Key Clinical Questions

How do stupor, coma, persistent vegetative state, minimally conscious state, and akinetic mutism differ?

What historical features and examination findings are useful in the diagnosis of acute stupor and coma?

How is acute coma in hospitalized patients managed?

What prognostic information should be given to surrogate decision makers for patients with severe alterations of consciousness?

Introduction

Alterations of consciousness are frequently encountered by hospitalists in the practice of general medicine. Coma is an unconscious brain state produced by several acute or chronic brain insults. The acute onset of coma is a medical emergency and requires immediate assessment and specific therapy. Coma is distinct from vegetative state, minimally conscious state, and akinetic mutism, conditions that are sometimes confused with it. The timing and probability of recovery from coma and the vegetative state differ considerably, depending on the nature of the underlying brain injury. We review diagnosis and prognosis in disorders of consciousness, address ethical challenges arising in the care of these patients, and provide a guide to discussions with surrogate decision makers for the comatose or severely brain-injured patient.

Coma and Related Disorders of Consciousness

Lethargy refers to a minor decrease in alertness and energy, whereas obtundation refers to a moderate decline in responsiveness. Stupor is applied to patients with marked impairment of arousal who nevertheless sometimes respond purposefully to vigorous physical stimuli, such as prodding, sticking with a pin, or calling out loudly. Stupor resembles deep sleep.

Coma is a brain state characterized by the total absence of patterned behavioral arousal. Comatose patients are completely unresponsive. Like stuporous patients, they appear to be in deep sleep, lying motionless with eyes closed, but without eye opening or purposeful movements induced by vigorous stimulation. Coma is produced by a variety of acute or chronic brain insults. It may be distinguished from syncope, concussion, or other forms of transient unconsciousness by its time course. The term coma implies duration of at least 1 hour. Although some comatose patients recover rapidly, especially when coma is due to a concurrent systemic illness, a more gradual recovery is often seen for patients with brain injuries sufficient to produce even a day of coma. In such patients, recovery will be marked by the patient’s entering into a vegetative state or minimally conscious state, as defined below.

Although coma patients lack purposeful responses to internal or external stimuli, noxious stimuli may cause them to grimace or make stereotyped withdrawal movements of the limbs generated by spinal reflexes. These movements are not directed toward the external stimuli and are not organized actions consistent with purposeful avoidance. In very deep coma, even these primitive reflex responses may disappear.

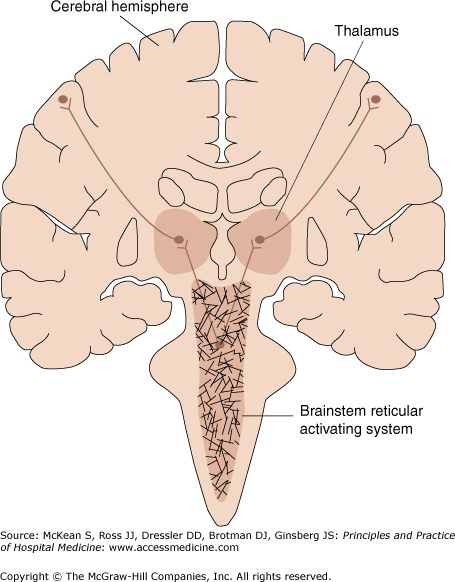

In coma, normal brain arousal mechanisms that control the level of neuronal activity in the brain and the normal sleep–wake cycle are disrupted. Coma requires disruption of either bilateral hemispheric functioning or the brainstem reticular activating system (Figure 208-1). Causes of coma include metabolic disturbances, such as anoxia, acidosis, and hyponatremia, drug intoxication, severe bilateral injuries to the cerebral hemispheres, and injuries to a small set of regions of the upper brainstem or thalamus resulting from stroke or herniation syndromes (Table 208-1).

Figure 208-1

Anatomical basis of coma. Consciousness is maintained by the normal functioning of the brainstem reticular activating system above the midpons and its bilateral projections to the thalamus and cerebral hemispheres. Coma results from lesions that affect either the reticular activating system or both hemispheres. (Reproduced, with permission, from Simon RP, Greenberg DA, Aminoff MJ. Clinical Neurology. 7th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2009. Fig. 10-1.)

|

Clustered within the brainstem and basal forebrain are several neuronal populations that support wakefulness. These include glutamatergic and cholinergic neurons in the brainstem and basal forebrain, serotoninergic and noradrenergic neurons of the brainstem, and histaminergic and orexin-producing neurons of the hypothalamus. Because arousal is controlled by multiple systems, relatively large bilateral injuries to the upper pons, midbrain, or central thalamus are needed to produce coma in humans. Coma arising from such focal injuries is short-lived, typically lasting only hours or a few days, and is unlikely to be encountered by the hospitalist.

Following a coma produced by severe brain injury, patients may either deteriorate, with progressive neuronal damage leading to brain death, or show signs of recovery, heralded by brief periods of eye opening without behavioral responsiveness. Comas that do not resolve quickly instead evolve into the vegetative state, minimally conscious state, and other related clinical syndromes.

In the persistent vegetative state, there is a limited recovery of arousal, with spontaneous periods of eye opening, reflecting some functional recovery of the brainstem and reticular activating system, but without evidence of awareness of self or the environment. The vegetative state frequently arises following coma, and the structural injuries producing the vegetative state strongly overlap with those that produce coma. Common causes include diffuse axonal injury from brain trauma and anoxic brain injury from cardiac arrest. Autopsies of patients in the persistent vegetative state typically show widespread disconnection of the corticothalamic system, with extensive death of thalamic neurons. Within the thalamus, the central thalamic neurons show the greatest volume loss; bilateral damage to these regions in isolation can produce coma.

The minimally conscious state is differentiated from the vegetative state by inconsistent but unequivocal evidence of awareness of self or the environment. A range of subtle behaviors may indicate responsiveness in the minimally conscious state. For example, a patient might be limited to tracking of objects in the visual field or localization of auditory stimuli, such as head turning to a ringing bell. Because these behaviors may be manifested only intermittently, the patient must be assessed over multiple examinations.

Alternatively, some minimally conscious patients may have high-level responses, such as intermittent verbalization and communication. Although the bedside distinctions between the vegetative and minimally conscious states may be subtle, pathologic studies suggest that there are major differences in underlying structural pathology. Some patients in the minimally conscious state have no evidence of thalamic injury or severe diffuse axonal injury, patterns that are never seen in the vegetative state. This suggests a different anatomical substrate for residual cerebral function in many patients in the minimally conscious state. It is likely that substantial portions of the corticothalamic system are preserved in patients with the minimally conscious state, in contrast to those in the vegetative state.

Akinetic mutism is a somewhat ambiguous term. In general, it refers to conditions consistent with the minimally conscious state or a higher level of recovery. Akinetic mute patients show apparent attentiveness and vigilance, as often evidenced by deliberate visual tracking of the examiner around the room, but exhibit a paucity of behaviors, even when vigorously prompted. More specifically, akinetic mutism is a syndrome associated with bilateral damage to the anterior medial regions of the cerebral cortex, often arising from rupture of an aneurysm at the junction of the anterior cerebral arteries. These medial frontal cortical regions are closely linked and are also associated with the central thalamus and basal ganglia. Patients suffer from severe memory loss, markedly slowed behavioral responses, and an apathetic, listless appearance.

Akinetic mutism may be confused with locked-in syndrome, which results from lesions ventral to the reticular activating system in the midpons. Patients are conscious but mute and quadriplegic. They usually retain control over eye opening, vertical eye movements, and ocular convergence. Causes include pontine hemorrhage, central pontine myelolysis, tumor, and encephalitis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree