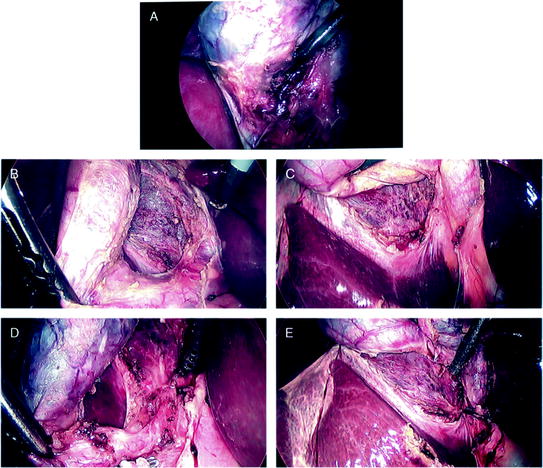

Fig. 9.1

The assistant grasps the fundus cephalad and retracts this toward the patient’s right shoulder. This reduces redundancy in the infundibulum and exposes the cystic duct. A second grasper retracts the infundibulum laterally to make the cystic duct perpendicular to the common bile duct and again to separate the gallbladder from the common bile duct. From Hunter et al. [2, Fig. 1], with permission of Elsevier

- 1.

30° or 45° high-definition laparoscope

- 2.

Cephalad traction on the dome of the gallbladder

- 3.

Lateral traction on the infundibulum and finding the gallbladder wall and staying on it

- 4.

Dissection from above down to the neck

- 5.

Widely opening the hepatocystic triangle

- 6.

Moving the infundibulum back and forth (wave the flag), repeatedly looking at both sides of the gallbladder

- 7.

Critical view of safety

- 8.

Dividing the cystic duct as close to the gallbladder as possible

- 9.

Never dividing the cystic duct with any cauterizing instrument—if it turns out to be the common bile duct, the resulting ischemic injury will only lessen the chances for a good repair.

A safe technique for laparoscopic gallbladder surgery should ideally proceed with the critical view of safety prior to dividing any important anatomic structure (Fig. 9.2) [3]. Three criteria are required to achieve the critical view of safety:

Fig. 9.2

The “critical view of safety.” The triangle of Calot is dissected free of all tissues except for cystic duct and artery, and the base of the liver bed is exposed. At least one-third of the gallbladder should be dissected off the liver. When this view is achieved, the two structures entering the gallbladder can only be the cystic duct and artery. It is not mandatory to see the common bile duct. From Strasberg et al. [3, Fig. 2] with permission of Elsevier

- (a)

The triangle of Calot is cleared from fibrous tissue or fat

- (b)

The lower one-third of the gallbladder is separated from the liver to expose the proper view

- (c)

Only two structures should be seen entering the gallbladder (cystic duct and cystic artery).

Pitfalls Leading to Bile Duct Injury

Common factors include anatomic variation, acute inflammation, chronic scarring, misperception, and error traps that can lead to bile duct injury. Misperception by the surgeon of what he or she is seeing in the operative field is a common factor in the events leading to a duct injury. Bile duct injury occurs far more frequently from the common bile duct or right hepatic duct misidentified as the cystic duct (meaning normal anatomy) rather than an anatomic anomaly as the etiology of the bile duct injury. The surgeon sees what he or she believes and does not believe what he or she sees leading to injury [4].

Different dissection techniques have been described during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Strasberg and colleagues [3, 5] discuss error traps when performing laparoscopic cholecystectomy. An error trap is an operative approach that works in most circumstances, but is prone to fail under certain circumstances. Because these techniques usually work, the surgeon develops confidence in them and fails to recognize when dangerous circumstances are present; it is important to recognize and avoid these error traps. Common dissection techniques for cholecystectomy include the infundibular, the fundus first (top-down) technique, and the semi-top-down approach 1. For an open cholecystectomy, the cholecystectomy is performed from the top-down—this is the safest approach to cholecystectomy. With the development of laparoscopic cholecystectomy, an infundibulum first approach was technically easier and thus promulgated. Thus, we apply an operation laparoscopically violating principles of safety for open cholecystectomy; this approach contributes to many of the complications with laparoscopic cholecystectomy. The semi-top-down approach and top-down approaches are safer approaches to the operation. When approaching the very difficult gallbladder, top-down is the preferred approach to cholecystectomy, whether open or laparoscopic.

The infundibular technique is a technique that works the majority of the time, but will fail in predictable circumstances, specifically anatomic variation or inflammation. This approach involves starting from the infundibulum and then working toward the fundus. In this technique, it is taught that the taper between infundibulum and cystic duct identifies the cystic duct. In a single view, this can be misleading, especially with any inflammation, short cystic duct, or a “parallel union” cystic duct. In these cases, the common duct can be mistakenly divided, believing it is the cystic duct (‘‘infundibular view error trap’’) (Fig. 9.3) [3]. This produces the classic injury with resection of a portion of the common bile duct; concomitant right hepatic artery injury occurs in 25 % of these cases. The variability of the right posterior hepatic duct includes drainage into the cystic duct, gallbladder neck, or common hepatic duct (Fig. 9.4) [6]. With the infundibular approach to the gallbladder, injury to such an aberrant posterior right hepatic duct would be nearly unavoidable when present.

Fig. 9.3

The deception of the hidden cystic duct and the infundibular technique of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Left appearance to surgeon when a duct appearing to be the cystic duct is dissected first. Note that the duct appears to flare (heavy black line), giving the appearance that the cystic duct has been followed onto the infundibulum. Right true anatomic situation in the case of some classical injuries. From Strasberg et al. [3, Fig. 3], with permission of Elsevier

Fig. 9.4

Common anomalies of the posterior right hepatic duct [6, Fig. 4], with permission of Elsevier]

Conversion from laparoscopic to open cholecystectomy and a top-down approach still harbors danger, as conversion has generally occurred because of inflammation and obliteration of normal anatomic planes. The error trap with a top-down cholecystectomy again is caused by what is normally safe, applied in a dangerous situation. Strasberg states that the worst injuries occur in those patients who undergo conversion from laparoscopic to open cholecystectomy, performed top-down because of marked inflammation and difficult dissection. In the difficult gallbladder, the perceived safe operative plane coming down the medial wall of the gallbladder is obliterated by an inflammatory reaction, which incorporates the right-sided porta hepatis and the common bile duct. Thus, injury is commonly associated with major biliary and vascular injury, at times requiring liver resection for the ischemic injury [5].

The laparoscopic fundus first (top-down) technique mimics an open cholecystectomy. Certainly, with acute inflammation, this is the preferred approach. However, this can be awkward laparoscopically with a normal, particularly a large, gallbladder because of the floppiness of the gallbladder when it is fully detached from the liver. The semi-top-down technique of laparoscopic cholecystectomy combines the advantages of both approaches and minimizes the disadvantages [1]. Dissection is started higher on the gallbladder, above the infundibulum of the gallbladder (Fig. 9.5a–e). The peritoneum is scored circumferentially, lateral side first, coming across the peritoneum over the infundibulum of the gallbladder, and then opening the peritoneum coming up the medial side of the gallbladder, being careful not to enter the cystic artery as you do so. Then, by rolling the gallbladder back and forth, the gallbladder can be largely detached from the liver, leaving only the fundus attached to again provide easy retraction. At this point and only at this point is the infundibulum and its junction with the cystic duct approached, thus generating a top-down approach to the cystic duct and cystic artery. When proceeding with the semi-top-down taking only tissues that you see through clearly, any structures that may be encountered such as an aberrant duct, right hepatic artery, or posterior cystic artery can be seen and avoided. At this point in the operation, what you have generated is an exaggerated critical view of safety. It is now clear which structures are cystic artery and cystic duct; these structures can now be safely clipped and divided.

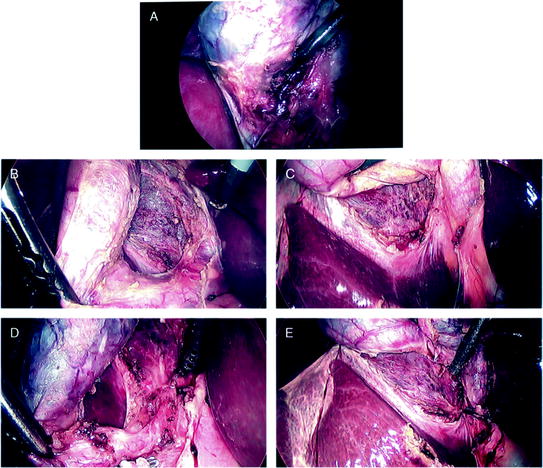

Fig. 9.5

Technique of semi-top-down laparoscopic cholecystectomy. a Dissection is started on the gallbladder, above the infundibulum of the gallbladder. The peritoneum is scored circumferentially, lateral side first, coming across the peritoneum over the infundibulum of the gallbladder, and then opening the peritoneum coming up the medial side of the gallbladder, being careful not to enter the cystic artery as you do so. Dissection of the gallbladder off the liver is being completed here on the lateral aspect of the gallbladder. b and c Then by rolling the gallbladder from the one side to the other, the gallbladder can be fully detached from the liver, leaving only the fundus attached, to provide full exposure. d At this point and only at this point is the infundibulum and its junction with the cystic duct approached, thus generating a top-down approach to the infundibulum, cystic duct, and cystic artery. When proceeding with the semi-top-down taking only tissues that you see through clearly, any structures that may be encountered such as an aberrant duct, right hepatic artery, or posterior cystic artery can be seen and avoided. e An exaggerated critical view of safety has resulted. The cystic artery has been divided, and the cystic duct is clearly defined and ready for clipping and division. From Peitzman et al. [1, Fig. 5], with permission of Wolters/Kluwer

Operative Techniques for the Difficult Gallbladder

Operating on an acutely inflamed gallbladder for acute cholecystitis or hydrops is one of the most common challenges faced by an acute care surgeon. When seeing this laparoscopically and recognizing the need to open for safety, the surgeon must consider how sick the patient is, whether the patient can tolerate an open cholecystectomy, and whether the structures of the porta hepatis be safely avoided before proceeding. If it is clear that the patient is too ill or the anatomy is too hazardous from the inflammation, then cholecystostomy is the appropriate choice. However, when the decision is made to move forward with an open operation in the setting of significant inflammation, hydrops, or difficult anatomy, it should involve a paradigm shift in operative strategy as compared with the straightforward cholecystectomy. The strategy should now focus on the protection of the portal structures by knowing where to be and where not to be—staying only on the wall of the gallbladder (at times submucosa) at all times. The surgeon must know that in this setting, persistent attempts at obtaining the classical critical view of safety can lead to biliary or vascular injury; “no attempt is made to dissect the cystic duct or cystic artery when inflammation obscures the neck of the gallbladder” [7]. The key to the open operation in a difficult gallbladder is finding the wall and staying on/in the wall of the gallbladder. It is important to identify this correct plane and not drift outside of it into the liver bed as this can lead to significant bleeding and can increase the risk of ductal or vascular injury. The middle hepatic vein courses within millimeters of the gallbladder fossa normally with a branch of the middle hepatic vein within the fossa in 20 %. Particularly when performing cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis, drifting off the wall of the gallbladder may result in life-threatening hemorrhage with injury to the middle hepatic vein.

A hydropic, acutely inflamed gallbladder is analogous to an onion with multiple peels of inflammatory tissue. These layers are carefully dissected to safely get onto the wall of the gallbladder (often the submucosa) and complete the dissection in this plane 1. This echos back to the fundamentals of gallbladder surgery—the safest plane for dissection, open or laparoscopic, is on the wall of the gallbladder.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree