SPLENIC LESIONS

CASE SCENARIO

Scenario 1

Scenario 1

A 56-year-old man with a past medical history significant for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation presents to the emergency department complaining of 2 days of left upper quadrant pain that occasionally radiates to his left shoulder. He cannot recall any recent trauma, illness, or other inciting factors. On review of systems, he has had a recent history of fatigue. He is afebrile with normal vital signs. On examination, he is tender to palpation in the left upper quadrant with no appreciable splenomegaly. His white blood cell count (WBC) is 14.2 and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) is 300 U/L.

Scenario 2

Scenario 2

A 65-year-old woman with a past medical history significant for type 2 diabetes mellitus and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, for which she takes prednisone, presents to her local urgent care with a 3-day history of subjective fevers, chills, fatigue, and abdominal pain. She has had nausea but no emesis or diarrhea. Her vital signs are notable for a temperature of 101.6°F. Physical examination reveals a diffusely tender abdomen that is soft and non-distended. Her WBC is 16.4 and blood glucose level is 320.

Scenario 3

Scenario 3

A 19-year-old man with no past medical history is brought in by ambulance following a highway-speed motor vehicle collision in which he was a restrained front seat passenger. He is alert, oriented, and hemodynamically stable. Primary survey is unremarkable on arrival, and secondary survey reveals significant tenderness to palpation of the left upper quadrant. A focused assessment with sonography for trauma (FAST) examination in the trauma bay is negative for intra-peritoneal fluid, and initial laboratory evaluation is within normal limits.

INTRODUCTION

The above scenarios all describe splenic diseases encountered in acute care surgery: splenic infarction, splenic abscess, and splenic laceration. Although all three entities present with abdominal pain, the history and patient risk factors for these diagnoses differ. The following discussion aims to describe these differences and to assist in differentiating acute splenic lesions on imaging.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Splenic Infarction

Splenic Infarction

Splenic infarction rarely occurs in a previously healthy patient. The most common etiology is atrial fibrillation, with its associated thromboemboli. Other frequent comorbid conditions include hypertension, diabetes, and malignancy, as well as any hypercoagulable state.1 Patients less than 40 years of age are more likely to have an associated hematologic disorder, whereas those over 41 years of age are more likely to suffer an embolic event.2

Splenic Abscess

Splenic Abscess

Splenic abscess is a rare condition with a reported incidence of 0.1% to 0.7%, most commonly affecting patients in the fifth to seventh decades of life.3,4 The condition confers high fatality, with a reported mortality rate ranging from 40% to100%.3,4 Unlike splenic infarction, for which hypercoagulability and atrial fibrillation are causative, in splenic abscess immunosuppression is the most common risk factor. Patients with human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS), malignancy, solid organ transplantation, chronic steroid use, diabetes mellitus, and parenchymal liver disease are disproportionately affected. As the immunocompromised patient population grows and imaging techniques improve, the rate of diagnosis of splenic abscess will likely increase.

Splenic Trauma

Splenic Trauma

The spleen is the most commonly injured organ in blunt trauma in the United States. A trauma registry including over 11,000 patients with splenic injury estimated the rate of splenic injury in trauma patients to be 4.3%, with the number of blunt injuries trending upward and the number of penetrating injuries trending downward in recent years.5 In contrast with splenic abscess and infarction, splenic trauma affects the young, with approximately half of splenic ruptures occurring in patients under the age of 24, and nearly one third between the ages of 15 and 24 years. Detection of blunt splenic injury has increased over time, likely due to increased use of computed tomography (CT) scans.5

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Splenic Infarction

Splenic Infarction

The size of a splenic infarct depends on how proximally the arterial supply occludes. A large embolus can infarct the entire spleen; however, the splenic artery usually divides into 4 to 5 branches before entering the spleen, with each branch supplying a distinct segment. An embolus in any one of these branches leads to a segmental infarction.

In patients with hypercoagulable conditions, a clot may develop spontaneously in the distal or proximal vasculature with resultant occlusion. In patients with an underlying malignancy, the infarct may arise secondary to an induced hypercoagulable state.6

In patients with thromboemboli, the clot originates from a left atrial thrombus, vegetations on infected valves, or aortic atherosclerotic debris.7 Bacterial endocarditis, often developing in patients with abnormal cardiac valvular anatomy or implanted devices, is a particularly strong risk factor, as septic embolization occurs in 50% of these patients.8

Splenic Abscess

Splenic Abscess

The most common etiology of a splenic abscess is hematogenous seeding from a remote source, such as intravenous drug use, dental abscess, or endocarditis. Less commonly, direct extension of an intra-abdominal abscess or super-infection of a remnant splenic hematoma or infarct leads to an abscess. The spleen is an isolated source of infection in only 20% of cases.8

Although single organisms usually cause splenic abscesses, polymicrobial infections do occur. Enteric bacteria such as Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumonia account for nearly two thirds of splenic abscesses. Staphylococcus and Streptococcus species also contribute.8 Fungal abscesses, which occur most commonly in patients undergoing chemotherapy, rarely yield organisms on culture, and can pose a diagnostic challenge.9

Splenic Trauma

Splenic Trauma

Motor vehicle, all-terrain vehicle, and bicycle accidents inflict splenic injury most commonly.8 The velocity of impact determines injury severity. The splenic vascular pedicle and ligamentous attachments tether the spleen to the retroperitoneum, increasing its susceptibility to deceleration injury.

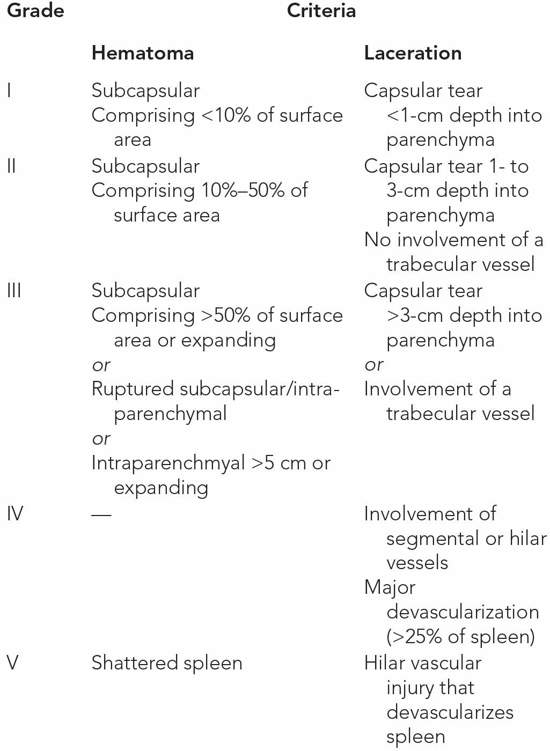

Atraumatic splenic rupture occurs infrequently compared with traumatic splenic injury. It usually arises in the setting of an enlarged spleen, with stretched and weakened parenchyma a result of an underlying hematologic, inflammatory, infectious, or neoplastic condition (Table 19–1).

Abbreviation: AAST, American Association for the Surgery of Trauma.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Splenic Infarction

Splenic Infarction

Most patients—up to 80% in one case series—with splenic infarction present with generalized abdominal pain. In the aforementioned study, pain localized to the left upper quadrant in only 33% of patients, and 16% of patients complained of pleuritic chest pain.1 Patients may have fevers, chills, or general malaise, and they frequently present in the subacute setting 4 to 7 days after the onset of symptoms. On physical examination, about one third of patients have left upper quadrant tenderness and 10% have splenomegaly.1 Vitals signs will be significant for fever and tachycardia. An irregular pulse may point to atrial fibrillation as a potential causative factor.

Splenic Abscess

Splenic Abscess

The classic “clinical triad” of splenic abscess described in the literature is fever, left upper quadrant pain, and leukocytosis.10 In a retrospective review of 75 patients treated for splenic abscess, the most common presenting symptoms were fever/chills (89%), abdominal pain (84%), and nausea/vomiting (48%).3 Fatigue and malaise are common complaints. Left upper quadrant tenderness, if present, points to a splenic etiology of the abdominal pain, but patients often lack this sign. Because signs and symptoms of splenic abscess are vague, diagnosis can be quite difficult. A high index of suspicion and swift initiation of the appropriate radiographic workup are critical to avoid the morbidity and high mortality associated with delayed diagnosis.

Splenic Trauma

Splenic Trauma

Patients typically present with left upper quadrant tenderness, specifically over the ninth through eleventh ribs.8 Tenderness generalizes as hemoperitoneum develops. In severe or untreated cases, patients develop peritonitis and shock, including tachycardia, hypotension, and an acute abdomen.

There are two named findings on clinical examination that, if present, implicate the spleen as the injured organ. A positive Kehr sign occurs when blood irritates the left hemidiaphragm. Patients placed in the Trendelenberg position will report left shoulder pain with abdominal palpation.8 A positive Ballance sign refers to a palpable mass or dullness to percussion in the left upper quadrant, representing a contained subcapsular hematoma due to splenic injury.8

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

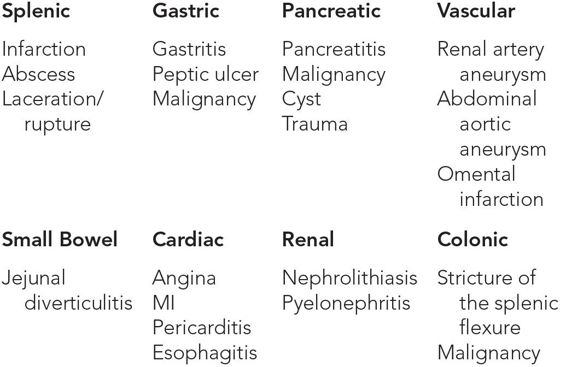

See Tables 19–2 and 19–3.

Abbreviation: MI, myocardial infarction.

WORKUP AND CHOICE OF IMAGING

Splenic Infarction

Splenic Infarction

If there is clinical suspicion for splenic infarction, a basic set of labs, including a complete blood count (CBC), electrolytes, blood cultures, and a lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level, should be drawn. Leukocytosis and positive blood cultures indicate possible infective endocarditis, and elevated LDH is present in 71% of patients with splenic infarction.6

An abdominal ultrasound is an easy first-line modality, but is highly operator dependent and limited by intraabdominal gas and body habitus. An intercostal approach is usually taken postero-laterally along the long axis of the 10th rib. Normal splenic parenchyma appears homogeneous, with reflectivity slightly lower than hepatic parenchyma.11 In one study that used both CT and ultrasound for diagnosing splenic infarcts, ultrasound was found to be diagnostic only 18% of the time.1 Ultrasound is also suboptimal for characterizing early-stage splenic infarcts because they are isoechoic with the splenic parenchyma.

A CT scan of the abdomen with intravenous contrast is the imaging modality of choice for infarct, as it is fast, sensitive, and specific. A CT scan accurately identifies splenic infarction and can reveal associated abnormalities in other organs. If infectious endocarditis is the causative factor, then additional occlusions may be noted in the hepatic or enteric vasculature.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is rarely the first choice of imaging, given the prolonged acquisition time compared with CT scan.

Splenic Abscess

Splenic Abscess

Initial workup should include a CBC, electrolytes, and blood cultures. Depending on the severity of the patient’s abdominal pain, imaging may start with a plain abdominal film, which is widely available, involves relatively low radiation exposure, and can reveal free intra-peritoneal air concerning for perforated viscus.

Ultrasound is sensitive in detecting the presence of a splenic abscess, but is nonspecific and does not provide the additional clinically relevant information, such as involvement of neighboring organs or the exact size and location of the abscess. The appearance of an abscess on ultrasound is variable, making this modality difficult for diagnostic confirmation.

As with splenic infarction, abdominal CT scan with IV contrast is the study of choice for splenic abscess, because it most accurately characterizes the number and location of abscess cavities, as well as the cavity contents. CT scan can reliably distinguish an abscess from similar-appearing disease processes, such as splenic cyst or hematoma.3

Splenic Trauma

Splenic Trauma

Evaluation of the patient with abdominal trauma begins with evaluation and support of the airway, breathing, and circulation. Laboratory studies in acute trauma are of limited diagnostic value, but lactate, hematocrit, and chemistry levels can provide helpful baselines to guide resuscitation. A portable chest film revealing left-sided rib fractures can implicate splenic injury, as can displacement or a corrugated appearance of the greater curvature of the stomach due to splenic hematoma infiltrating the gastrosplenic ligament.8

The focused assessment with sonography for trauma (FAST) examination has supplanted routine diagnostic peritoneal lavage for determination of hemoperitoneum. FAST in the hands of an experienced operator has a sensitivity of greater than 90% for detecting the presence of intraperitoneal fluid.12 The test can be quickly performed at the bedside of even the most unstable patients. Hemodynamic instability with a positive FAST examination mandates exploratory laparotomy for hemorrhage control.

In hemodynamically stable patients, a CT scan with IV contrast best evaluates for splenic injury, as it visualizes abnormalities in the splenic parenchyma as well as intraperitoneal blood. Patients with a negative FAST examination may not need a CT scan, but up to 29% of blunt trauma injuries may be missed if a FAST examination is the sole evaluation.13 Better access to CT scanners and decreased cost has increased the use of CT for diagnosing splenic injury from 59.1% in 1987 to 89.4% in 2001.14

MRI is seldom used in a trauma situation because of the long duration required for image acquisition. However, if a clinician desires follow-up of a splenic injury with cross-sectional imaging, MRI may be useful as it avoids ionizing radiation.

IMAGING FINDINGS

Ultrasound

Ultrasound

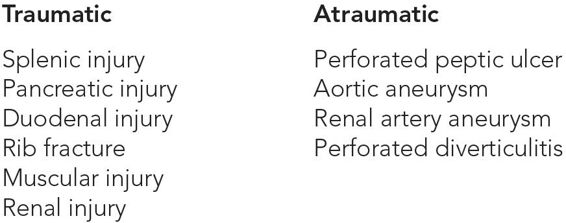

See Table 19–4.