CHAPTER 59

Temporomandibular Joint Dislocation

(Jaw Dislocation)

Presentation

The patient’s jaw is “out” and will not close, usually after yawning, taking a large bite of food, or perhaps after laughing, having a dental extraction, or suffering a jaw injury, such as a punch or kick to the mandible, or having a dystonic drug reaction. Such patients have difficulty enunciating clearly. Although they usually have only mild to moderate discomfort, they may have severe pain anterior to the ear. A depression can be seen or felt in the preauricular area, and the jaw may appear to be protruding forward (underbite). If only one side is dislocated, the mandible appears tilted and lies lower on the affected side.

What To Do:

If there was no trauma (and especially if the patient’s jaw is dislocated often), attempt reduction immediately before muscle spasm around the joint makes the reduction more difficult. If there is any possibility of an associated fracture, however, obtain radiographs first. (If available, a panoramic view of the mandible is most accurate.) Excessive pain and tenderness are suggestive of an underlying fracture.

If there was no trauma (and especially if the patient’s jaw is dislocated often), attempt reduction immediately before muscle spasm around the joint makes the reduction more difficult. If there is any possibility of an associated fracture, however, obtain radiographs first. (If available, a panoramic view of the mandible is most accurate.) Excessive pain and tenderness are suggestive of an underlying fracture.

When the possibility of a fracture has been ruled out, have the patient sit on a low stool, with his back and head braced against something firm, either against the wall (facing you) or, as most clinicians prefer, against your body (facing away from you).

When the possibility of a fracture has been ruled out, have the patient sit on a low stool, with his back and head braced against something firm, either against the wall (facing you) or, as most clinicians prefer, against your body (facing away from you).

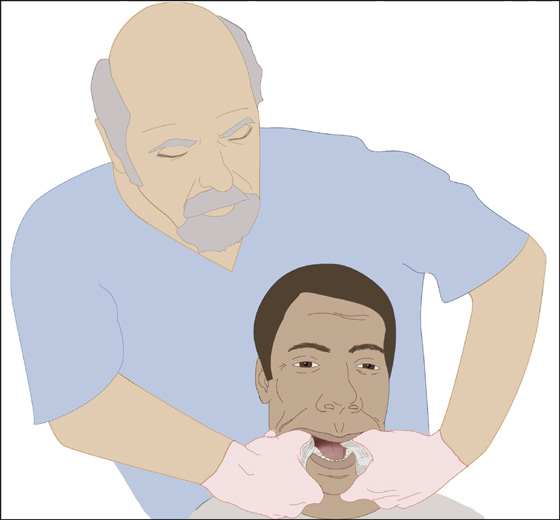

With gloved hands, wrap your thumbs in gauze, place them on the lower molars, grasp both sides of the mandible, lock your elbows, and, bending from the waist, exert slow, steady pressure downward and posteriorly. The mandible should be at or below the level of your forearm (Figure 59-1).

With gloved hands, wrap your thumbs in gauze, place them on the lower molars, grasp both sides of the mandible, lock your elbows, and, bending from the waist, exert slow, steady pressure downward and posteriorly. The mandible should be at or below the level of your forearm (Figure 59-1).

Figure 59-1 Dislocation reduction of the jaw.

In a bilateral dislocation, attempt to reduce one side at a time. This helps to reduce the risk for an inadvertent bite to your thumbs. Use of a bite block may also help to prevent being bitten.

In a bilateral dislocation, attempt to reduce one side at a time. This helps to reduce the risk for an inadvertent bite to your thumbs. Use of a bite block may also help to prevent being bitten.

Successful reduction is usually evident with the sensation of a palpable “clunk.” The teeth will again be able to close easily without malocclusion.

Successful reduction is usually evident with the sensation of a palpable “clunk.” The teeth will again be able to close easily without malocclusion.

If the jaw does not relocate easily or convincingly, it may be necessary to reassess the dislocation with radiographs and to reattempt relocation using IV midazolam to overcome the muscle spasm and 1 to 2 mL of intra-articular 1% lidocaine to overcome the pain. Inject the lidocaine directly into the palpable depression left by the displaced condyle. If you are still unsuccessful, consider using procedural sedation and analgesia, using your institution’s standard protocols (see Appendix E).

If the jaw does not relocate easily or convincingly, it may be necessary to reassess the dislocation with radiographs and to reattempt relocation using IV midazolam to overcome the muscle spasm and 1 to 2 mL of intra-articular 1% lidocaine to overcome the pain. Inject the lidocaine directly into the palpable depression left by the displaced condyle. If you are still unsuccessful, consider using procedural sedation and analgesia, using your institution’s standard protocols (see Appendix E).

A wrist pivot method for temporomandibular joint (TMJ) reduction has been described and may be more effective than the traditional techniques described earlier. While the examiner is facing the patient, who is sitting on a high surface, the mandible is grasped with the clinician’s thumbs at the apex of the mentum and fingers on the occlusal surface of the inferior molars (Figure 59-2). Cephalad force is then applied with the thumbs and caudad pressure with the fingers while pivoting at the wrists until the mandible is reduced.

A wrist pivot method for temporomandibular joint (TMJ) reduction has been described and may be more effective than the traditional techniques described earlier. While the examiner is facing the patient, who is sitting on a high surface, the mandible is grasped with the clinician’s thumbs at the apex of the mentum and fingers on the occlusal surface of the inferior molars (Figure 59-2). Cephalad force is then applied with the thumbs and caudad pressure with the fingers while pivoting at the wrists until the mandible is reduced.

Figure 59-2 The wrist pivot method for temporomandibular joint dislocation reduction. (From Lowery LE, Beeson MS, Lurn KK: The wrist pivot method, a novel technique for temporomandibular joint reduction. J Emerg Med 27:167-170, 2004.)

After the dislocation is reduced, application of a soft cervical collar will reduce the range of motion at the TMJ, which will comfort the patient. Recommend a soft food diet for several days, and instruct the patient to refrain from opening his or her mouth widely over the next 24 hours. Prescribe analgesics if needed.

After the dislocation is reduced, application of a soft cervical collar will reduce the range of motion at the TMJ, which will comfort the patient. Recommend a soft food diet for several days, and instruct the patient to refrain from opening his or her mouth widely over the next 24 hours. Prescribe analgesics if needed.

All patients should be referred for follow-up by an appropriate specialist (i.e., oral and maxillofacial surgeon).

All patients should be referred for follow-up by an appropriate specialist (i.e., oral and maxillofacial surgeon).

If reduction cannot be accomplished using the aforementioned techniques, consider admitting the patient to the hospital for reduction under general anesthesia.

If reduction cannot be accomplished using the aforementioned techniques, consider admitting the patient to the hospital for reduction under general anesthesia.

What Not To Do:

Do not allow your thumbs to be bitten when the jaw snaps back into position. Maintain firm, steady traction, protect your thumbs with gauze, and consider using a bite block.

Do not allow your thumbs to be bitten when the jaw snaps back into position. Maintain firm, steady traction, protect your thumbs with gauze, and consider using a bite block.

Do not apply pressure to oral prostheses, which could cause them to break.

Do not apply pressure to oral prostheses, which could cause them to break.

Do not overlook associated injuries if trauma is involved.

Do not overlook associated injuries if trauma is involved.

Do not try to force the patient’s jaw shut.

Do not try to force the patient’s jaw shut.

Discussion

Certain patients with a congenitally shallow mandibular fossa or underdeveloped condyle are predisposed to mandibular dislocation. Most cases of dislocation occur spontaneously without direct trauma.

The mandible usually dislocates anteriorly and subluxes when the jaw is opened wide. Other dislocations imply that a fracture is present and require referral to a surgeon. Dislocation is often a recurring problem (avoided by limiting motion) and is associated with temporomandibular joint dysfunction. If dislocation is not obvious, consider other possible conditions, such as fracture, hemarthrosis, closed lock of the joint meniscus, and myofascial pain.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree