Key Clinical Questions

What diagnostic testing should be considered for common causes of syncope?

When do clinicians need to rule out arrhythmias and how is this done?

What are the diagnostic criteria for neurocardiogenic syncope?

When do patients require hospital admission?

How do elderly patients differ from younger patients?

How should the history and physical examination be utilized to direct further testing or limit further testing in the evaluation of syncope?

What are the indications for advanced noninvasive or invasive tests in the evaluation of syncope?

Introduction

Syncope is defined as a sudden, transient loss of consciousness and postural tone with rapid spontaneous recovery. Syncope results from cerebral hypoperfusion to the reticular activating system in the brain stem. Any condition that does not result from cerebral hypoperfusion should not be classified as syncope.

A 74-year-old female with early Parkinson disease presented to the Emergency Department with loss of consciousness while standing in the sun. She thought that she did not drink enough water during the day. She initially felt bilateral shoulder pain followed by dizziness, and then recalled awakening on her porch. She injured her forearm, but recovered fully within one minute. A witness described some brief jerking movements in her arms (lasted a few seconds). Blood pressure lying and standing were 130/80 mm Hg and 90/48 mm Hg respectively. Pulse was 86 beats per minute (bpm) lying and 88 bpm standing. Other vital signs, cardiac, and neurologic examination were all normal. An electrocardiogram (ECG) showed normal sinus rhythm with a heart rate of 88 bpm. What is the approach to the patient? What further testing is indicated? What is the diagnosis? What is her overall prognosis following this syncopal event? |

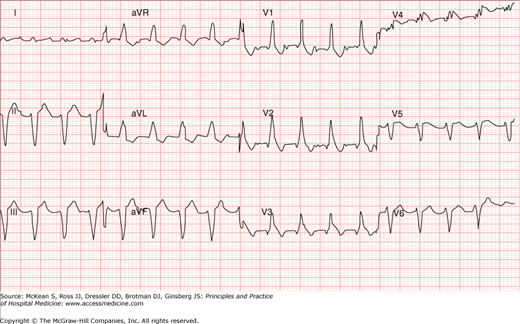

A 62-year-old male passed out while voiding just after awakening from sleep. He denied symptoms beforehand and awakened promptly. On further history, he did not report prior cardiovascular symptoms. His past medical history includes long-standing hypertension and he has a 40-pack-per-year tobacco history. Cardiovascular and neurologic examination was normal. Breath sounds were distant. His ECG is shown in Figure 99-1. What is the best approach to this patient? What further testing is indicated? What is the diagnosis? What is his prognosis if left untreated? |

Syncope has a 3% incidence in the general population and 6% incidence in persons over age 75 years. It is responsible for up to 5% of emergency department (ED) visits and up to 3% of hospital admissions. The median cost of hospitalization of patients with syncope is approximately $8500, and many (up to 50%) may be discharged from the hospital without a clear or specific diagnosis that caused the syncopal episode.

Syncope can present various diagnostic challenges, as many episodes of transient loss of consciousness may occur as unwitnessed events and with limited available history. Furthermore, while the vast majority of syncope etiology is benign, a sizable minority of patients have etiologies with high risk of mortality (ie, patients with cardiac causes). Many testing modalities are also available in the evaluation of syncope, and judicious selection as well as timing and order of the most appropriate modalities can be challenging. Finally, while many patients are admitted to the hospital, up to 40% of patients are discharged without a clear, well-delineated diagnosis following initial workup. However, following extended systematic evaluation (including outpatient evaluation when indicated), less than 20% of patients diagnosed with syncope will remain with a final diagnosis of unknown cause.

Estimates of syncope recurrence suggest that prior syncope, psychiatric illness, and age less than 45 years confer a higher risk of recurrent syncope. Surprisingly, severities of presentation, structural heart disease, and tilt test response have no predictive value on syncope recurrence. Carotid sinus syndrome (CSS), the association of a syncopal event or events with carotid sinus hypersensitivity, has the highest prevalence (43%) in a population of patients presenting with recurrent syncope to the ED. Approximately 12% of patients with recurrent syncope presenting to an ED have associated soft-tissue injury or fracture.

Pathophysiology

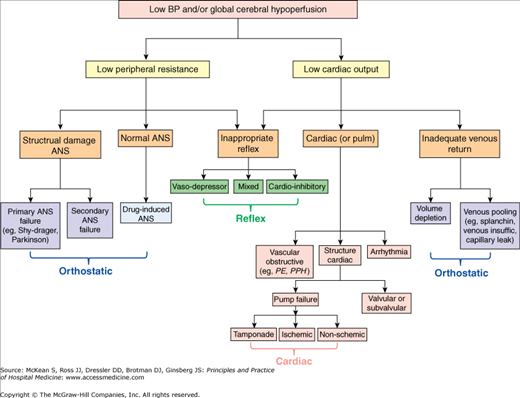

Transient hypoperfusion of the brainstem or both cerebral hemispheres can result from either decreased cardiac output or significant decrease in peripheral vascular resistance. These two mechanisms form the basis of the pathophysiology behind all syncopal events (Figure 99-2). Specific diagnoses (or etiologies of the syncopal episode) may then be derived based on symptoms, signs, and additional testing that lead to their likely pathophysiologic origin.

In patients with traumatic injury (eg, coup-contracoup or concusion injury), transient LOC is not associated with decreased blood flow. In nontraumatic transient LOC, clinicians should consider seizure and psychogenic etiologies. Rarer causes of transient LOC without syncope include tumor, metabolic etiologies, or intoxications. Several conditions may be incorrectly diagnosed as syncope, (ie, “nonsyncope”) (Table 99-1). Clinicians should consider anemia or pregnancy in the appropriate clinical setting.

|

Differential Diagnosis

Syncope etiologies (and relative frequencies) are broadly divided into four major categories (reflex syncope, orthostatic, cardiac, and neurologic) in addition to unknown etiology (Table 99-2). Reflex (most commonly vasovagal) syncope occurs most commonly, followed by cardiac etiologies. More than 70% of cardiac causes are due to arrhythmia, while the remainder is due to various types of structural heart disease.

| Syncope Category | Approximate Frequency | Specific Etiologies |

|---|---|---|

| Reflex Syncope (ie, nerually-mediated, neurogenic, or neurocardiogenic) | 35–40% | Vasovagal |

| Situational (micturition, defecation, cough, valsalva, mobilization after prolonged bed rest, etc) | ||

| Carotid sinus hypersensitivity | ||

| Cardiac | 20–25% | |

| Arrhythmia |

| |

| Structural |

| |

| Orthostatic | 5–15% |

|

| Neurologic | 10–15% |

|

| Unknown | 15–25% |

Following identification of true syncope (ie, excluding nonsyncope based on history, physical exam, and initial testing), narrowing the differential diagnosis should be accomplished based on suggestive clinical features and appropriate diagnostic testing (Table 99-3). The relative yield and contribution of advanced diagnostic modalities in syncope should be considered when selecting modalities in the diagnosis of syncope patients.

| Pathophysiologic Mechanism | Subtypes/Specific Etiology | Examples | Suggestive Clinical/Historical Features | Further Diagnostic Testing to Consider |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Reflex Syncope (vasodepressor or cardioinhibitory) | Vasovagal, from a stress on the orthostatic regulatory system | Emotional hyperactivity, pain, fear of blood. | Precipitating event; nausea, diaphoresis, palpitation, bowel or bladder incontinence prior to attack; eyewitness account; abdominal discomfort; post-prandial; recurrent nature. | ECG Stress test or echocardiogram if history of cardiac disease. If negative, no further testing is needed |

| Carotid sinus hypersensitivity/syndrome | Neck movement; shoulder pain; age > 40; neck tumor, syncope during shaving, due to tight shirt collars. | Carotid sinus massage | ||

| Situational | Valsalva due to cough, micturition, defacation, vomiting. | See examples | None, if heart disease reasonably excluded | |

| 2. Orthostatic Hypotension | Primary ANF | Shy-Drager, Lewy body dementia, multisystem atrophy. | History of neurologic disease. | Orthostatic challenge |

| Secondary ANF | Diabetes, uremia, spinal cord transection/injury, amyloidosis, HIV disease. | History of diabetes, HIV, rheumatologic, oncologic or neurologic disease. | Orthostatic challenge Neurologic testing to establish Dx, as needed | |

| Drug-induced OH | EtOH, diuretics, TCAs, SSRIs, vasodilators | Thorough medication review, including temporal relationship to fall. | Orthostatic challenge. | |

| Volume depletion | Hemorrhage, diarrhea, emesis, iatrogenic | Postural change; timing of standing to falling; prolonged standing; recent alpha-blocker or diuretic. | Orthostatic challenge, volume challenge and retest | |

| Venous Pooling | Postprandial, venous insufficiency | History of timing of syncope; varicosities or peripheral edema on examination. | Orthostatic challenge | |

| 3. Cardiovascular Syncope | Arrhythmia

| Bradyarrhythmia:

| Family history of SCD, congenital heart disease such as channelopathy; QT-prolonging agents; palpitations; antiarrhythmic; ECG findings such as bifascicular block, AV conduction abnormality, sinoatrial block or inappropriate bradycardia, VT, WPW, LQTS, Brugada pattern, ARVC pattern, Q waves suggestive of MI. VT classically will have no prodrome | ECG, telemetry, outpatient monitoring (Holter, ILR), EP study |

Structural Cause

|

| Exertional syncope; angina; palpitations; Q wave suggestive of MI | Echo, stress test | |

| Pulmonary Vascular Cause | Pulmonary HTN, PE, dissection | Exertional syncope; dyspnea; pleuritic CP, tearing CP | Echo, ECG, diagnostic cath if indicated, CT chest if indicated |

Diagnosis

The relevant aspects of the history include the patient’s symptoms experienced prior to and following loss of consciousness, the setting in which syncope occurred, the patient’s past medical and psychiatric history, medications, and social history. Prior episodes and frequency of syncope episodes may also potentially help guide diagnosis and/or testing.

Determination if the event is truly syncope, rather than nonsyncope, can help include or exclude items within the differential diagnosis (Table 99-1). This initial evaluation incorporates a careful history of events before and after the LOC, a thorough assessment of past medical history, a complete medication and allergy review, and assessment of family history (including sudden death) and social history (Table 99-4).

|

Did the patient actually experience a sudden, transient LOC? Was there spontaneous recovery without resuscitation?

Certain historical features may point toward a nonsyncopal event (Table 99-1). History should delineate if there was actual loss of consciousness. A mechanical fall or confusion (altered consciousness) would not be termed syncope or even LOC.

If the patient did actually lose consciousness, consideration of nonsyncopal etiologies of transient LOC including intoxications, hypoglycemia, hypoxia, or severe anemia may be appropriate even though these rarely lead to LOC. These patients may have more gradual development of symptoms prior to a syncopal episode and/or delayed recovery (many minutes to hours) compared with true syncope.

When LOC was witnessed, description of tonic-clonic activity obviously points toward seizure as a nonsyncopal etiology of transient LOC; however, lay person witnesses of seizure activity may not be reliable in description. When a seizure is not witnessed, historical features that may point toward seizure as an etiology include lateral tongue biting or laceration (reasonably specific for seizure), pre-LOC aura, and bowel or bladder incontinence (the latter, a nonspecific finding that may occur in syncope as well). Prolonged recovery (more than one or a few minutes) to normal mentation is another hallmark of seizure, and differs significantly compared to true syncope.

Importantly, many patients with syncope are misdiagnosed as seizure due to misperception of witnesses or misinterpretation of body movement descriptions from bystanders. Any syncopal episode can lead to brief myoclonic activity (occurs in up to 10% of patients with vasovagal syncope and other types of syncope), and up to 1% of syncope patients can have benign brief (lasting one or a few seconds) “full body stiffening” prior to awakening. Many may misinterpret this as seizure activity (which alternately should last minutes or longer rather than seconds).

Extended duration of actual LOC is referred to as coma rather than syncope (which is transient). LOC that required resuscitation or defibrillation to return a pulse and consciousness is referred to as sudden cardiac death and not syncope.

Historical features suggesting cardiac etiologies of syncope include chest pain prior to syncope, syncope during exertion, and syncope while supine. In ventricular tachycardia, patients may present with syncope that has no prodrome. Often those patients recall no specific symptoms prior to the syncopal episode, only recall awakening, and are often injured from a fall.

Pump failure:

Is this patient having an acute MI?

Up to 10% of patients with acute myocardial infarction (MI) present with syncope. Similarly, up to 7% of patients who present with syncope and no chest pain may have ischemia as the cause of their syncopal event. Please refer to Chapter 124 on acute coronary syndromes (ACS) for relevant aspects of history and examination presentation of patients with acute MI or unstable angina. Any patient who presents with syncope who also had chest pain either before or after the syncopal episode needs to be evaluated for possible ACS with cardiac enzymes, telemetry monitoring, serial ECGs, and stress testing if indicated. In patients who have syncopebut no chest pain, four factors are predictive of ACS as the etiology of the syncope: (1) arm, neck, shoulder, and throat pain, (2) history of stable angina (provoked by exercise), (3) the presence of rales on physical examination, and (4) electrocardiographic ischemic abnormalities.

Patients without ischemic abnormalities on ECG are not at risk for an acute ischemic event compared to those with ischemic abnormalities on ECG.

Obstruction:

Is there obstruction to flow resulting in inadequate cardiac output?

Patients may have valvular, subvalvular, or vascular obstruction leading to reduced or transiently blocked cardiac output and a syncopal event. Valvular causes include aortic stenosis (AS), mitral stenosis, pulmonic stenosis (PS), or prosthetic valve malfunction. Historical features may include exertional syncope.

Subvalvular cardiac causes include hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy (HOCM) and atrial myxoma. Classic symptoms in HOCM include postexertional syncope. Vascular obstruction can occur due to pulmonary embolus (PE) or significant pulmonary hypertension. Of all patients admitted to the hospital with syncope, less than 1% are due to PE. However, despite occurring uncommonly clinicians should consider the diagnosis in patients with pleuritic chest pain, shortness of breath or symptoms to suggest lower-extremity venous thromboembolism.

Are ventricular arrhythmias suspected as the cause of syncope?

Risk factors include CAD, valvular AS, cardiomyopathy, congenital heart disease, prolonged QT interval on ECG, use of antiarrhythmic drugs especially in patients with reduced LV function, hypo- or hyperkalemia, and hypomagnesemia. History may include palpitations, chest pain, or syncope in association with exercise. However, classically patients with ventricular arrhythmia causing syncope present with no symptoms at all prior to the syncopal event, and injury can occur commonly. Syncope while supine is also concerning for possible ventricular arrhythmia. Finally, a variety of drugs may prolong the QT interval (www.qtdrugs.org), and place patients at risk for torsades de pointe.

Are supraventricular arrhythmias or bradyarrhythmias suspected as a cause of syncope?

While syncope occurs uncommonly in supraventricular tachyarrhythmias, risk factors may include prior history or risk of atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter, multifocal atrial tachycardia, and AV node reentrant tachycardia. Malignant bradyarrhythmias can lead to syncopal events, and may be due to conduction system disease, especially with AV nodal blocking agents, pacemaker malfunction, bundle branch blocks (BBB), or bifascicular block.

Is the patient having a benign vasovagal episode?

Reflex syncope, also known as vasodepressor syncope, vasovagal syncope, neurocardiogenic syncope, or the “common faint,” is the most common cause of syncope. Reflex syncope is mediated by inappropriate vasodepressor (ie, loss of vasoconstriction during standing) or cardioinhibitory (ie, reflex reaction characterized by bradycardia and/or asystole) responses to orthostatic challenge or emotional stress. It may also be precipitated by Valsalva (eg, micturition, defecation, swallowing) or mobilization after prolonged bed rest.

Diagnosis is clinical by eliciting classic symptoms. The classic prodrome, exhibited by a sympathetic response—diaphoresis, palpitations/tachycardia, piloerection, anxiety, pallor—followed by a parasympathetic response—nausea and/or vomiting, warmth/venodilation, low heart rate—can help correctly diagnose the condition. Obviously, individual patients may exhibit only a portion of the classic symptoms.

In reflex syncope related to carotid sinus hypersensitivity, classically there is no mechanical trigger leading to syncope, and it should be diagnosed by provocation through carotid sinus massage. Occasionally, these patients may describe syncope after rapid head or neck movements.

Sometimes, reflex syncope can occur in response to serious vascular events, particularly subarachnoid hemorrhage or aortic dissection. In these cases, the syncope itself may be a benign reflex event, but the underlying precipitant is life threatening and must be identified through additional historical clues such as severe headache or intense chest and back pain.

Is orthostasis causing the patient’s syncope?

Syncope due to orthostatic hypotension (OH) can occur with (1) inadequate venous return (low cardiac output), (2) structural damage to the autonomic nervous system (ANS), or (3) transient impairment of normal autonomic nervous system function. The latter may occur with medications that block the normal autonomic responses of the heart (eg, beta-blockers or nonselective calcium channel blockers [CCBs]), or with medications that block the normal autonomic responses of the vasculature (eg, peripherally-acting CCBs or alpha-blockers).

Inadequate venous return may be caused by volume depletion due to inadequate intake or excess losses through the gastrointestinal track, kidneys, or insensible losses (skin, lungs). Low venous return due to venous pooling can occur within the splanchnic system following a meal or in the peripheral venous system (eg, venous insufficiency).

Low peripheral resistance can result from primary or secondary autonomic nervous system (ANS) failure (Figure 99-2). With an intact ANS, drug-induced ANS failure or inappropriate vasodepression during a reflex response can cause syncope. These etiologies can be categorized as syncope due to orthostatic intolerance or orthostatic hypotension (OH). Vasovagal syncope occurs when the initial adaptation reflex is appropriate with orthostatic challenge, but eventually venous return falls and there is an inappropriate cardioinhibitory response, leading to bradycardia (and low cardiac output) while blood pressure (peripheral vascular resistance) is already low.

Finally, postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) is a poorly understood entity believed to occur due to autonomic dysfunction that can be exacerbated by deconditioning. It is manifested by a pathologic excess of venous pooling, early palpitations (in which HR increases by 30 bpm, or up to 120 bpm with standing) and BP instability in response to the venous pooling. It may be associated with chronic fatigue syndrome.

In the elderly, in addition to drug-induced OH, there are two predominant forms of OH: classical OH and delayed OH. In classical OH, chronic ANS failure impairs sympathetic vasoconstriction leading to low systemic vascular resistance in an orthostatic challenge. systemic vascular resistance (SVR) in an orthostatic challenge. In delayed OH, a decline in venous return is coupled with inappropriately low CO and impaired vasoconstriction, leading to syncope.

Initial physical examination should focus on vital signs, including orthostatic assessment and thorough cardiac and neurologic evaluations. At least two retrospective studies (including more than 2700 patients) have shown that orthostatic evaluation is documented in less than 40% of patients admitted to the hospital with syncope. The orthostatic evaluation is a critical piece of information (irrespective of having received intravenous fluids in the emergency department), and should always include heart rate in addition to pulse. Supine parameters should be obtained after the patient has been resting quietly for a few minutes, followed by having the patient stand upright if possible. Obtain and record blood pressure immediately upon standing, then repeat the process in the next two to three minutes, with a pulse rate obtained at the end of the standing period. Cardiac examination should include inspection, evaluation of arterial and venous pulsations and bruits (especially carotid auscultation), and cardiac palpation and auscultation. Evaluation for rales, jugular venous distention, any displacement of the apical impulse, and S3 can aid in the diagnosis. A neurologic examination should include level of consciousness and orientation, cranial nerves, motor, sensory, cerebellar, and gait evaluations.

Clinical Diagnosis and Risk Stratification: ECG and Other Testing

Key historical features and physical examination should guide appropriate diagnostic direction (Table 99-4). The history and physical examination aid with rapid recognition of life-threatening etiologies and are critical for clinicians to make appropriate decisions regarding discharge versus further triage and management.

The ECG plays a critical role in the initial evaluation, risk stratification, and treatment course related to a syncopal event. An ECG should be obtained in all patients who present to the ED, clinic, or hospital following a syncopal episode. The ECG is abnormal in 50% of patients who present with syncope. However, the ECG is diagnostic in only approximately 5% of patients. An ECG can reveal ischemia, rhythm abnormalities, atrioventricular (AV) conduction abnormalities, preexcitation (Wolff-Parkinson-White, WPW), Brugada pattern (ST elevation in V1-V3 with right bundle branch pattern), long QT syndrome (LQTS), and arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (V1-V2 negative T waves, epsilon waves, and delayed ventricular potential, ARVC). Please refer to the chapters on supraventricular tachyarrhythmias, Chapter 126, and ventricular arrhythmias, Chapter 128, for more information.

Findings considered diagnostic

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree