13

Stress and stress management

Introduction

Emergency nursing is generally regarded as stressful. Scenarios that confront emergency staff include patients in severe pain, unpredictability of presentations, trauma victims, dying patients and physically demanding work (Curtis 2001, Cameron et al. 2009). The International Council of Nurses (2000) recognizes the emotional, social, psychological and spiritual challenges that nurses engage within such complex environments. This chapter will provide an understanding of stress and stress management that may assist the Emergency Department (ED) nurse to cope in a busy and sometimes chaotic environment. Highlighted topics are stress and coping theories, including stressors specific to ED nursing. Contemporary issues contributing to stress take account of workload, nursing shortage, overcrowding, delayed discharge, patient expectations and violence. Crucial to this subject is an overview of stress management strategies that includes demobilizing, defusing and debriefing along with emphasis on care and support for ED nurses.

Stress theory

Multiple theories exist on stress and coping in application to physical, cognitive, emotional and behavioural characteristics. Selye (1976) defined stress as the physical body’s non-specific response to any demand made on it. The stress response is elicited when an individual perceives a threat to their self, whether real or imagined. Cognitive appraisal of a stressor determines mental as well as physical aspects of emotion. The sympathetic nervous system activates the release of adrenaline (epinephrine) and then synthesizes and secretes corticosteroids. The distribution of cortisol into the circulatory system causes raised blood glucose levels, increased heart rate, blood pressure, respirations, peripheral constriction, dilated pupils and a state of arousal or mental alertness (Tortora & Derrickson 2009).

This is what Cannon (1935) called the ‘flight-or-fight response’, describing an inbuilt mechanism that enabled our forebears to battle assailants or flee from wild animals. Matsakis (1996) has expanded this to fight, flight or freeze, explaining that contemporary stressors are different from the wild animals or battles facing earlier generations. Immobility or freezing of physical or mental capacities may occur during modern stressful situations. Exhibited behavioural responses of impaired physical or emotional function may include inadequate skills or poor communication.

Selye’s (1976) general adaptation system (GAS) is described as alarm where the body attempts to adjust; secondly, the resistance stage where the body attempts to manage the situation; and finally, the exhaustion stage where resources have been drained. Cannon (1935) examined the body’s ability to maintain and correct body systems, including regulation of temperature, nervous system, fluid–electrolyte balance and the immune response. Cannon coined the term homeostasis as the body’s attempt to re-establish equilibrium. He linked stress to be a cause of disease, explaining that the fight response is the body’s attempt towards restoration. When the body faces continued stress, illness can occur. Selye (1976) asserted that if illness were a consequence of being dis at ease, then it would be prudent to utilize preventive measures rather than temporarily patch up or mask disease states.

Exposure to stress is more commonly evidenced by the first and second stages. Selye explained that through recurring experiences individuals learn to adapt and return to a state of homeostasis. He maintained that the ability to adapt to stressful situations and regain homeostasis was an exceptional attribute of humans. The body’s attempt to re-establish homeostasis via a higher or lowered level of physiological function has been more recently identified by McEwen (2007) as allostasis. However, a continued period of physiological adaptation due to exposure to chronic stress is problematic. McEwen refers to allostatic loading as an exacerbation of the ‘flight-or-fight’ response to stress. The ED nurse who experiences chronic stress may adapt over time to wear and tear on the body and perform with a physiological adjusted ‘allostatic load’. However, adverse manifestations of excess allostatic loading include disease states such as hypertension, neurological or immune dysfunctions. Less commonly, a severe threat or continued demand on individual adaptation resources including allostasis may result in the third and most damaging stage of the GAS, which is exhaustion.

Coping

In general terms coping refers to the processes or skills used to deal with situations that are out of the ordinary. Some authorities identify coping more readily in the context of crisis or in adjustment to adverse conditions. Wolfe (1950) referred to stress as a process of altered internal dynamics of an individual caused by interaction with external energy from the environment. The person’s internal response as they interacted with the environmental pressure was considered by Wolfe to be influenced by prior experiences.

Lazarus’s (1966) work developed a three-phase approach to stress theory that involved a cognitive process of appraisal, coping and outcome. Primary appraisal consists of the initial evaluation of the stressor and the extent to which the threat is considered to be hazardous. Secondary appraisal considers the availability of coping strategies or resources. Lazarus describes stress as disruption of meaning, while coping is defined as the way in which an individual deals with the disruption resulting in the third phase which may be a positive or negative outcome.

Subsequently, Lazarus & Folkman (1984) differentiated ways of coping as strategies that are both behavioural and psychological. Efforts to reduce a stressful situation involve problem-focused coping or emotion-focused coping. A problem-focused coping method would be to confront or retreat from the perceived threat. While the psychological or emotion-focused approach would be to reduce stress by reframing the individual’s view and response to the stressor. Lazarus & Folkman state that the value of either mechanism determines the effect of the stressor on the individual. It is individual style that dictates the strategy applied. Vernarec (2001) adds that factors influencing the stress response consist not only of individual interpretation of the stressor, but also of the amount of perceptible support and a person’s overall health. It is unimportant whether the final outcome is helpful or unhelpful, only that the effort of coping has occurred (Lazarus & Folkman 1984).

Stress and distress

It is likely that all nurses experience stress in some form, even those who will not admit it. Workplace stress and its effects on job performance are major concerns from both a human and economic perspective (Noblet & LaMontagne 2006, Bright & Crocket 2011). Selye (1976) described eustress as good stress that motivates people to go to work, while distress is the bad stress that can create anxiety and illness through, for example, overwork. Aspects of emergency work necessitate that ED nurses will experience both distress and eustress. Experienced ED nurses may rely on instinct composed of a mixture of knowledge, skills and experience necessary to effectively cope with a variety of situations. Stimuli in the internal environment may arise in terms of thoughts, feelings and physical illness.

Research suggests a vulnerability to adverse effects of stress in a study of Singapore ED nurses. A study by Yang et al. (2002) found ED nurses to have lower levels of lysozome in saliva samples than general ward nurses, correlating with higher levels of perceived stress. Excessive release of glucocorticoids inhibits secretion of immunoglobin A and lysozomes, both of which affect immunity levels. This correlated with questionnaires measuring a perceived level of stress scale. Because ED nurses are exposed to significant pressures they should be aware of the signs and symptoms of increasing stress.

Signs and symptoms of stress

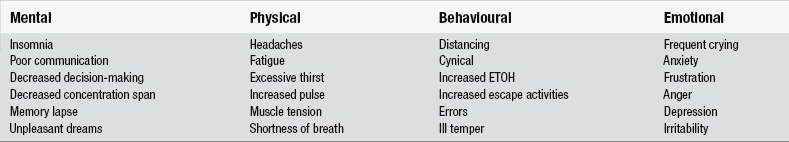

Stress may be observed in colleagues or friends before the affected nurse is actually aware. Stress can subtly influence professional and personal relationships, and is often manifested in forms of physical, emotional, behavioural and mental expression as seen in Table 13.1.

Stressors in ED nursing

For even the most competent ED nurse, continued exposure to particularly difficult and emotionally draining situations can result in crisis. Key stressors or demands identified in the literature include nursing shortage, workload, overcrowding, violence, shift work, environmental factors, communication problems and burnout (Maslasch et al. 1996). A literature review by Chang et al. (2005) identified common nursing stressors to be:

Workload and nursing shortage

Workload for ED nurses includes additional stressors, with unexpected numbers and type of patient presentations; rapidly changing status of patients; response to traumatic incidents; and patient violence (Yang et al. 2002). ED nurses have the stress of sudden and unpredictable arrivals of complex presentations without time for preparation. Increasing patient numbers and intensity increase the work of the nurse. The consequences include increased reliance on EDs and lengthening waits (National Audit Office 2004). Chang et al. (2005) blame workload underscored by work stress as the major contributor to an exodus from nursing.

Unsafe nurse:patient ratios can be accentuated in the ED where unstable patients may be vulnerable to incomplete or incompetent care (Lyneham et al. 2008). ED nurses working under pressure are at risk of compromising not only the quality of care to patients, but compromising their own job satisfaction and level of health. High ED attendance is compounded when overcrowding or bed block occurs.

Overcrowding and delayed discharge

When the number of unwell patients in an overcrowded ED exceeds the number of resources to provide competent and safe care, staff in the ED become stressed (Ardagh & Richardson 2004). Commonly thought reasons for overcrowding include an increasing ageing population, non-urgent attendees and the incline of patient admissions with existing co-morbidities. However, the chief reason for ED overcrowding appears to be a lack of hospital resourced beds (Richardson & Mountain, 2009).

Delayed discharge, also termed bed block or gridlock, refers to the unavailability of hospital beds to which ED patients would normally be transferred or admitted to (Capolingua 2008, Lyneham et al. 2008). The aging population increasingly present as high-acuity patients that negatively impacts on the ED’s maximum capacity (Cowan & Trzeciak, 2005). Despite being fully worked up and ready for admission to a ward, these patients are kept within the confines of the ED. The impact of this extra load on EDs is possibly most felt by the ED nurse (Ardagh & Richardson 2004, Cowan & Trzeciak 2005). Identified problems are not only the physical lack of space, health and safety issues, such as infection control and cluttered environment, but also the lack of privacy and dignity for patients that can contribute to moral distress for ED nurses (Kilcoyne & Dowling 2008). The astute ED nurse will focus on absolute prioritizing of key nursing cares and patient safety, yet may experience moral distress due to an inability to provide other less vital but caring tasks. An attempt to improve nursing numbers however, does not always result in a mix of equally skilled nurses.

Skill mix

Overcrowding of EDs is acknowledged by Derlet & Richards (2000) to be a critical problem accentuated not only by bed shortages but also by staffing shortages who are already dealing with increasing patient presentations and severity. Poor skill mix where staffing is supplemented with less experienced or new ED nurses impacts heavily on EDs, where senior and more experienced nurses are allocated the most complex patients as well as supervising less experienced nurses (Emergency Nurses Association 2006). Lack of experienced ED nurses and work pressure is compounded by difficulties in communicating with aggressive patients (Walsh et al. 1998). A multitude of cultural and language variations further challenge communication stressors. Iltun (2002) underlines the importance of being aware of one’s own values, cultural differences and biases in order to avoid ineffective communication. The underlying danger exists that skill mix with a low ratio of qualified nurses can impact negatively on quality of care and patient expectations.

Violence

It is common for the ED nurse to witness or be exposed to verbal or physical violence, and was found by Healy & Tyrell (2011) to be the second most common cause of stress for ED nurses and doctors. Multiple reasons exist for exacerbated stress in patients. Pain, fear, prolonged waiting and exposure to unpleasant stimuli may trigger violent outbursts in patients (Presley & Robinson 2002). Noxious smells, sights and sounds in EDs can distress patients and visitors, which may then be displaced to nurses. Possible contributors to violence must also take into account social factors, intoxicants, withdrawal, psychoses, dementias, brain injuries and seizures or post-ictal status (Bakes & Markovchick 2010). Some stressed nurses acknowledge contributing to violent reponses from mental health patients through rude or confrontational comments or behaviours (Spokes et al. 2002

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree