KEY POINTS

The acute abdomen presents in unusual ways in the intensive care unit (ICU).

Successful management depends on prompt diagnosis and management; the intensivist, surgeon, gastroenterologist, and radiologist must collaborate effectively.

Computed tomography (CT) and ultrasonography should be used liberally to evaluate abdominal conditions.

Complications occur frequently in the postsurgical ICU patient; “stable vital signs” does not imply clinical stability.

Postoperative residual or recurrent intra-abdominal sepsis may not be obvious clinically or radiographically; cardiorespiratory or other organ dysfunction should prompt a search for the source that will require resuscitation, antibiotics, and source control

The treatment of the febrile postsurgical patient is not simply the administration of antibiotics.

Acalculous cholecystitis is a treacherous disease that requires urgent treatment; definitive diagnosis is not always possible or necessary before treatment.

Abdominal wall tissue loss or tension may preclude fascial closure at laparotomy. ICU staff must understand and manage postoperatively techniques to protect intestinal integrity and cardiopulmonary function, such as temporary closure and vacuum dressings.

Patients with an “acute abdomen” present challenging problems for surgeons and intensivists. The term acute abdomen refers to a patient whose chief presenting symptom is the acute onset of abdominal pain. The majority of these patients present in the emergency department and need operation but do not require treatment in an ICU. However, the small percentage of patients who require ICU admission constitute a significant fraction of the surgical ICU patients in most general hospitals. Furthermore, the intensivist must be aware that an ICU patient may develop an acute abdominal emergency while being treated for another condition.

In this chapter, we will first discuss the approach to the ICU patient who develops abdominal pain while undergoing treatment for some other disorder. The bulk of the chapter, however, will be directed to the patient with known intra-abdominal sepsis (IAS) who requires intensive care. Emphasis will be placed on the early diagnosis of intra-abdominal septic complications.

EVALUATION OF ACUTE ABDOMINAL PAIN IN THE INTENSIVE CARE UNIT PATIENT

The diagnosis of abdominal pain depends heavily on an accurate history and a complete physical examination.1 Both of these sources of data may be severely limited in the ICU patient. History may be unobtainable because of intubation or a decreased level of consciousness. Physical examination is made difficult by cannulas and dressings, and compromised further by the effects of medications such as analgesics and corticosteroids. Abdominal pain itself may be masked by narcotics or other painful disease processes. Some physical signs, such as the absence of bowel sounds, which would be considered significant in an otherwise well patient, may not be significant in an ICU patient, in whom multiple extra-abdominal causes of ileus may be present. Hence, in the ICU setting, it is rare that an abdominal complaint comes to light because the patient complains of abdominal pain; rather, the physician usually must infer its presence on the basis of nonspecific findings such as unexplained sepsis, hypovolemia, and abdominal distention.

Table 113-1 shows some common causes of acute abdominal pain in North American adults. Rather than describe a complete algorithm to diagnose these conditions in ICU patients, we will list important principles.

Evaluate the patient in the context of the underlying disorder(s). For example, sudden, severe abdominal pain in a patient with congestive heart failure secondary to myocardial infarction is more likely to be due to mesenteric ischemia than to renal colic.

Use surgical consultants liberally. A patient with significant unexplained abdominal pain lasting more than 4 hours should be seen by a surgeon. A patient transferred to the ICU following operation at another hospital should have immediate and continued surgical attendance at the new site.

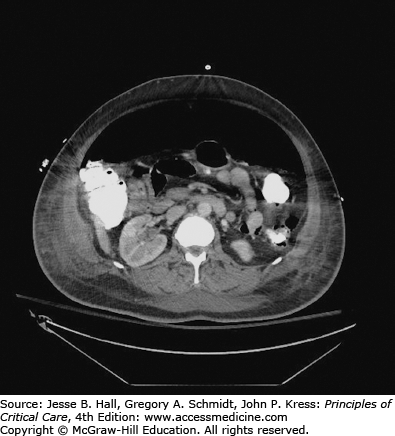

Serum amylase and lipase determinations, and imaging with abdominal CT and ultrasound, should be included in the initial tests for patients with acute abdominal problems when physical examination is unreliable. If these tests rule out pancreatitis, ruptured aneurysm, and retroperitoneal hemorrhage, the patient will often need abdominal exploration to manage intestinal perforation, inflammation, obstruction, or ischemia1 (see Figs. 113-1 and 113-2).

Laparoscopy may help, particularly in patients suspected of having ischemic bowel or acalculous cholecystitis.2-4

Obtain information from family members, previous admissions, and other hospitals and caregivers regarding medical conditions and medications.

Common Causes of Acute Abdominal Pain in North American Adults

| Inflammatory disorders and perforations (eg, cholecystitis, diverticulitis, perforated peptic ulcer, pancreatitis, trauma, infected dialysis catheter) with local or diffuse peritonitis |

| Obstructions |

| Biliary colic |

| Renal colic |

| Intestinal obstruction |

| Vascular |

| Mesenteric ischemia |

| Ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm |

| Intra-abdominal or retroperitoneal hemorrhage |

| Urologic or gynecologic disorders |

| Medical disorders (eg, lupus serositis, sickle cell crisis, myocardial infarction, pulmonary embolus) |

There is no single approach to the ICU patient who develops an acute abdomen, and simply determining that the patient has an acute abdomen can challenge experienced clinicians. Successful management depends on timely diagnosis and the close collaboration of the intensivist and the surgeon.

THE INTENSIVE CARE UNIT MANAGEMENT OF THE PATIENT WITH AN ACUTE ABDOMEN

Most patients with an acute abdomen are diagnosed outside the ICU, and require treatment in an ICU for one of five reasons:

Nonoperative: The patient is very ill but may not require surgical intervention (eg, severe pancreatitis).

Preoperative: The patient requires rapid stabilization or investigation before urgent operation.

Postoperative: The patient requires intensive care for unrelated medical problems (eg, chronic lung disease) following definitive surgical treatment of an acute abdominal condition.

Postoperative: The patient requires intensive care because of severe sepsis or other condition following definitive surgical treatment of an acute abdominal condition.

Interim: The patient requires stabilization before planned reoperation over the next 24 to 72 hours (eg, “damage control” surgery for trauma).

A classification of the sources of IAS appears in Table 113-2. Abdominal infections originating in the pancreas, and infections arising in the urinary tract, are discussed in other chapters.

Classification of Intra-abdominal Sepsis by Source

| Primary peritonitis |

| Infected ascites |

| Infected peritoneal dialysis catheter |

| Miscellaneous (eg, tuberculosis) |

| Secondary peritonitis |

| Intraperitoneal |

| Biliary tree |

| Gastrointestinal tract |

| Female reproductive system |

| Retroperitoneal |

| Pancreas |

| Urinary tract |

| Visceral abscess |

| Liver |

| Spleen |

The key components of treatment of IAS are

Prompt diagnosis and resuscitation

Prompt treatment of the underlying pathology and mechanical cleansing of the peritoneal cavity (“source control”)

Timely, appropriate antibiotic administration

Supportive care of the patient

Vigilant detection and aggressive treatment of complications arising from the underlying condition or its treatment

Close collaboration among all physicians caring for the patient

The importance of prompt diagnosis and treatment cannot be overemphasized. This is one of the few prognostic variables that physicians can control, and prompt treatment has been shown repeatedly to decrease mortality.5-8

Primary peritonitis is a group of diseases characterized by infection in the peritoneal cavity without an obvious source such as a gastrointestinal (GI) tract perforation.9,10 This occurs most frequently in patients with ascites secondary to cirrhosis, congestive heart failure, and peritoneal dialysis, among other disorders. Patients suffering from primary peritonitis rarely require intensive care. However, primary peritonitis may occur in patients requiring intensive care for other reasons. For example, a cirrhotic patient with portal hypertension and ascites may develop primary peritonitis that precipitates hepatic decompensation, leading to variceal bleeding and hypovolemic shock necessitating ICU admission.

The clinical presentation is usually one of fevers and physical signs of peritoneal irritation: involuntary guarding, rebound tenderness, shake and cough tenderness. However, approximately one-third of patients with primary peritonitis have no sign or symptom of sepsis referable to the abdomen. Diagnosis is based on clinical suspicion, the patient’s presentation, and the Gram stain and culture results obtained from ascitic fluid aspiration. Culture of infected ascitic fluid usually yields facultative anaerobic enteric organisms such as Escherichia coli; however, approximately 35% of patients will have negative ascitic fluid cultures.10 Blood cultures may be positive in these patients. Primary bacterial peritonitis may be assumed to be present when the ascitic fluid neutrophil count is >250/µL. The diagnosis may be confirmed in culture-negative patients by a response to appropriate antibiotic treatment within 48 hours characterized by clinical improvement and a decrease in the number of white blood cells present in the ascitic fluid.

It is essential to distinguish primary from secondary bacterial peritonitis, which is caused by contamination from the gut lumen, and in which multiple microbial species are usually found in the ascitic fluid Gram stain or culture.9-10 Patients with secondary bacterial peritonitis are unlikely to respond to antibiotic administration alone, and will usually need surgical treatment to survive.

Antibiotic treatment should be initiated on clinical suspicion of primary peritonitis and before culture and sensitivity results are available. Primary bacterial peritonitis tends to be caused by a single pathogen, usually an enteric gram-negative rod but sometimes gram positive such as Streptococcus pneumoniae, or staphylococcal or Candida species if a dialysis catheter is present. Empiric antibiotics should therefore cover enteric gram-negative rods and gram-positive cocci.11,12 If the diagnosis may be secondary peritonitis so there is concern about distal small bowel, appendix, or colonic derived pathogens, then coverage of obligate anaerobic bacilli is warranted. Treatment with a third- or fourth-generation cephalosporin or quinolone is usually sufficient for primary bacterial peritonitis. For secondary bacterial peritonitis, metronidazole is usually added to this regimen; other appropriate agents include a carbapenem or β-lactam/β-lactamase combination.11 Prognosis of primary peritonitis depends mainly on the severity of the underlying cause of the ascites.

Patients who develop peritonitis secondary to an infected peritoneal dialysis catheter generally improve on antibiotics (usually instilled into the dialysis fluid). Depending on the clinical scenario and peritoneal fluid microbiology, nonresponse may necessitate removal of the catheter, treatment of fungal infection, or consideration of secondary peritonitis of gastrointestinal origin including catheter-induced gut perforation.

The Jaundiced Intensive Care Unit Patient: Sepsis and hyperbilirubinemia occur commonly in critically ill patients. When they coexist, biliary tract sepsis may be the cause. However, most jaundiced ICU patients do not have pathology in their biliary tract.13 Before we discuss biliary sepsis, we will briefly outline the approach to the jaundiced patient.

Abnormalities on liver function tests and even clinically evident jaundice are quite common in patients in the ICU. A review article on jaundice in the ICU13 provides a simple classification, distinguishing jaundice caused by obstructive and nonobstructive etiologies. Most ICU patients with abnormal liver function tests represent the nonobstructive category. Exclusion of extrahepatic biliary obstruction is best accomplished by history, physical examination, and routine laboratory tests (ie, the clinical context),13 ultrasonography to look for bile duct dilation, and magnetic resonance imaging. In unusual circumstances, obstructed bile ducts may not be dilated, and clinical suspicion will necessitate visualization of the biliary tree with endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC), or magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP).14

Infection in the biliary tree can cause one or more of three different clinical entities. The most common is acute calculous cholecystitis, infection of the gallbladder caused by cystic duct obstruction by a gallstone. Treatment generally consists of cholecystectomy, and results in ICU admission if the patient has major medical problems. When a cholecystectomy is deemed too risky because of the severity of underlying or current illness, a percutaneous cholecystostomy can temporize until the patient is more suitable for operation, though some patients never go on to have a definitive operation. More relevant to the intensivist are acute cholangitis and acute acalculous cholecystitis.