Symptomatology of Migraines without Aura

Alessandro S. Zagami

Anish Bahra

DEFINITION

IHS ICHD-II Code and Diagnosis

1.1 Migraine without aura

WHO ICD-10NA Code and Diagnosis

G43.0. Migraine without aura

Short Description (Headache Classification Subcommittee, 2004) (26)

Recurrent headache disorder manifesting in attacks lasting 4 to 72 hours. Typical characteristics of the headache are unilateral location, pulsating quality, moderate or severe intensity, aggravation by routine physical activity, and association with nausea and/or photophobia and phonophobia.

Previously Used Terms

Common migraine, hemicrania simplex

IHS Diagnostic Criteria for Migraine Without Aura (Headache Classification Subcommittee 2004)

A. At least five attacks fulfilling B through D

B. Headache attacks lasting 4 to 72 hours (untreated or unsuccessfully treated)

C. Headache has at least two of the following characteristics:

1. Unilateral location

2. Pulsating quality

3. Moderate or severe pain intensity

4. Aggravation by or causing avoidance of routine physical activity (e.g., walking or climbing stairs)

D. During headache at least one of the following:

1. Nausea and/or vomiting

2. Photophobia and phonophobia

E. Not attributed to another disorder

INTRODUCTION

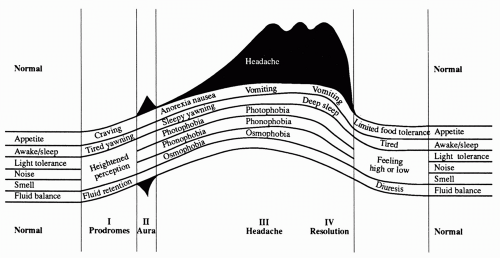

Migraine without aura is the commonest form of migraine (46). It has been suggested (6) that the migraine episode be divided into five distinct phases: (a) premonitory symptoms, (b) aura, (c) headache and associated symptoms, (d) resolution, and (e) recovery (Fig. 43-1). In migraine without aura headache is an essential part of the diagnosis and, although not preceded by any identifiable focal symptoms of neurologic disturbance, as is the case in migraine with aura, it may be preceded by premonitory symptoms, often quite characteristic for the individual and clearly identifiable as the warning symptoms of an impending attack.

PREMONITORY SYMPTOMS

The Headache Classification Subcommittee (26) states that premonitory symptoms occur a couple of 2 days to a couple of hours before a migraine attack. They include various combinations of fatigue, difficulty in concentrating, neck stiffness, sensitivity to light or sound, nausea, blurred vision, yawning, and pallor. Premonitory symptoms have been known to precede a migraine attack for centuries (28) and have been classified on clinical grounds as excitatory or inhibitory (5). Excitatory premonitory symptoms include irritability, being “high,” physical

hyperactivity, being obsessional and witty, yawning, excessive sleepiness, increased sensitivity to light and sounds, craving for food, increased bowel and bladder activity, and thirst. Inhibitory symptoms include being withdrawn, mental slow down, behavioral sluggishness, feeling tired, difficulty focusing, slurred speech, difficulty finding the right word, poor concentration, slow thinking, asthenia, feelings of cold, anorexia, constipation, and abdominal bloating. In a study by Waelkens (64), such premonitory symptoms were classified under the headings of (a) general complaints, (b) symptoms related to the head, (c) abnormalities of eyes or sight, (d) sensory intolerance, (e) mood and behavior variations, and (f) abdominal symptoms. Children tend to have more abdominal symptoms, particularly pain as well as attacks of vertigo preceding their migraine headache without aura (43). In the various series reported so far (6,28,49,54,64,65) the incidence of premonitory symptoms has varied widely, from 7 to 88%.

hyperactivity, being obsessional and witty, yawning, excessive sleepiness, increased sensitivity to light and sounds, craving for food, increased bowel and bladder activity, and thirst. Inhibitory symptoms include being withdrawn, mental slow down, behavioral sluggishness, feeling tired, difficulty focusing, slurred speech, difficulty finding the right word, poor concentration, slow thinking, asthenia, feelings of cold, anorexia, constipation, and abdominal bloating. In a study by Waelkens (64), such premonitory symptoms were classified under the headings of (a) general complaints, (b) symptoms related to the head, (c) abnormalities of eyes or sight, (d) sensory intolerance, (e) mood and behavior variations, and (f) abdominal symptoms. Children tend to have more abdominal symptoms, particularly pain as well as attacks of vertigo preceding their migraine headache without aura (43). In the various series reported so far (6,28,49,54,64,65) the incidence of premonitory symptoms has varied widely, from 7 to 88%.

FIGURE 43-1. Symptoms and signs during phases of a migraine attack. From Blau JN. Migraine: theories of pathogenesis. Lancet. 1992;339:1202-1207, with permission. |

Early studies of premonitory symptoms, however, lacked scientific rigor. In a recent study (23) of a selected patient population, the majority of whom had migraine without aura, prospective electronic diary documentation showed that tiredness (72%), difficulty with concentration (51%), and a stiff neck (50%) were the most common premonitory symptoms reported. The most reliable predictors, however, were yawning, difficulties with speech, difficulties with reading, and increased emotionality. Premonitory symptoms accurately predicted the onset of migraine headache within 72 hours 72% of the time.

TRIGGER FACTORS

Triggers (also called precipitating factors) are factors that, alone or in combination, induce headache attacks in susceptible individuals. Trigger factors precede the attack usually by less than 48 hours. This distinguishes them from aggravating factors. Triggers induce headache attacks in predisposed subjects and are not regarded as causal agents. Triggers are not universal. Moreover, the presence of a trigger factor does not always precipitate an attack in the same individual. This suggests a multifactorial trigger mechanism for individual attacks. One or more precipitating factors have been described in between 64 and 90% of patients with migraine (45,49,54,62), and overall they appear to be more common in patients with migraine without aura than in those with migraine with aura (49). The nature and frequency of the commonest precipitants are listed in Table 43-1.

Stress

Studies have consistently reported that stress and “mental tension” are the most common provoking factors for migraine (45,49,51,54,56,62). It should be borne in mind

that in some patients “mental tension” may be a prodromal symptom (62).

that in some patients “mental tension” may be a prodromal symptom (62).

TABLE 43-1 Frequency of Precipitating Factors in Migraine (%) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Dietary Factors

Many patients identify dietary factors as triggers for migraine. Between 20 and 52% of patients report that alcoholic drinks can precipitate their attacks (39,40,45,49,62). Whereas some patients are sensitive to all forms of alcohol, a smaller number report sensitivity only to red wine or, less commonly, beer (39).

Certain foods have been implicated as triggers by between 10 and 45% of migraineurs (39,40,45,49,51, 54,56,62). The most common foods reported are chocolate, dairy food (in particular cheese), citrus fruit, and fried fatty foods. In one retrospective study (40), only about 19% of migraineurs claimed to be sensitive to cheese or chocolate or both, and 11% to citrus fruit. Most diet-sensitive patients were sensitive to all three foods. Interestingly, two double-blind placebo-controlled trials testing whether chocolate was a trigger for migraine came to opposite conclusions (22,35).

Menstruation

Menstruation is cited by women as a precipitant for migraine with a frequency of between 24 and 62% (45,49, 51,56,62) and appears to be more frequent in migraine without aura (49,54). It should be remembered that hormonal factors may act both as aggravating as well as precipitating factors. This is discussed in more detail in Chapter 35.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree