CHAPTER 17 Spinal Manipulation and Mobilization

Description

Terminology and Subtypes

For the purpose of this chapter, spinal manipulation therapy (SMT) is defined as the application of high-velocity, low-amplitude (HVLA) manual thrusts to the spinal joints slightly beyond the passive range of joint motion.1 Spinal mobilization (MOB) is defined as the application of manual force to the spinal joints within the passive range of joint motion that does not involve a thrust.

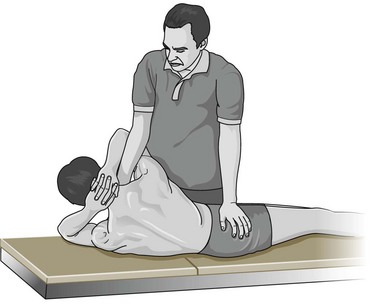

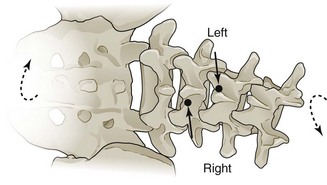

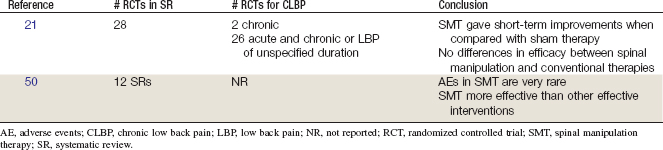

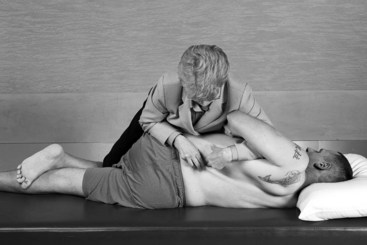

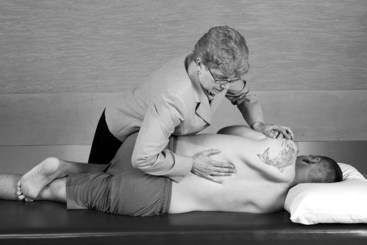

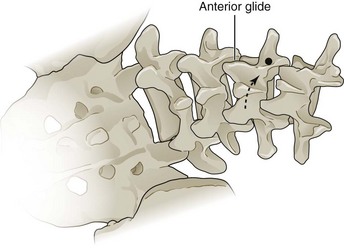

There are many subtypes of SMT currently in use, including several named technique that propose specific methods of combining patient assessment and management. The most common type of SMT technique has been termed diversified because it incorporates many of the aspects taught in these different systems. It consists of the application of HVLA thrusts to the spine with the practitioner’s hand to distract spinal zygapophyseal joints slightly beyond their passive range of joint motion into the paraphysiologic space (Figure 17-1).1 There are many specific HVLA techniques available to practitioners of SMT, which can also be modified according to patient need. This type of SMT has also been termed short-lever SMT, because the thrust is applied directly to the spine (Figure 17-2). It is distinguished from long-lever SMT, originally from the osteopathic tradition, in which force is not provided to the spine directly, but from rotation of the patient’s thigh and leg (Figure 17-3). MOB is the application of manual force to the spinal joints within the passive range of joint motion; it does not involve a thrust and may include traction through the use of specialized treatment tables. There are other types of SMT that are not covered by this review, including instrument-assisted procedures and low-force manual procedures.

Figure 17-1 Spinal manipulation therapy with distraction of zygapophyseal joints.

(Drawing from Bergmann T, Peterson DH. Chiropractic technique, ed 3. St. Louis, Mosby, 2011.)

Figure 17-2 Spinal manipulation therapy: short-lever technique with manual thrust applied by hand to the spine.

(Drawing from Bergmann T, Peterson DH. Chiropractic technique, ed 3. St. Louis, Mosby, 2011.)

History and Frequency of Use

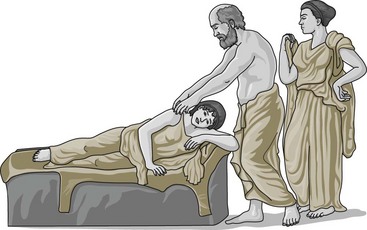

Although the practice of spinal manipulation is now frequently associated with chiropractic, which began as a profession in 1895, it predates any modern health profession and dates back thousands of years. It is believed that SMT was practiced in China as far back as 2700 bc.2 In India, SMT was historically practiced as an act of hygiene and related techniques were considered a component of surgery.2 Hippocrates, in his book On Joints, was the first to give a formal definition to the technique of manipulation; his belief in the spine as the epicenter of holistic bodily health is well known (Figure 17-4).2 As a testament to its long history of use, there are now more randomized controlled trials (RCTs) examining SMT for low back pain (LBP) than those for any other intervention.3

The use of SMT appears to be gaining popularity in recent years as increasing numbers of people with chronic low back pain (CLBP) seek complementary or alternative medicine (CAM). A survey of CAM use among the general adult population in the United States conducted in 1991 reported that chiropractic (as a proxy for SMT) had been used by 10% of respondents in the past year.4 Chiropractic was the second most commonly reported CAM therapy after relaxation techniques (13%). However, only 70% of those who reported using chiropractic had consulted with a professional health care provider; others presumably received informal chiropractic from family or friends or did not accurately report their utilization. The medical conditions for which chiropractic use was highest were back problems, arthritis, and headache. When this survey was repeated in 1997, the use of chiropractic in the previous 12 months had grown to 11% and was the fourth most common CAM therapy after relaxation (16%), herbal medicine (12%), and massage (11%).4 Among those who reported using chiropractic, the proportion who saw a professional practitioner increased to 90%. The total number of visits to chiropractic practitioners in 1997 was estimated at 192 million. The medical conditions for which chiropractic use was highest were back problems, neck problems, arthritis, headaches, and sprains or strains. A prospective study of CAM use among 1342 patients with LBP who presented to general practitioners (GP) in Germany reported that 26% received SMT in the subsequent 1 year follow-up.5 The use of SMT was statistically significantly higher among those whose GP offered SMT, with an odds ratio of 5.8 (95% CI, 3.1 to 10.0). SMT was the second most commonly reported CAM therapy after massage (31%).

Practitioner, Setting, and Availability

In most jurisdictions, SMT is considered a controlled health act and must be delivered by a licensed health care practitioner. The vast majority of SMT (previously estimated at 94%) in North America is provided by doctors of chiropractic (DCs), who receive extensive training in manual examination and manual therapies during their 4 years of education and clinical internship; licensing requirements differ considerably outside the United States.6 Some SMT is provided by doctors of osteopathy and physical therapists, who receive additional training in SMT where permitted by state licensure, and also by naturopathic doctors where permitted. SMT is most often administered in the private practice of DCs. In rare cases, SMT may occasionally be performed in conjunction with anesthesia or injections, which would require that it be performed in an outpatient surgical center. Medicine-assisted manipulation, including manipulation under anesthesia, is discussed in Chapter 18. SMT is widely available throughout the United States, with an estimated 60,000 licensed DCs practicing across the country.

Procedure

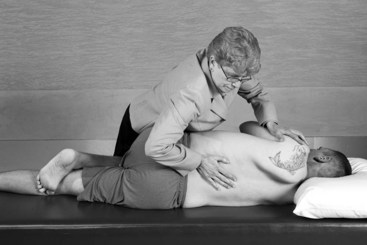

Before performing SMT, the practitioner must conduct a thorough physical examination that includes manual palpation of the lumbar and sacral areas to assess local tenderness and inflammation, and identify areas of segmental dysfunction/hypomobility to which SMT will be applied. SMT for LBP is typically performed with the patient in a side-lying position on a cushioned treatment table. The practitioner then positions the patient’s torso, hips, arms, and legs according to the desired type of SMT, places the “stabilizing” hand on the patient’s arms, and contacts the legs using the practitioner’s thigh or leg. The practitioner places the thrusting “treatment” hand over either the superior or inferior vertebra of the target spinal motion segment to which SMT will be applied. The practitioner introduces a slow force to preload the target spinal joints, and then administers an HVLA thrust with the direction, velocity, and amplitude determined by the examination and desired joint movement (Figure 17-5). The manual thrust can be assisted by a “body drop” produced when the practitioner contracts his or her abdominal and leg muscles.7 This thrust is often accompanied by an audible cracking or popping sound, which represents the formation and dissolution of small gas bubbles within the joint cavity resulting from pressure changes as the articular surfaces momentarily separate in response to the HVLA thrust.8,9

Theory

Mechanism of Action

The precise mechanism of action for many manual therapies, including SMT and MOB, is not fully understood.10 Many hypotheses have focused on singular aspects of these interventions, such as the immediate biomechanical consequences of applying an external force to the tissues of the spine. It is generally thought that if the target tissues that receive this force are relatively rigid (e.g., bone), they may displace, whereas if the target tissue are relatively pliable, they may deform. Several studies related to SMT and MOB have examined the immediate biomechanical effects of tissue displacement or deformation, including altering orientation or position of anatomic structures, unbuckling of structures, release of entrapped structures, and disruption of adhesions.11,12 Other hypotheses regarding the mechanism of action for SMT and MOB have focused on the downstream consequences of target tissue displacement or deformation, including neurologic and cellular responses.10 Evidence suggests that SMT may impact primary afferent neurons in paraspinal tissues, the motor control system, and central pain processing.13 It should be noted that such reductionistic approaches may not be appropriate to fully comprehend all the effects of a multifaceted clinical encounter that may also involve aspects such as the nonspecific effects of therapeutic touch, and potential healing effects of empathy shown by a practitioner spending time with their patient.12

Indication

Various countries and organizations have published clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) for the treatment of LBP based on systematic reviews (SRs) of evidence. In general, the recommended indication for SMT or MOB is nonspecific mechanical CLBP. Little research has been performed to evaluate which CLBP patients are best suited for SMT or MOB. Generally, SMT or MOB may be recommended for CLBP patients who do not have any contraindications. In addition, SMT or MOB may not be the best choice for patients who cannot increase activity/workplace duties, are physically deconditioned, or have psychosocial barriers to recovery.14 Recent work on acute LBP has begun to suggest characteristics to identify which patients who may respond favorably to SMT, including duration of LBP less than 16 days, symptoms that remain proximal to the knee, Fear-Avoidance Belief Questionnaire (FABQ) scores less than 19, hypomobility of the lumbar spine, and hip rotation greater than 35 degrees.15 In a study with a 6-month follow-up, when three of these five markers were present, subjects were observed to experience significantly greater benefits from SMT. More studies are needed to identify which CLBP patients are likely to benefit from SMT or MOB.

Assessment

Prior to receiving SMT or MOB, patients should first be assessed for LBP using an evidence-based and goal-oriented approach focused on the patient history and neurologic examination, as discussed in Chapter 3. Additional diagnostic imaging or specific diagnostic testing is generally not required prior to initiating these interventions for CLBP. The clinician should also inquire about general health to identify potential contraindications to these interventions.

Efficacy

Clinical Practice Guidelines

The CPG from Belgium in 2006 found moderate-quality evidence to support the efficacy of SMT when compared to no treatment with respect to short-term improvements in pain.16 That CPG also found moderate-quality evidence that SMT is not more effective than other conservative interventions including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), usual care from a GP, physical therapy (PT), exercise, or back school for CLBP.

The CPG from Europe in 2004 recommended that SMT be considered as one option for short-term improvements in pain for the management of CLBP.17

The CPG from Italy in 2007 suggested that SMT be performed only by trained clinicians after screening patients for potential risk factors such as serious spinal pathology.18

The CPG from the United Kingdom in 2009 recommended SMT as one option for the management of CLBP.19 That CPG also recommended offering a maximum of 9 sessions of SMT over a period of up to 12 weeks.

The CPG from the United States in 2007 found moderate-quality evidence to support the efficacy of SMT for the management of CLBP.20

Findings from the above CPGs are summarized in Table 17-1.

TABLE 17-1 Clinical Practice Guideline Recommendations on Spinal Manipulation Therapy or Mobilization for Chronic Low Back Pain

| Reference | Country | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|

| 16 | Belgium | Moderate evidence to support short-term efficacy |

| 17 | Europe | Recommended for short-term improvements in pain |

| 18 | Italy | Recommended spinal manipulation therapy after patient screened for potential risks |

| 19 | United Kingdom | Recommended maximum of 9 sessions over 12 weeks |

| 20 | United States | Moderate evidence to support efficacy |

| 24 | Switzerland | Unclear evidence |

| 112 | Denmark | Recommended |

| 113 | Germany | Unclear evidence |

| 114 | Sweden | Recommended |

| 25 | Finland | Unclear evidence |

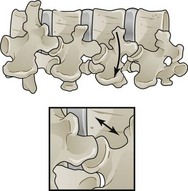

Systematic Reviews

Cochrane Collaboration

The Cochrane Collaboration conducted an SR in 2004 on SMT for LBP.21 A total of 28 RCTs were identified, 2 of which included patients with CLBP and 26 of which included both acute and chronic LBP patients or patients with back pain of an unspecified duration.22–49 Using meta-regression, the review found that compared with sham therapy, spinal manipulation gave clinical short-term improvements in pain and function for acute LBP. There was also statistically significant short-term pain improvement and clinically significant short-term improvement in function for acute LBP when SMT was compared with therapies judged to be ineffective or possibly even harmful (i.e., traction, corset, bed rest, home care, topical gel, no treatment, diathermy, minimal massage). However, there were no differences in efficacy between SMT and conventional therapies (i.e., analgesics, PT, exercises, back school) for acute LBP. There were similar findings for CLBP. This Cochrane review concluded that SMT is not superior to other standard treatments for patients with acute or chronic LBP.

American Pain Society and American College of Physicians

An SR was conducted in 2007 by the American Pain Society and American College of Physicians CPG committee on nonpharmacologic therapies for acute and chronic LBP.50 That review identified 12 SRs on SMT, including the Cochrane review described earlier and four other SRs on harms associated with SMT.3,21,51–66 The review found that five higher-quality SRs reached consistent conclusions as the Cochrane review.53,55,56,59,60 Two lower-quality SRs based on sparse data found that SMT was more effective than other effective interventions.3,58 The review also concluded that serious adverse events in SMT are very rare, based on consistent results from five SRs.59,64–67 Two other RCTs were identified by this review, which also had similar conclusions as the Cochrane review.68,69 A third other RCT was identified that evaluated a decision tool to identify patients who may benefit from spinal manipulation.15 This SR concluded that there is moderate efficacy of SMT for subacute and chronic LBP.

Findings from the aforementioned SRs are summarized in Table 17-2.

Other

A recent narrative review of SRs of RCTs on SMT by Ernst and Canter concluded that SMT is not an effective intervention given the possibility of adverse events, and suggested that SMT is not a recommended treatment.70 That review was severely limited in its approach because of an incomplete quality assessment of RCTs, lack of prespecified rules to evaluate the evidence, and several erroneous assumptions.71 For example, Ernst concluded that bias exists when SRs of SMT are performed by chiropractors (including some of the authors of this chapter). This unfounded claim was refuted and addressed by using transparency in our review, including a priori defined standards, and acceptable methods for conducting SRs.71–73 Clinicians should exercise caution when generalizing the findings of SRs to their practice. Disparate patient populations are likely to be included in SRs and potentially important distinguishing characteristics, such as condition severity, are not always carefully defined. In addition, diverse SMT and MOB therapeutic approaches are applied by providers with different backgrounds and training, which may affect outcomes.

The conclusions from several recent SRs that have been conducted on the efficacy of SMT for LBP are summarized in Table 17-3.

TABLE 17-3 Summary Conclusions From Other Systematic Reviews on Spinal Manipulation Therapy for Chronic Low Back Pain

| Reference | Author, Year | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|

| 70 | Ernst, 2006 | Evidence against efficacy of SMT for CLBP |

| 55 | Ferreira, 2002 | Inconclusive evidence about efficacy of SMT for CLBP |

| 74 | van Tulder, 1997 | Evidence supporting efficacy of SMT for CLBP |

| 75 | van Tulder, 2006 | Evidence supporting efficacy of SMT for CLBP |

| 3 | Bronfort, 2004 | Evidence supporting efficacy of SMT for CLBP |

Randomized Controlled Trials

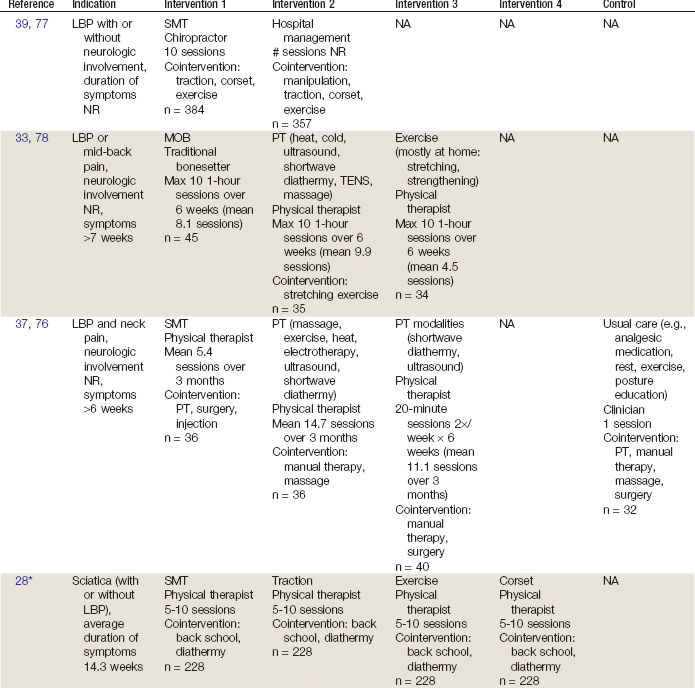

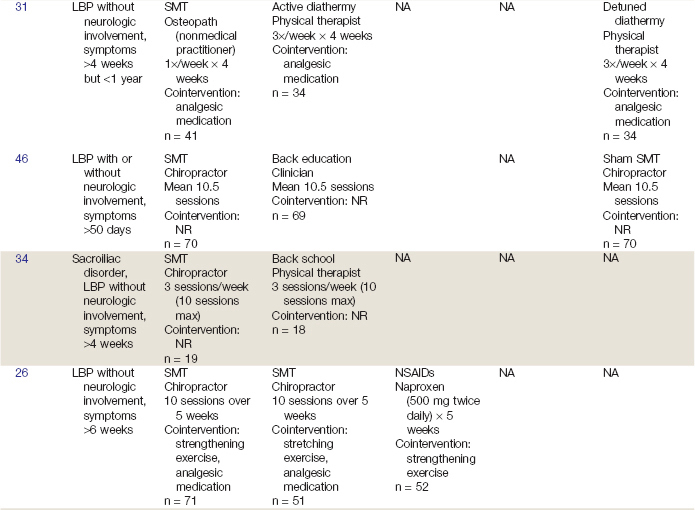

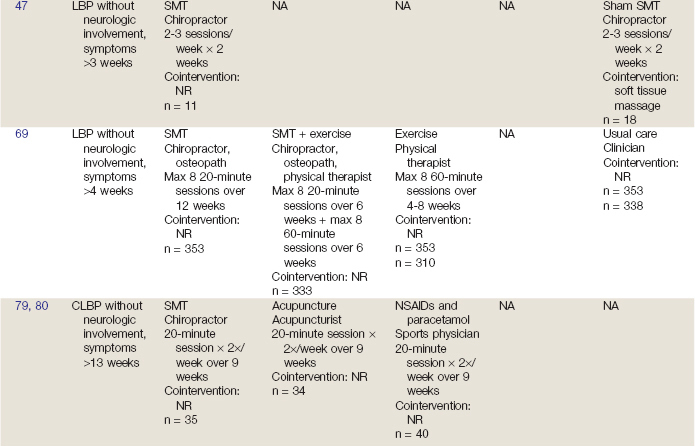

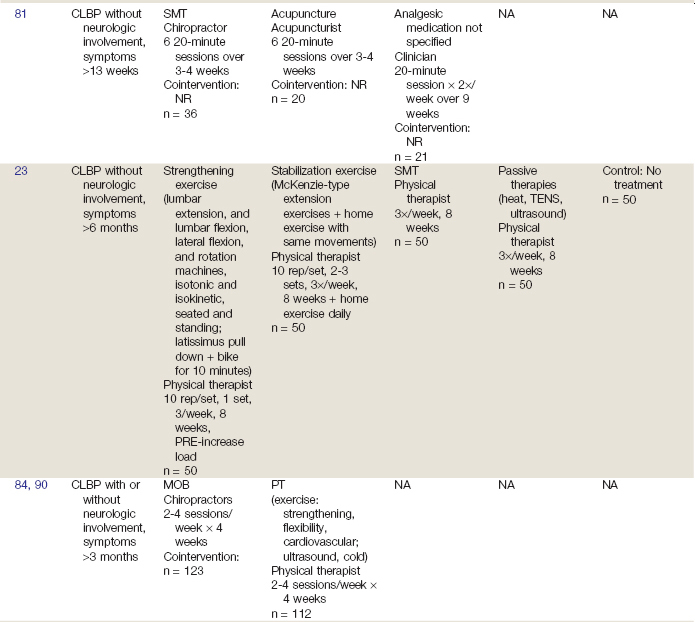

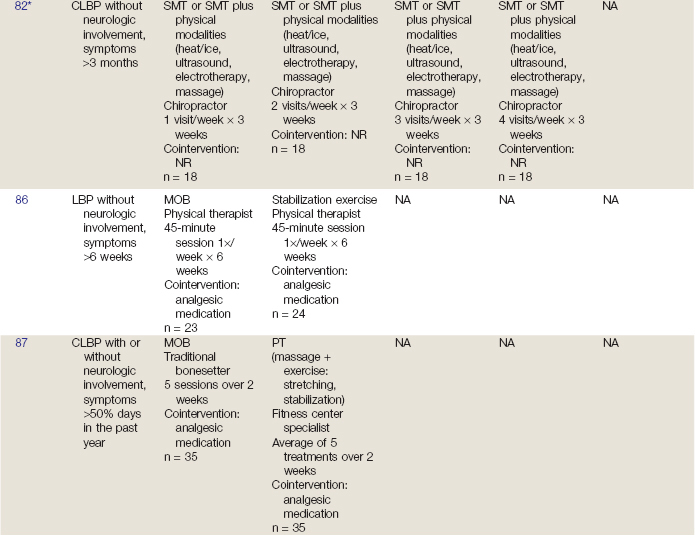

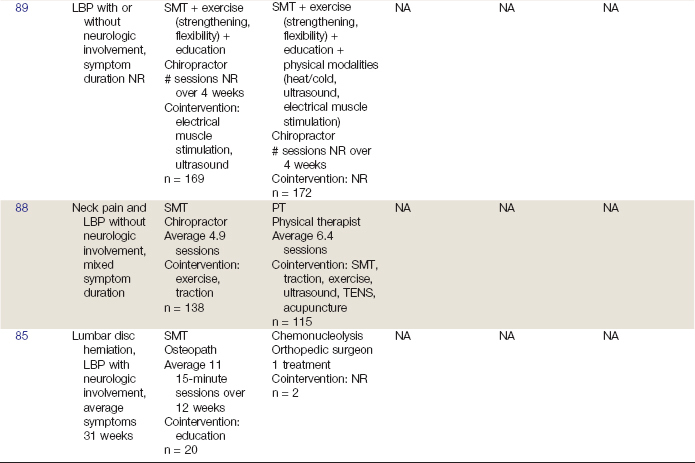

Twenty RCTs and 25 reports related to those studies were identified.23,26,28,31,33-34,37,39,46-47,69,76-89 Their methods are summarized in Table 17-4. Their results are briefly described here.

TABLE 17-4 Randomized Controlled Trials of Spinal Manipulation Therapy or Mobilization for Chronic Low Back Pain

Koes and colleagues37,76 conducted an RCT including patients with LBP or neck pain lasting longer than 6 weeks. It should be noted that our group was able to obtain data from these study investigators in which outcomes were reported separately for LBP and neck pain; our conclusions for between group differences are based on these data rather than those in published reports. Inclusion based on neurologic involvement was not reported. Participants were randomized to one of four groups: (1) SMT, (2) PT (e.g., massage, exercise, heat, ultrasound), (3) PT modalities (e.g., detuned shortwave diathermy, ultrasound), or (4) usual care (e.g., analgesic medication, rest, exercise, posture education). Physical therapists delivered SMT, PT, and PT modalities, while a clinician delivered usual care. Participants in the SMT group received an average of 5.4 sessions over 3 months, while those in the PT and PT modalities groups received an average of 14.7 and 11.1 sessions, respectively, over 3 months. The usual care group received one session only. After 12 months, those in the SMT and PT groups experienced statistically significant improvement in pain and function versus baseline scores.

Meade and colleagues39,77 conducted an RCT including patients with LBP with or without neurologic involvement; duration of symptoms was not reported. Participants were randomized to either SMT performed by a chiropractor or hospital care (including SMT, along with other interventions). The SMT group received a maximum of 10 sessions, while the number of sessions for the hospital care group was not reported. After 3 years, those in the SMT group experienced statistically significant improvement in pain and function versus those in the hospital care group.

Coxhead and colleagues28 conducted an RCT including patients with sciatic pain (with or without LBP). They did not specify a minimum symptom duration but participants had LBP for an average of 14.3 weeks before entering the trial. Participants were randomized to 1 of 4 groups: (1) SMT, (2) traction, (3) exercise, or (4) corset. All groups were also given diathermy and participated in back school. Physical therapists delivered the intervention over 5 to 10 sessions. After 4 weeks, those receiving SMT experienced statistically significant improvement in pain versus those receiving the other interventions.

Gibson and colleagues31 conducted an RCT including patients with LBP without neurologic involvement. In order to be included, participants had to experience LBP for more than 4 weeks but less than 1 year. Participants were randomized to one of three groups: (1) SMT, (2) active diathermy, or (3) detuned diathermy. The SMT group received one session per week over 4 weeks, which was administered by an osteopath who was a nonmedical practitioner. The active and detuned diathermy groups received three sessions per week over 4 weeks, which was administered by a physical therapist. After 4 weeks of follow-up, all groups experienced statistically significant improvement in pain versus baseline scores. Between-group comparisons were not conducted because the authors reported these were not possible.

Hemmilä and colleagues33,78 conducted an RCT including patients with LBP or mid-back pain lasting longer than 7 weeks. Inclusion based on neurologic involvement was not reported. Participants were randomized to one of three groups: (1) MOB performed by a traditional bonesetter, (2) PT (including heat, cold, ultrasound, shortwave diathermy, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation [TENS], massage), or (3) exercise (stretching and strengthening usually performed at home). The MOB group received the intervention from practitioners with no formal medical training, while the PT and exercise groups received the intervention from physical therapists. The mean number of sessions per group over the 6-week intervention was 8.1 for the MOB, 9.9 for the PT, and 4.5 for the exercise groups. After 1 year of follow-up, those in the MOB group experienced statistically significant improvement in disability versus those in the exercise group.

Triano and colleagues46 conducted an RCT including patients with LBP with or without neurologic involvement. In order to be included, participants had to experience LBP for at least 50 days. Participants were randomized to one of three groups: (1) SMT, (2) back education, or (3) sham SMT. All groups received an average of 10.5 sessions. SMT and sham SMT were administered by a chiropractor and a clinician administered back education. After 4 weeks of follow-up, no statistically significant differences were observed between groups.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree