Symptomatology of Cluster Headaches

David F. Black

Carlos A. Bordini

David Russell

DEFINITION OF CLUSTER HEADACHE

IHS Code and Diagnosis

3.1 Cluster headache

3.1.1. Episodic cluster headache

3.1.2. Chronic cluster headache

WHO Code and Diagnosis

G44.0 Cluster headache syndrome

Short Description

According to the International Classification of Headache Disorders II (ICHD-II) (22), cluster headaches are attacks of severe, strictly unilateral pain that is orbital, supraorbital, temporal, or any combination of these sites lasting 15 to 180 minutes and occurring from once every other day to eight times a day. The attacks are associated with one or more of the following, all of which are ipsilateral: conjunctival injection, lacrimation, nasal congestion, rhinorrhea, forehead and facial sweating, miosis, ptosis, and eyelid edema. Most patients are restless or agitated during an attack.

Attacks occur in series lasting for weeks or months (cluster periods) separated by remission periods, usually lasting months or years. Cluster headache is most often episodic, but about 10 to 15% of cases are chronic wherein patients suffer attacks recurrently for at least a year with remissions lasting less than 1 month (14). The symptomatology of the chronic and episodic form is otherwise almost identical.

Previously Used Terms

Erythroprosopalgia of Bing

Ciliary or migrainous neuralgia (of Harris)

Erythromelalgia of the head

Horton headache

Histaminic cephalalgia

Petrosal neuralgia (of Gardner)

Sphenopalatine

Vidian and Sluder neuralgia

Hemicrania periodica neuralgiformis

The IHS diagnostic criteria for cluster headache according to ICHD-II are as follows (22):

A. At least five attacks fulfilling B through D.

B. Severe or very severe unilateral orbital, supraorbital, and/or temporal pain lasting 15 to 180 minutes if untreated.

C. Headache is accompanied by at least one of the following:

1. ipsilateral conjunctival injection and/or lacrimation;

2. ipsilateral nasal congestion and/or rhinorrhea;

3. ipsilateral eyelid edema;

4. ipsilateral forehead and facial sweating;

5. ipsilateral miosis and/or ptosis; or

6. a sense of restlessness or agitation.

D. Attacks have a frequency from one every other day to eight per day.

E. Not attributed to another disorder.

PREMONITORY SYMPTOMS

Nonpainful symptoms may occur minutes to weeks before the pain of a cluster headache. Some authors refer to the symptoms occurring days to weeks before a cluster period as premonitory and symptoms occurring minutes to hours before an individual attack prodromal (5,48). These symptoms may include lethargy, elation, irritability, paresthesia, nausea, and strange sensations throughout the body. Patients also may experience sensations in the area of subsequent pain, including awareness, twinges, pressure, tingling, or pulsations (5). The line between prodrome and premonitory can be indistinct and

the ICHD-II has discouraged the use of prodrome to avoid confusion.

the ICHD-II has discouraged the use of prodrome to avoid confusion.

CHARACTERISTICS OF INDIVIDUAL ATTACKS

Cluster headache attacks include recurrent bouts of extremely severe pain in association with prominent signs of cranial autonomic activation, both of which typically occur in a cyclical, or periodic, fashion. Wilfred Harris’ and Bayard Horton’s observations from 1926 and 1939, respectively were key in making the clinical phenotype known to the medical world (21,25).

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS OF PAIN

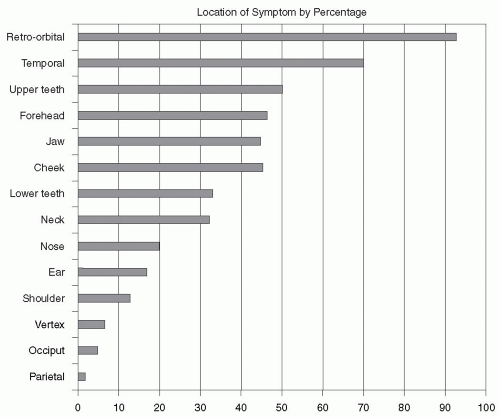

In the majority of cases, pain starts in the retro-orbital, supraorbital, or temporal regions, but it may radiate to the forehead, upper or lower jaw, nostril, ear, half of the head, and, in some cases, the ipsilateral neck or shoulder (Fig. 92-1. Attacks of infraorbital as opposed to only supraorbital pain are sometimes distinguished as lower and upper cluster headache with higher propensity for autonomic symptoms in the former (6). In the great majority of patients, the pain of cluster headache always affects the same side of the head; however, up to 14% of patients may experience a side shift with the pain during a cluster period, whereas 18% may have side shifts from one cluster period to the next (3). During attacks and more rarely between attacks, patients may be supersensitive to touch in the symptomatic area.

FIGURE 92-1. Location of pain during cluster headache attacks by percentage (N = 230 patients). Adapted from Bahra et al. (3). Retro-orbital 92; Temporal 70; Upper Teeth 50; Forehead 46; Jaw 45; Cheek 45; Lower teeth 32; Neck 31; Nose 20; Ear 17; Shoulder 13; Vertex 7; Occiput 6; Parietal 1. |

The attack often begins as a vague discomfort and rapidly increases to excruciating pain, reaching maximal intensity within 9 minutes of onset in 86% of sufferers (66). Cluster headache has often been described as the most painful primary headache syndrome. Patients have been known to commit suicide during attacks, justifying the moniker of “suicide headache.” The quality of pain is constant, boring, pressing, or burning when reaching its peak. At times subjects report a feeling of a “hot poker” in the eye or an extremely severe pressure within or behind the eye. A minority (30%) describe the pain as throbbing or pulsating. However, sometimes it cannot be described or classified, and in some other cases it may have a mixed

quality (throbbing and “neuralgic”). Sudden jabs of intense pain lasting 1 to 2 seconds also may be experienced in the symptomatic area during the attack.

quality (throbbing and “neuralgic”). Sudden jabs of intense pain lasting 1 to 2 seconds also may be experienced in the symptomatic area during the attack.

The severity of attacks usually increases (together with the frequency) in the first few days or weeks and is most severe in the middle phase of the cluster period, but even then patients may occasionally experience milder attacks (52). In some patients a slight discomfort or ache persists in the symptomatic area between attacks.

AUTONOMIC FEATURES

During cluster headache attacks, subjects may experience either local or systemic features of autonomic nervous system activation to a degree commensurate with the severity of the pain. Among the local signs of autonomic involvement, lacrimation is the most common, being reported in 82 to 91% of cases, followed by ipsilateral injection of the conjunctiva (58 to 84%). A partial Horner syndrome, with a slight ipsilateral ptosis or miosis, and/or eyelid edema is often present during attacks (57 to 69%) and may persist between attacks in later stages of the disease in some patients. Nasal stuffiness or rhinorrhea experienced by most patients during attacks (68 to 76%) is usually ipsilateral to the headache, but rarely may be bilateral. Nasal stuffiness in some cases may precede the onset of pain, later in the attack being replaced by rhinorrhea (53). Increased forehead sweating can be measured during severe attacks, especially on the symptomatic side. This sign can be clinically observed, however, in only a minority of patients (62). A few patients report generalized sweating during attacks. Cardiovascular findings accompanying cluster attacks include the following heart rate changes: increase in heart rate at the onset of attacks, decrease in heart rate after attacks, and rhythm disturbances (54). These consist of frequent premature ventricular beats, transient episodes of atrial fibrillation, and first-degree atrioventricular block or sinoatrial block. Moreover, both diastolic and systolic blood pressures may be increased (55). Gastrointestinal symptoms are not typical of cluster headache attacks.

In a large series of consecutive patients, Ekbom (13) found that in 3% of cases the diagnostic criteria were not fulfilled because of the absence of local autonomic signs during cluster attacks. In the series described by Nappi et al. (46), 3% never experienced autonomic symptoms during cluster headache, although these attacks were not personally observed. It may be assumed that the impairment of autonomic functions in these cases was present to a mild degree that was not clinically manifest but would have required advanced laboratory studies for sheer detection. Conversely, patients may, either spontaneously or after trigeminal nerve sectioning, endure periodic attacks of autonomic symptoms resembling cluster headache without the pain (35,36).

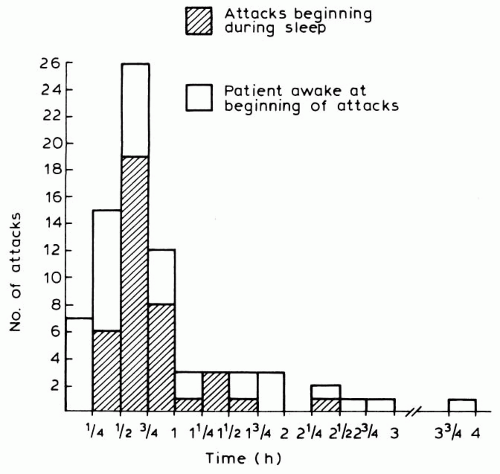

FIGURE 92-2. Duration of cluster headache attacks. Reproduced from Russell (52). |

DURATION AND FREQUENCY OF INDIVIDUAL ATTACKS

Attacks typically last between 15 minutes and 3 hours, generally being shorter at the beginning and end of each cluster period. In a prospective study of 77 attacks (52), total duration was less than 30 minutes in 29%, less than 45 minutes in 62%, and less than 1 hour in 78% of patients (Fig. 92-2. A different prospective study of 230 patients found an average minimum attack duration of 72 minutes versus an average maximum duration of 159 minutes (3). The severity and duration of nocturnal and daytime attacks are similar.

The attack frequency is usually one or two per 24 hours, although the IHS diagnostic criteria suggest a minimum of one attack every other day and a maximum of eight per day. It is noteworthy that, in the evaluation of the outcome of the disease made by Manzoni et al. (40), the frequency of attacks showed a dichotomous evolution in primary episodic and primary chronic cluster headache patients. In the former condition, the attacks tended to increase in frequency, whereas in the latter they tended to decrease during the course of the disease. The duration of each attack tended to lengthen in all groups.

BEHAVIOR DURING AN ATTACK

The typical patient behavior has been described in detail (4) and has been incorporated into the ICHD-II diagnostic criteria. Subjects prefer to isolate themselves; they appear

agitated, restless, and feel an impulse to move around or go outside in an attempt to cope with the torment of excruciating pain (66). Subjects may rub or compress their head, pace, apply cold substances to the site of pain, or seek a dark room. The awareness of these typical patterns of walking, sitting, kneeling, lying, and standing during attacks helps the patient to realize that bizarre behavioral responses are not the mark of insanity. Violent behavior is rare, but subjects may strike their heads on the wall or with their hands. This behavior appears depend on the severity of the pain during attacks (52).

agitated, restless, and feel an impulse to move around or go outside in an attempt to cope with the torment of excruciating pain (66). Subjects may rub or compress their head, pace, apply cold substances to the site of pain, or seek a dark room. The awareness of these typical patterns of walking, sitting, kneeling, lying, and standing during attacks helps the patient to realize that bizarre behavioral responses are not the mark of insanity. Violent behavior is rare, but subjects may strike their heads on the wall or with their hands. This behavior appears depend on the severity of the pain during attacks (52).

ACTIVE PHASES AND REMISSIONS

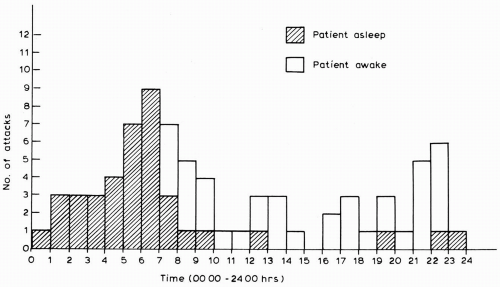

Periodicity is the hallmark of cluster headache. Episodic cluster headache often manifests with both a circadian (certain times of day) and circannual (certain seasons of the year) periodicity. Various attack patterns have been documented with peaks around 1 to 2 AM, 1 to 3 PM, and 9 PM (41).

Circadian Periodicity

In Russell’s study (52), 51% of attacks began when patients were asleep, the peak frequency being from 4 AM to 10 AM (Fig. 92-3. The average time asleep per 24 hours for patients during the study did not exceed 6.9 hours, so that the relative frequency of attacks was increased during sleep. There is also a tendency for daytime attacks to begin during naps or periods of physical activity.

FIGURE 92-3. Time of onset of cluster headache attacks. Reproduced from Russell (52). |

Cluster headache patients often develop attacks about 90 minutes after going to sleep, indicating a relationship with REM phase sleep (42). Nocturnal attacks can occur during periods of oxygen desaturation with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) associated with REM sleep and 31 to 80% of cluster headache sufferers may have evidence of OSA during polysomnography (18,47).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree