Chapter 13 The assessment and care of musculoskeletal problems

Introduction

Musculoskeletal problems account for an estimated 3.5 million Emergency Department (ED) attendances each year. More patients will consult their general practitioner (GP) or treat the problem themselves. The majority of these conditions (sprains, bruises and aches) will be self-limiting, requiring clinical diagnosis, and straightforward treatment and advice.

However, there are diagnostic dilemmas facing the practitioner on the ‘front line’. Even simple injuries often need hospital assessment, usually for X-rays. Some problems are rare but important to diagnose if life- or limb-threatening problems are to be avoided. The skill is to recognise those conditions where urgent referral and treatment are required. The aim of this chapter is to arm the practitioner with these skills (Box 13.1). Major trauma is not covered here.

The primary survey

Patients with a normal primary survey but obvious need for hospital attendance

Certain conditions pose a serious threat to life or limb and must not be missed when considering a ‘wait-and-see’ approach. The conditions listed in Box 13.2 are the ‘red flag’ conditions of the musculoskeletal system.

A major joint dislocation should be reduced as soon as possible, particularly if there is no distal circulation or sensation to the limb. Acutely ischaemic limbs need to have circulation restored within 4 hours to prevent irreversible muscle and nerve damage. Therefore make one gentle effort at relocation. Otherwise the limb needs to be splinted in its current position and urgent transfer arranged.

Secondary survey patients

Assessment of the stable patient

The assessment is carried out according to the recognised system (SOAPC) outlined in Chapter 2. The first step is to decide if the problem is due to trauma or one of the many causes of non-traumatic limb or spinal pain. The spectrum of diagnoses is very different in these two groups.

Trauma vs no history of trauma

Patients who present with no history of trauma should alert the clinician to the possibility of missing Referred pain, Ischaemic syndromes, Sepsis and Kids problems such as epiphyseal abnormalities. Remember the mnemonic RISK. These are the conditions commonly overlooked and can indicate limb- or even life-threatening problems such as cardiac pain, a slipped upper femoral epiphysis or a septic joint.

Subjective information gathering – the history

Definite trauma

Acute trauma is caused by a single, clear event. This can lead to a wide spectrum of injury from minor self-limiting sprains to fractures and/or dislocations of joints. The features of a fracture are pain, swelling, loss of function and bony tenderness. Dislocations are usually more obvious with similar features to fractures plus an abnormal joint morphology with deformity. In the absence of these features then a soft tissue injury is more likely but consider damage to other structures such as ligaments, tendons, nerves and vessels (Box 13.3).

Mechanism of injury

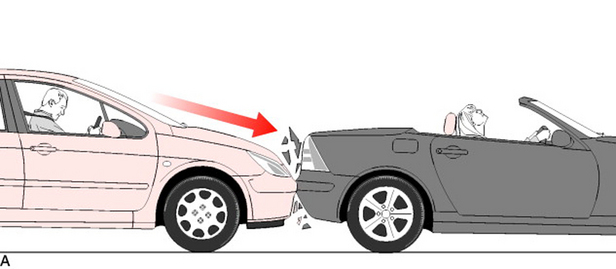

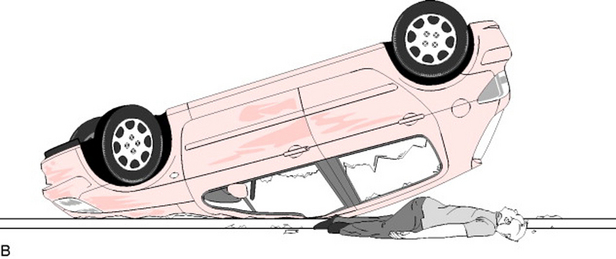

A clear history of the mechanism of injury is essential to accurate diagnosis in trauma. Elicit the magnitude and direction of the forces causing the injury. Simple errors are made by a failure to follow this advice. For example, if the only history obtained was ‘hurt neck in road traffic accident’ the clinician might jump to the conclusion the injury was likely to be a simple neck sprain. However, consider how different your actions might be if a full history were to be obtained such as ‘hurt neck in road traffic accident, was unrestrained front seat passenger in car which overturned at speed’ (Fig. 13.1).

Symptoms and progress

Pain, swelling and loss of function are the main symptoms following injury. Ask if these symptoms have progressed since the incident. A sudden and complete loss of function at time of impact increases the risk for a more severe injury. Ask about associated symptoms such as paraesthesia and trauma elsewhere.