Key Clinical Questions

Does this patient have malabsorption?

Is the malabsorption due to celiac disease?

What other diseases need to be considered?

What are the consequences of malabsorption?

How is malabsorption managed?

What are common causes of small bowel obstruction?

How do patients present with small bowel obstruction?

When do patients with small bowel obstruction need to go to surgery and when can they be managed medically?

Can small bowel obstruction be prevented?

What conditions predispose to small bowel ileus?

Can small bowel ileus be prevented?

How is small bowel ileus treated?

When can a patient resume oral intake?

Malabsorption and Celiac Disease

Numerous causes lead to malabsorption and maldigestion, ranging from the common to the obscure. Lactose intolerance, for example, is present in 7% to 20% of Caucasian adults, 50% of Hispanics, 65% to 75% of African Americans, and 90% in some East Asian populations. Celiac disease is most commonly seen in whites of northern European ancestry. In a large screening study from the United States, the prevalence of celiac disease in average risk individuals was 1:133. The prevalence was highest in first-degree relatives of a patient with celiac disease (1:22). Other disorders, such as primary intestinal lymphangiectasias, occur so rarely that it is difficult to estimate their true prevalence.

Patients with malabsorption often report weight loss, diarrhea, anorexia, flatulence, borborygmi, and/or greasy, foul smelling, voluminous pale stools. Patients may also have symptoms related to specific micronutrient deficiencies (Table 161-1). Some patients, however, are asymptomatic.

| Nutrient | Symptoms of Malabsorption | Laboratory Abnormalities |

|---|---|---|

| Fat |

|

|

| Carbohydrates |

|

|

| Protein |

|

|

| Vitamin B12 |

|

|

| Folate |

|

|

| Iron |

|

|

| Calcium and vitamin D |

|

|

| Vitamin A |

|

|

| B vitamins |

|

|

| Vitamin K |

|

|

Malabsorption refers to impaired nutrient absorption, whereas maldigestion refers to impaired digestion of nutrients within the gut lumen or at the brush border. The term malabsorption, however, is often used to encompass both processes since digestion is a required step for absorption. Three steps comprise nutrient absorption. The first is luminal processing, in which ingested nutrients are broken down into absorbable subunits. The second is absorption of nutrients into the intestinal mucosa. The third is the transport of the nutrients into the circulation. Malabsorption can occur if any of these steps are disrupted.

Malabsorption can be either global or partial. Global malabsorption occurs when there is diffuse mucosal involvement or reduced absorptive surface, seen in disorders such as short gut syndrome or celiac disease. Partial malabsorption refers to the malabsorption of specific nutrients, such as vitamin B12 malabsorption in pernicious anemia or Crohn disease with involvement of the terminal ileum (the site of vitamin B12 absorption).

Fat digestion and absorption depend upon fat hydrolysis, primarily by pancreatic enzymes (lipase, colipase). The fatty acids then combine with bile salts, lipids, and fat soluble vitamins to form micelles and liposomes, which subsequently cross the microvillus membrane. Once within the enterocytes, the fatty acids are transported to the endoplasmic reticulum where chylomicrons form and are transported into the lymphatics. Diseases such as chronic pancreatitis interfere with fat digestion and absorption, resulting in fat malabsorption (Table 161-2).

| Disorder | Affected Nutrient(s) | Mechanism(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Chronic pancreatitis | Fat | Lipase and colipase deficiencies |

| Carbohydrate | Pancreatic amylase deficiency | |

| Protein | Protease deficiencies | |

| Cystic fibrosis | Protein | Impaired protease excretion |

| Zollinger-Ellison syndrome | Fat, protein | Digestive enzyme inactivation |

| Cirrhosis | Fat, fat soluble vitamins | Decreased bile salt production |

| Chronic cholestasis | Fat, fat soluble vitamins | Impaired bile salt secretion |

| Bacterial overgrowth | Fat, fat soluble vitamins | Bile salt deconjugation |

| Carbohydrate | Damage to brush border enzymes | |

| Protein, carbohydrate, vitamin B12 | Consumption of nutrients by bacteria | |

| Lactose intolerance | Lactose | Lactase deficiency |

| Celiac disease, tropical sprue, common variable immunodeficiency | Carbohydrate | Decreased brush border enzyme activity due to villous damage |

| Carbohydrate, protein, fat | Decreased absorptive surface area | |

| Short bowel syndrome | Fat, carbohydrate, protein, vitamin B12 | Decreased absorptive surface area |

| Pernicious anemia | Vitamin B12 | Impaired production of intrinsic factor |

| Ileal disease (eg, Crohn, lymphoma, amyloid) | Vitamin B12 | Decreased absorptive surface |

| Intestinal lymphangiectasia | Fat, fat soluble vitamins | Impaired transport into lymphatics |

Carbohydrate digestion involves the breakdown of complex carbohydrates (starches) and disaccharides into monosaccharides, which are then absorbed by active and passive transport into enterocytes. Starch digestion requires amylase (salivary and pancreatic) to break the complex sugars into oligo- and disaccharides, which are then broken down into monosaccharides by brush border enzymes (primarily disaccharidases). Ingested disaccharides, such as lactose and sucrose, are also broken down by brush border disaccharidases. Disorders leading to carbohydrate malabsorption (Table 161-2) result in the maldigested and malabsorbed carbohydrates passing into the colon, where they are degraded by bacteria through fermentation, resulting in the production of short chain fatty acids, hydrogen, carbon dioxide, and methane.

The goal of protein digestion is to break proteins down into components that are capable of being absorbed. As with fat and carbohydrate digestion, disorders that impair protein digestion or absorption result in protein malabsorption (Table 161-2). Protein digestion starts with gastric pepsins. Then proteases secreted by the pancreas into the duodenum act on the partially digested proteins, resulting in the production of amino acids, dipeptides, and tripeptides. Selective transporters move neutral, basic, and acidic amino acids, as well as dipeptides and tripeptides, from the gut into the bloodstream.

Vitamins, minerals, and trace elements have many different transport mechanisms including passive diffusion, carrier-mediated passive transport, and active transport. Most are absorbed in the proximal half of the small intestine. Two notable exceptions are vitamin B12 and magnesium, which are absorbed distally. Some examples of disorders associated with vitamin, mineral, and trace element deficiencies are shown in Table 161-2.

Celiac disease occurs as a result of immune mediated damage to the small bowel mucosa. Certain gliadin peptides can initiate an innate immune response in macrophages, monocytes, dendridic cells, and intestinal epithelial cells. Intraepithelial lymphocytes and autoantibodies to tissue transglutaminase may also play a role in the pathogenesis of celiac disease. The end result is damage to the small intestinal villi, which results in malabsorption due to decreased surface area and damage to brush border enzymes.

Numerous conditions cause malabsorption, including celiac disease, small bowel bacterial overgrowth, Crohn disease with small bowel involvement, chronic pancreatitis, short bowel syndrome, protein losing enteropathy, intestinal lymphangiectasias, amyloid, small bowel lymphoma, eosinophilic gastroenteritis, common variable immunodeficiency, lactose intolerance and other disaccharidase deficiencies, and Zollinger-Ellison syndrome (Table 161-2).

Disorders that may mimic malabsorption include irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea and/or bloating, microscopic colitis, and laxative abuse. In the case of irritable bowel syndrome and microscopic colitis, patients should not have nutrient deficiencies or lose weight.

Taking a careful history is the first step in diagnosing malabsorption. In addition to eliciting symptoms that are suggestive of malabsorption, the history can also help identify possible causes of malabsorption (eg, short bowel syndrome in a patient who has undergone a partial small bowel resection), as well as guide further testing. Conditions associated with celiac disease include dermatitis herpetiformis, diabetes mellitus, selective IgA deficiency, Down syndrome, liver disease, and thyroid disease.

The physical exam can give clues about underlying conditions that predispose to malabsorption, such as an abdominal scar in the case of a patient who has had a small bowel resection. The exam may also show evidence of nutritional deficiencies, such as pallor in the setting of anemia and neurologic abnormalities in the setting of vitamin B12 deficiency (Table 161-1).

Various routine laboratory tests may suggest malabsorption (Table 161-3). To test for fat malabsorption, the initial test often obtained is a Sudan stain of the stool. This test will identify more than 90% of patients with clinically significant steatorrhea. However, its overall sensitivity and reliability are limited by variability in the performance and interpretation of the test. If fat malabsorption is suspected, a 72-hour fecal fat determination serves as the gold standard. Normal individuals will absorb 94% of the fat that is ingested. The stool should be collected and refrigerated for 72 hours with the patient on a 100 gm of fat per day diet. Excretion of more than 6 gm of fat is abnormal, though values up to 14 gm per day have been seen in volunteers in whom diarrhea was induced and in patients with a stool weight of greater than 1000 gm per day (normal is < 200 gm per day). Patients with true steatorrhea typically have fecal fat excretion of more than 20 gm of fat per day. While testing for protein malabsorption is not generally performed, enteral protein loss can be demonstrated by measuring alpha-1 antitrypsin clearance. In this test, stool is collected for 24 hours, along with a serum measurement of alpha-1 antitrypsin. Clearance is calculated by dividing the product of the fecal alpha-1 antitrypsin and the stool volume by the serum concentration of alpha-1 antitrypsin. In protein losing enteropathy, the value is typically greater than 100 mg/mL.

| Decreased | Increased |

|---|---|

| Hemoglobin, iron, ferritin, total iron binding capacity | Urine oxalate |

| Folate (serum or red blood cell) | Prothrombin time |

| Vitamin B12 | Stool fat |

| Calcium | |

| Magnesium | |

| Cholesterol | |

| Carotene | |

| Albumin |

Laboratory testing can be particularly useful in the evaluation of celiac disease. In addition to nonspecific findings, such as iron deficiency, specific tests for celiac disease include antibodies to tissue transglutaminase (anti-TTG), which are highly sensitive and specific (95% and 94%, respectively). Tests can detect both IgA and IgG individually, which is important, since celiac is associated with selective IgA deficiency.

If celiac disease is suspected, serologic testing should be obtained for antitissue transglutaminase and antiendomysial antibodies (with testing to confirm normal IgA levels). If IgA levels are low, IgG-based testing for antitissue transglutaminase or antigliadin antibodies should be obtained. An IgA endomysial assay is highly specific, but only moderately sensitive for detecting celiac disease in untreated patients, and will frequently be falsely negative in patients with celiac disease who are on a gluten free diet. Antigliadin antibody testing has only moderate sensitivity and specificity and the positive predictive value in a general population is poor.

|

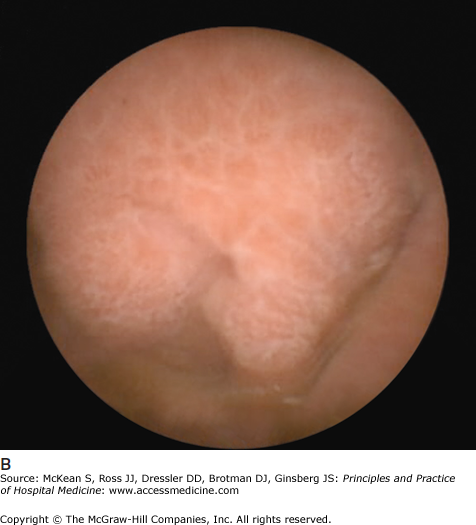

Some causes of malabsorption will be apparent on upper endoscopy. In the case of celiac disease, the duodenal mucosa may appear scalloped with a mosaic pattern and decreased duodenal folds (Figure 161-1). In Crohn disease the mucosa may have a cobblestone appearance. (See Chapter 163 Inflammatory Bowel Disease.) Biopsies should always be obtained, as the findings may be subtle and not discernable to the endoscopist. Biopsies in celiac disease will demonstrate villous blunting with crypt elongation and an increase in intraepithelial lymphocytes. However, not all villous blunting is due to celiac disease. Other conditions that may result in villous blunting include bacterial overgrowth, common variable immunodeficiency, autoimmune enteropathy, Crohn disease, eosinophilic gastroenteritis, giardiasis, lymphoma, peptic duodenitis, gastroenteritis, tropical sprue, Zollinger-Ellison syndrome, and other immunodeficiency states.

Colonoscopy with intubation and biopsy of the terminal ileum may aid in making a diagnosis of Crohn disease. Additionally, random biopsies obtained from the colon may help to exclude alternative diagnoses, such as microscopic colitis.

An advantage of wireless capsule endoscopy over standard endoscopy is that it allows for visualization of the entire small bowel. While generally not required to make a diagnosis of celiac disease (which typically involves the proximal small bowel), the procedure can be helpful in diagnosing other small bowel disorders with mucosal involvement, such as Crohn disease and lymphoma. It is also useful in patients with known celiac disease who are not responding to a gluten free diet. In these patients, considerations include inadvertent gluten ingestion, enteropathy associated T-cell lymphoma, ulcerative jejunitis and refractory celiac disease (ie, celiac disease that does not respond to strict gluten restriction). A disadvantage of wireless capsule endoscopy is that it does not allow for biopsies to be obtained. Additionally, it is contraindicated in patients with suspected small bowel obstructions.

ERCP and EUS are sometimes employed to help make a diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis. Findings on ERCP include a dilated, irregular pancreatic duct and stones within the pancreatic duct. However, a normal ERCP does not exclude the diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis. Findings on EUS include both parenchymal and ductal abnormalities. The parenchymal abnormalities of chronic pancreatitis seen on EUS include hyperechoic (white) foci and strands, lobularity, atrophy, cysts, and calcifications. The ductal changes include ductal dilation, irregularity, visible side branches, hyperechoic walls, and pancreatic duct stones. However, the most sensitive finding for chronic pancreatitis is pancreatic function testing, with a reported sensitivity of 80% to 90%. At the time of endoscopy, samples of pancreatic juice are obtained from the duodenum following secretin stimulation. In the setting of chronic pancreatitis, the bicarbonate concentration will be low.

Radiologic testing has only limited value in the evaluation of malabsorption. Small bowel barium studies may show small bowel diverticula that can be associated with small bowel bacterial overgrowth, or mucosal disease that is not easily reached endoscopically (though capsule endoscopy is superior to small-bowel follow-through for detecting mucosal disease). Computed tomography and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) may aid in the diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis.

Bacterial fermentation of undigested carbohydrates is the basis for breath testing. The fermentation results in increases in breath hydrogen, or in the elaboration of radio-labeled carbon dioxide. The tests commonly help diagnose bacterial overgrowth (in which case bacteria digest the carbohydrates within the small bowel) and lactose intolerance. Tests also exist for fructose, sucrose, and isomaltose malabsorption.

While generally managed as outpatients, patients with severe malnutrition or dehydration may need admission for nutritional support, volume repletion, and to correct electrolyte abnormalities.

Treatment of malabsorption aims at correcting nutritional deficiencies and, when possible, correcting the underlying disorder resulting in malabsorption (eg, antibiotic treatment for bacterial overgrowth). Consultation with a dietician is frequently helpful in managing patients with malabsorption. In complicated cases, however, a physician who specializes in nutrition support should be consulted. Significant weight loss (> 10 percent) is associated with increased morbidity and mortality and should be treated aggressively. In some cases, patients may need total parenteral nutrition. Vitamin and mineral deficiencies should be corrected if present. Typically, oral supplementation is sufficient. Patients with significant steatorrhea may need supplementation with fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, and K).

Some patients benefit from nutritional restriction, such as patients with celiac disease who need to avoid all gluten-containing foods. Patients should receive counseling from a nutritionist to help them understand what is involved with being gluten free. Some patients believe they are following a gluten free diet because they are avoiding bread products, not realizing that gluten is present in numerous other foods and products (eg, soy sauce, soups, lunch meats, some toothpastes) (Table 161-4

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree