KEY CONTENT

Soft tissue infections characterized by extensive necrosis of subcutaneous tissue, fascia, or muscle are uncommon, but they require prompt recognition and urgent surgical treatment.

The classic hallmarks of necrotizing soft tissue infections are extensive involvement of the subcutaneous tissues and a relative paucity of cutaneous involvement until late in the course of the infection.

Rapidly spreading soft tissue infections present acutely with severe systemic toxicity.

Successful management of these critically ill patients depends on prompt diagnosis by clinical and radiologic means.

The principles of management include fluid resuscitation, hemodynamic stabilization, a broad-spectrum antimicrobial regimen, and early surgical intervention.

Prompt surgery, in which a definitive diagnosis is reached and all necrotic tissue is debrided, should be considered the mainstay of treatment.

The mortality rate is highest when the diagnosis is delayed or initial surgical treatment is limited.

CLASSIFICATION OF SOFT TISSUE INFECTIONS

In severe soft tissue infections, the initial cutaneous presentation often belies the relentless progression of subcutaneous tissue necrosis and dissection that lies beneath a normal-appearing skin. Successful management of these soft tissue infections depends on early recognition, appropriate investigations to establish a specific diagnosis, and combined surgical and medical intervention. A clear understanding of a classification of these entities is required, but, unfortunately, the published literature in this area may be confusing because of a lack of uniformity in descriptive terminology and the use of different classification schemes. The confusion is compounded by the fact that certain clinical entities may involve one or more anatomic planes within the subcutaneous tissue, and one or more bacterial species may be responsible for the same or different clinical entities. Although classification schemes based on microbial etiology may be the most complete, they offer little to the clinical diagnostic process necessary to expedite appropriate management.1 To place a useful clinicoanatomic classification into perspective, a review of the basic anatomy and microbial ecology of the skin and subcutaneous tissues is necessary.

The skin consists of an outer layer, the epidermis, and an inner layer, the dermis, which resides on a fibrous connective tissue layer, the superficial fascia. Beneath this layer, the avascular deep fascia overlies and separates muscle groups and acts as a mechanical barrier against the spread of infections from superficial layers to the muscle compartments. Between the superficial and deep fascia lies the fascial cleft, which is mainly composed of adipose tissue and contains the superficial nerves, arteries, veins, and lymphatics that supply the skin and adipose tissue.

Our understanding of the numbers and types of microbial species present on the skin has significantly changed with the use of 16S ribosomal RNA techniques, directly from their genetic material, compared to previous microbiological culture.2,3 This understanding will likely continue to evolve with additional work being conducted on the Human Microbiome Project, which will undertake to fully characterize the human microbiota.2

Normally, the skin has a resident and a transient flora. The resident flora includes both bacteria and fungi but bacteria are most prevalent. The gram-positive cocci, including corynebacteria, propionibacteria, coagulase-negative staphylococci, Micrococcus, streptococci, lactococci, and Bacillus make up over 75% of the skin flora. Certain areas of the body such as the buttocks, perineum, fossae and web spaces between the digits contain a more diverse flora and some gram-negative bacteria may be found including Acinetobacter, Serratia, Pseudomonas, and occasionally anaerobic gram-negative bacteria.3,4Staphylococcus aureus is not considered part of the resident flora, but colonization rates of 10% to 30% in the anterior nares, axillae, groins, and perineum are not uncommon. The transient flora is made up of bacteria that are collected from extraneous sources and colonize the cutaneous surface for only a short period (hours to days). These organisms are highly variable but often include pathogenic gram-negative bacilli such as Escherichia coli, Proteus species, Klebsiella–Enterobacter species, among others.5 Critically ill patients frequently have compromised natural defense barriers, with concomitant increases in transient flora colonization.6

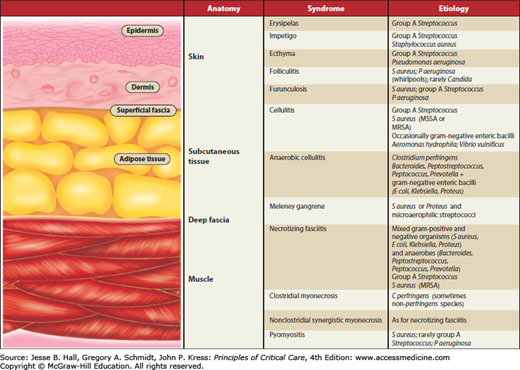

Most classification schemes for soft tissue infections are based on clinical presentation and/or microbiologic etiology.5,7,8Figure 74-1 provides a practical approach to the classification that is based on the affected anatomic plane of the soft tissues, the most commonly encountered clinical terms, and the microbial etiology. With respect to the terminology, it is important to recognize that many authors and professional societies are urging the use of the more simplified terms, nonnecrotizing and necrotizing soft tissue infections, to describe these entities, not only to avoid the confusion over terminology but because they often share a common pathophysiology, diagnostic schemes, and management strategies.1,7 The classification provided illustrates the classical terminology, which is still frequently used clinically and also facilitates the understanding of the primary soft tissue planes involved in these soft tissue infections. Depending on the stage of presentation and the rate of spread, it is important to recognize that an infectious process that initially may have primarily involved a specific anatomic plane may have progressed to multiple soft tissue planes.

The common superficial pyodermas include erysipelas, impetigo, ecthyma, furunculosis, and carbunculosis. These entities do not extend beyond the skin or its appendages and are not discussed further.

The cellulitides include what is commonly referred to as cellulitis, anaerobic (or gangrenous) cellulitis, and the clinically distinctive variant of gangrenous cellulitis called progressive bacterial synergistic gangrene (Meleney gangrene). Cellulitis is an acute spreading infection of the skin extending below the superficial fascia and involving the upper half of the subcutaneous tissues. These infections do not involve the deep fascial layer. The production of gas by anaerobic organisms and the subsequent presence of soft tissue gas, either palpable or demonstrable radiographically, and the propensity to produce necrosis in the subcutaneous tissue (and eventually in the skin) are major differentiating features of anaerobic and classic cellulitis. Both of these latter entities may progress to suppuration and lead to a subcutaneous and/or cutaneous abscess. Progressive bacterial synergistic gangrene (Meleney gangrene) was the original term used to describe a distinct form of cellulitis often occurring postoperatively, with necrotic ulcer formation in the center of a cellulitic area.9

Necrotizing fasciitis is an acute infection involving the deep fascia, subcutaneous tissue, and superficial fascia to variable degrees.10 The muscle tissue beneath the deep fascia is unaffected. The skin may not be involved early in the course of the infection, but as the process continues the skin becomes involved. Fournier syndrome (or gangrene) is a form of necrotizing fasciitis that affects the scrotum and genitalia.11 In this setting, because there is virtually no subcutaneous fat between the epidermis and dartos fascia, cutaneous gangrene readily develops.

The myonecroses include clostridial myonecrosis (otherwise known as gas gangrene), nonclostridial myonecrosis (which has also been termed synergistic necrotizing cellulitis, although that is a misnomer), pyomyositis, and vascular gangrene. Rapid necrosis of the muscle and subsequent necrosis of the overlying subcutaneous tissue and skin are characteristic of the myonecrotic syndromes. Pyomyositis, an exception, is a bacterial abscess localized to the muscle, usually occurring after penetrating trauma. Vascular gangrene occurs in a limb devitalized by arterial insufficiency.

MAJOR SOFT TISSUE INFECTIONS

Pathogenesis: Cellulitis most often occurs secondary to trauma of the skin with local inoculation of microorganisms, secondary to an underlying skin lesion or a postoperative wound infection, or by contiguous spread from a suppurative infection of other soft tissues or bone. However, cellulitis may also occur in the absence of any obvious local trauma. After inoculation of microorganisms into the subcutaneous tissues and skin, an acute inflammatory response is seen in the epidermis, dermis, adipose tissue, and superficial fascia, to varying degrees.

Etiology: The most common organisms causing classic cellulitis are Streptococcus pyogenes and S aureus, with other streptococci (groups B, C, F, and G), Streptococcus pneumoniae, and gram-negative bacilli encountered less frequently. Over the past decade, community-associated methicillin-resistant S aureus (CA-MRSA), predominantly of the USA 300 pulsotype and containing the Panton-Valentine leukocidin, has been increasingly associated with a progressive type of cellulitis, often suppurating and causing large subcutaneous abscesses.12 Cellulitis due to gram-negative bacilli including Escherichia coli, Klebsiella-Enterobacter species, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and yeast such as Cryptococcus neoformans occurs primarily in immunosuppressed or granulocytopenic patients. A severe form of cellulitis may occur in individuals exposed to Aeromonas hydrophila in fresh water, when the organism gains access through lacerations during swimming or wading.13 A severe and fulminant form of cellulitis that progresses rapidly to necrosis and bacteremia may be caused by Vibrio species, especially Vibrio vulnificus, acquired by exposure of a traumatic wound to salt water or raw seafood drippings.7,14

Presentation: Classic cellulitis is characterized by erythema, pain, edema, and local tenderness involving an area of the skin with ill-defined borders. The area of initial cutaneous involvement expands rapidly. There may be associated lymphangitis and regional lymphadenopathy. Systemic manifestations include fever, malaise, and rigors. With untreated or rapidly progressive cellulitis, the process may spread to involve an entire extremity, producing severe systemic toxicity. Dehydration, mental apathy or obtundation, disseminated intravascular coagulopathy, respiratory failure, and septic shock may follow, necessitating intensive care management.

Management: Appropriate laboratory diagnostic studies should be performed before antimicrobial therapy is begun. Any skin abrasions or draining sites should be swabbed for immediate Gram stain and culture. The stain is examined for the presence of organisms, their morphologic appearance, and the number and types of cells. Fine needle aspiration into the leading edge of the cellulitis may be attempted; potential pathogens have been isolated in 10% to 38% of cases.15,16 A combination of needle aspiration, skin biopsy, and blood cultures results in isolation of pathogens in approximately 25% of cases.17

For severe infections in which streptococci and methicillin-susceptible staphylococci are considered possible, parenteral administration of a large-dose penicillinase-resistant penicillin (nafcillin or cloxacillin), 8 to 12 g/day in four or six divided doses, is most appropriate. Alternate agents include a first-generation cephalosporin, such as cefazolin (6 g/day in three divided doses), vancomycin (2 g/day in two divided doses), or clindamycin (1200-2400 mg/day in three divided doses). In settings where community- or hospital-associated MRSA predominate, which is increasingly encountered in many jurisdictions, vancomycin (2 g/day in two divided doses) or another agent with reliable activity against MRSA in skin and soft tissue infections, including linezolid, daptomycin, or ceftaroline is indicated.7,18 An additional approach recommended by some authors is to use a penicillinase-resistant penicillin (nafcillin or cloxacillin) or a first-generation cephalosporin in addition to vancomycin.19 If the etiologic agent proves to be streptococcal, penicillin G should be substituted (6-12 million U/day). In the immunocompromised host, empiric broad-spectrum administration of agents active against both gram-positive, including MRSA, and gram-negative organisms is appropriate such as a combination of vancomycin plus an antipseudomonal cephalosporin or a carbapenem or an aminoglycoside plus an extended spectrum penicillin agent.18 In the presence of a rapidly progressive cellulitis developing after a freshwater or saltwater exposure, where Aeromonas or Vibrio, respectively, may be potential pathogens, alternative agents are more appropriate . Aminoglycosides, third-generation cephalosporins, and carbapenems have reliable activity versus Aeromonas hydrophila and any of these agents represents an appropriate empiric choice. A combination of a third-generation cephalosporin (cefotaxime or ceftazidime) with doxycycline has synergistic activity against Vibrio vulnificus and some reports have suggested an improved outcome with this combination for the treatment of Vibrio vulnificus infections.20

Local care of cellulitis includes immobilization and elevation of the affected area. These measures are most appropriate when an extremity is affected. Analgesic drugs are administered as necessary. Cool compresses may help alleviate pain. The extent of the cellulitis should be outlined on the skin with an appropriate marker at the time of admission to facilitate objective daily assessments of the extent of spread. Frequent inspection of the involved area is necessary to detect the development of any areas of crepitus or suppuration, which may require surgical drainage. Abscesses of the subcutaneous tissue are not infrequent after extensive cellulitis; judicious use of repeated needle aspiration may be necessary. Failure to achieve defervescence and a decrease in systemic toxicity within 48 to 72 hours after institution of appropriate antimicrobial therapy should arouse suspicion of suppuration or a more virulent soft tissue infection, such as necrotizing fasciitis or myonecrosis.

Pathogenesis: The term anaerobic cellulitis is not properly descriptive, and many terms are used for this process including gas abscess, gangrenous cellulitis, localized gas gangrene, necrotizing cellulitis, and epifascial gangrene. The process usually represents infection of already devitalized subcutaneous tissue without involvement of the deep fascia or underlying muscle. Microorganisms are introduced into the subcutaneous tissues from an operative or traumatic wound or from a preexisting local infection. The subcutaneous tissues are devitalized owing to a local injury, an inadequately debrided wound, or a metabolic disturbance that compromises vascular supply (eg, diabetes mellitus). Usually, the infectious process is not invasive but instead remains localized in the area of devitalized tissue.21,22 Extensive gas formation and suppuration, usually limited to the area of devitalized tissue, are present.

Etiology: Anaerobic cellulitis may be clostridial or nonclostridial. Clostridium perfringens is the most commonly isolated clostridial species, followed by Clostridium septicum. Gram-negative rods, staphylococci, or streptococci are occasionally present but are not the predominant isolates. The nonclostridial form of anaerobic cellulitis is essentially the same process as clostridial cellulitis, but has a different microbiologic etiology. Obligate anaerobes are the predominant isolates, with Bacteroides fragilis, other Bacteroides species, Prevotella species, Porphyromonas species, Peptostreptococcus and Peptococcus species encountered most frequently. Other bacteria that may be present include the gram-negative enteric bacilli (Escherichia coli and Klebsiella species), staphylococci, and streptococci.

Presentation: The clinical pictures of clostridial and nonclostridial anaerobic cellulitis are very similar and may be discussed together. Because this infection represents the local invasion of already devitalized tissue, the process does not generally have a virulent progressive course. The onset is gradual, with mild to moderate local pain and only mild to moderate tissue swelling. Constitutional symptoms are not prominent; the relative paucity of symptoms is helpful in distinguishing this entity from myonecrotic infections. A thin, dark, malodorous discharge from the wound or inoculation site, sometimes containing fat globules, with extensive and prominent gas formation, is characteristic. A dusky erythema may be present, and there may be extensive crepitus in the involved area. Although not initially invasive beyond the area of devitalized tissue, the condition must not be considered benign. If it is inadequately managed, the infection will eventually spread and lead to a rapid and extensive undermining of the skin similar to that seen in necrotizing fasciitis, with corresponding systemic toxicity.

A distinctive variant of gangrenous cellulitis was described and named by Meleney several decades ago.9 It has been called progressive bacterial synergistic gangrene, postoperative progressive gangrene, Meleney gangrene, and—if associated with burrowing necrotic tracts producing distant lesions—Meleney ulcer. The process usually begins postoperatively, particularly after abdominal or thoracic procedures, with a slowly developing shaggy ulcer with a gangrenous center surrounded by an inner zone of purple discoloration, which in turn is surrounded by an outer zone of erythema. Without treatment, the course is one of relentless indolent extension, but without significant systemic toxicity. Satellite lesions may occur, which represent tracts of burrowing subcutaneous infection that surface to produce a gangrenous ulcer on the skin. Pathologically, the process is usually limited to the upper third of the subcutaneous fat, but occasionally it extends down to fascia. The lesion was originally thought to be caused by a synergistic interaction between microaerophilic streptococci and S aureus, but other microorganisms, including Proteus species and other gram-negative enteric bacilli, have been implicated.