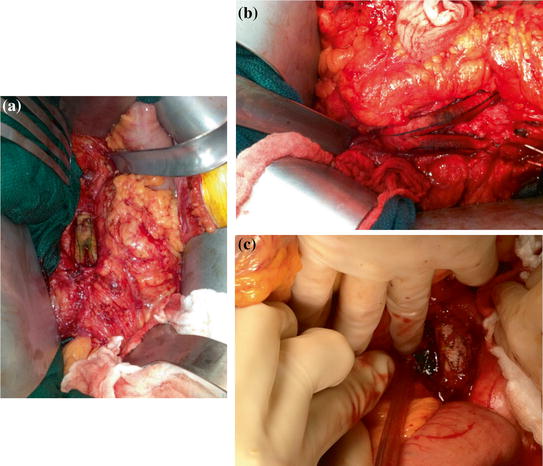

Fig. 12.1

a Anterior displacement of the duodenum by tortuous aortic graft placement resulting in aorto-duodenal fistula (b)

The fistulas are usually all characterized structurally as being stuck to the aorta or graft with a full thickness violation of the bowel wall, the vessel, or graft essentially “patching” the defect. This pathologic structure is at the heart of the presentation of aortoenteric fistulas (Fig. 12.2).

Fig. 12.2

a Exposed, stained aortic graft from an aorto-duodenal fistula (b) from a double fistula to both distal limbs of an aorto-bifemoral graft, the fistula from a segment of small bowel. c Fistula to exposed endostent

Presentation

Aortoenteric fistulae essentially demonstrate two distinctive patterns of presentation. The first is defined by sudden onset of an episode of massive gastrointestinal bleeding. This is painless, often with bright red blood per rectum and initially self-limited. In the setting of primary aneurysmal fistula, it can occur because of connection at any point along the aneurysmal sac. In the setting of prior graft replacement, the fistula usually has formed at one of the suture lines between the graft and the native aorta; at times, the infection of the graft can spread along its course, “un-incorporating” the Dacron material but bleeding still will occur from suture line failure (we have not seen dissolution of the graft material itself). As with other bleeds associated with infectious etiology, the first bleed is often known as a “heralding bleed,” stopping from a combination of hypotension (reducing the pressure at the suture line) allowing acute coagulation. Aggressive resuscitation in the setting of diagnostic uncertainty combined with clot lysis (likely accelerated by active infection and exposure to the digestive ferocity of succus) leads to subsequent episodes of massive hemorrhage (less self-limited). Healthy suspicion, combined with rapid diagnosis, is vital if patients with this presentation are to be successfully treated.

Resuscitation of the patient who presents with gastrointestinal bleeding from an aortoenteric fistula is challenging. At times, massive ongoing bleeding results in severe hemodynamic instability and the patient requires full replenishment of intravascular volume to stabilize. Once the diagnosis is made and intervention is underway, a strategy of judicious hypotensive resuscitation can be employed. This decreases fluid administration and avoids the subsequent disastrous edema that results from excessive fluid administration. Additionally, passive hypotension theoretically reduces the pressure-based risk of disrupting a clot and decreases the rapidity and volume of ongoing hemorrhage. We utilize a strategy of balanced hemostatic resuscitation in our approach with low ratios of transfusion of units packed red blood cell to fresh frozen plasma and platelets. For these patients, we frequently enact our standard institutional massive transfusion protocol.

The second pattern of presentation is more insidious, and likely more common [2, 3]. Slow erosion of the bowel wall results in the continual bathing of a patch of graft with succus or stool. This continual exposure results in episodic bacteremia with poly-microbial exposure and no possibility for sterilization with antibiotic administration, unlike an uncomplicated mono-microbial graft infection (if there really is such a thing). There is often suspicion of a graft infection but not necessarily a proven etiology (imaging findings can be subtle). It is not uncommon for these patients to undergo months of several courses of escalating antibiotic therapy suffering chronic malaise and malnutrition.

Diagnosis

When the presentation is acute, expeditious diagnosis is vital. Confirmation of fistula then allows management planning (this can be a terminal event as not all patients are appropriate operative candidates). CT scanning and endoscopy are the primary modalities to confirm aortoenteric fistula [4, 5]. CT is least invasive and may be immediately diagnostic. Inflammation is generally seen at the fistula site with air, extraluminal to the GI track, as seen along the wall of the aorta or aortic graft [6] (Figs. 12.3 and 12.4). EGD or colonoscopy will often demonstrate the fistula, almost shockingly, by visualizing obvious graft material comprising a large portion of the bowel wall. This too is immediately diagnostic (Fig. 12.5).

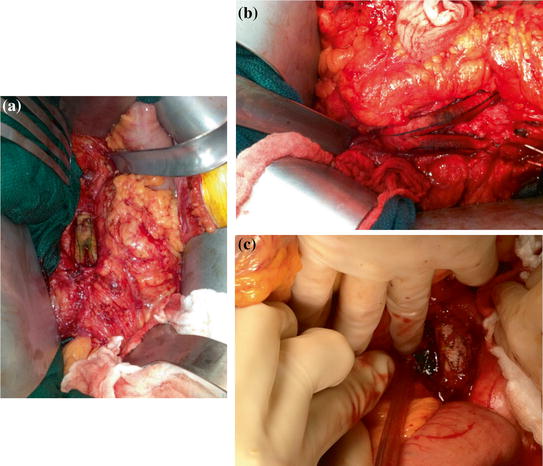

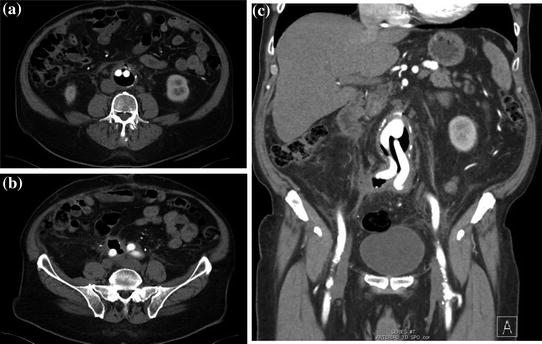

Fig. 12.3

CT of graft with massive amount of air around prosthetic graft (a); b coronal reconstruction; c fistulous connection with overlying sigmoid colon

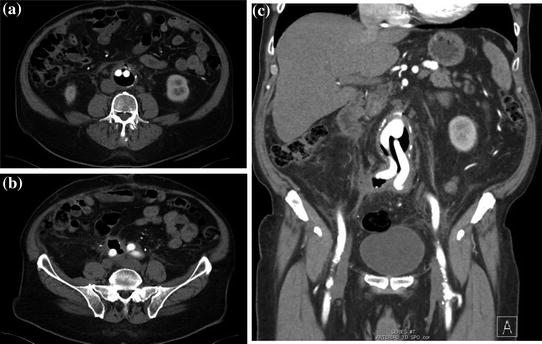

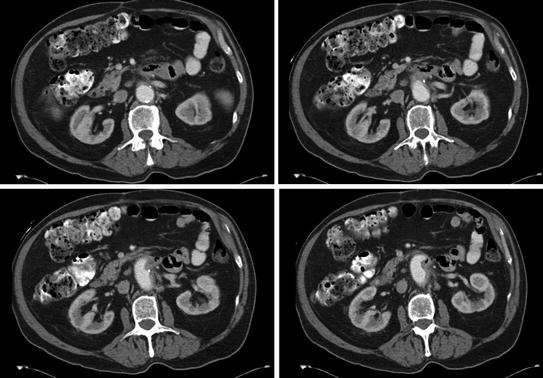

Fig. 12.4

CT of aortic graft with subtle amount of periduodenal inflammation and a spicule of air in the graft bed (right lower frame)

Fig. 12.5

EGD view of posterior wall of fourth portion of the duodenum with visualized prosthetic from the aortic graft

While the CT may suggest some inflammation along the course of the aorta, it is sometimes quite difficult to confirm a fistula (Fig. 12.6). The duodenum is almost always collapsed in its third and fourth portions. Radiographically this can hide wall thickening along the posterior aspect of the duodenum. Further, there is seldom an associated pocket of purulence as the connection to the bowel effectively drains internally and in thin patients, the paucity of fat frequently precludes identification of significant inflammation.

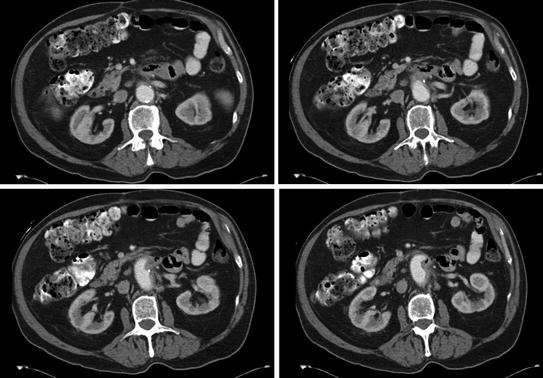

Fig. 12.6

Subtle periduodenal inflammation in a patient with an endostent; confirmed aortoenteric fistula

There is usually no pain associated with aortoenteric fistula formation (sometimes achy back discomfort) and few digestive symptoms. Chronic unwellness is nonspecific but continued elevation of inflammatory indicators, episodic illness, polymicrobial, and shifting bacteremias (especially enteric flora) should heighten suspicion and guide more aggressive diagnostic efforts.

Management

No aortoenteric fistula will heal spontaneously. Operative management is the only solution for correction of aortoenteric fistula. A decision to manage conservatively with ongoing antibiotic regimens is reasonable if the patient is unfit for operative repair, does not want to risk repair, or carries a prognosis from other comorbidities that govern life span (such as metastatic cancer). This is purely a palliative option; the natural history can be expected to be a septic or hemorrhagic death if due to the fistula.

The goals of operative therapy are to (1) assure arterial flow and adequate distal perfusion, (2) detach the connection between the GI track and the arterial system, (3) re-establish GI track integrity, (4) minimize risk of recurrence, and (5) definitively manage the systemic infection. These operations are long, technically challenging and high risk. We have chosen a multidisciplinary approach combining the efforts of both acute care and vascular surgeons with critical care anesthesia and where possible, perfusionists.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree