young specialty and serve as a template for future educational initiatives.

What Are the Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine?

TCCs standardize expected learning outcomes for teaching Hospital Medicine in medical school, postgraduate (ie, residency, fellowship), and continuing medical education programs, while allowing flexibility for curriculum developers to customize instructional strategies and context, as they integrate the most timely literature and evidence into medical content.