INTRODUCTION

ULCERS

The vast majority of leg ulcers are venous stasis ulcers resulting from chronic venous insufficiency.1 Chronic venous insufficiency is usually caused by episodes of phlebitis or varicose veins, both of which damage venous valves. This results in poor venous return from the lower extremities, leading to increased hydrostatic pressure and lower extremity edema and stasis dermatitis.

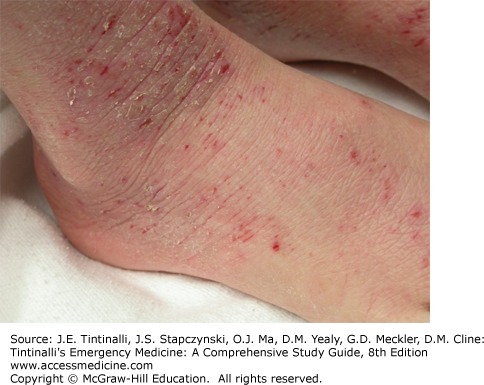

Dependent edema, erythema, and orange-brown hyperpigmentation characterize early stasis dermatitis. The medial distal legs and the pretibial leg are the areas most frequently affected. More chronic and severe cases may have bright weepy erythema and even ulceration (Figure 253-1). Pruritus is common. Cellulitis and lymphangitis may complicate stasis dermatitis. The presence of honey-colored crust and pustules suggests secondary bacterial infection.

Stasis ulcers often begin within areas of stasis dermatitis. The bilateral malleoli and the medial aspect of the calf are the most common sites of involvement. Diagnosis is clinical. With acute exacerbation, secondary infection is common. Table 253-1 lists the differential diagnosis of leg ulcers. Certain disorders, such as arterial ulcerations, pyoderma gangrenosum, and polyarteritis nodosa require immediate attention. If peripheral pulses are diminished or absent, obtain vascular blood flow studies to exclude arterial ulcers. If the patient reports a rapidly developing ulcer that began as a pustule or erythematous nodule and has violaceous overhanging borders, suspect pyoderma gangrenosum. If the diagnosis is in question, consult with a dermatologist.

Trauma Injuries, burns, injections, decubitus, chilblains (pernio), neuropathic ulcers Infections Viral: herpes simplex virus, cytomegalovirus Bacterial: gangrene, ecthyma gangrenosum, ecthyma secondary to Staphylococcusaureus and/or group A Streptococcus; osteomyelitis, methicillin-resistant S. aureus Mycobacterial: Buruli ulcer (West Africa, Mycobacterium ulcerans), Bairnsdale ulcer (Australia, M. ulcerans), tuberculosis, leprosy Fungal: blastomycosis, coccidioidomycosis, paracoccidioidomycosis, chromomycosis, mucormycosis Spirochetal: syphilis, yaws Parasitic: leishmaniasis, amebiasis, schistosomiasis Bites Spiders, scorpions, snakes Metabolic Diabetes, gout, calciphylaxis (cutaneous necrosis from small- and medium-sized vessel calcification in diabetes, end-stage renal disease, or hyperparathyroidism) Vascular Venous: varicose veins, venous insufficiency Arterial: hypertension, arterial insufficiency, thrombosis, embolism Vasculitis Polyarteritis nodosa, vasculitis, collagen vascular disease, Behçet’s syndrome Malignancy Cutaneous: squamous cell carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma Lymphoma: T-cell or B-cell lymphoma Hematologic Polycythemia, sickle cell anemia Dermatologic Bullous pemphigoid, necrobiosis lipoidica Drugs Hydroxyurea |

Treatment of venous stasis dermatitis and ulcers begins with leg elevation and the use of support stockings. Weeping eruptions should be treated with an astringent compress. A low- to mid-potency topical steroid, such as fluocinolone acetonide 0.025% or hydrocortisone 2.5% ointment, should be applied twice a day until erythema, scale, and pruritus resolve. Oral antihistamines, such as diphenhydramine or hydroxyzine, should be used for pruritus and for nighttime sedation. Secondary bacterial infection should be treated with cephalexin, dicloxacillin, or ciprofloxacin for 7 to 10 days. Topical neomycin, antihistamine creams, and anesthetic creams should be avoided because they may complicate the condition with allergic contact dermatitis. Cellulitis or lymphangitis may require hospitalization for IV antibiotics. Otherwise, follow-up should be arranged with a chronic wound care team.1

Pyoderma gangrenosum is a recurrent cutaneous, necrotizing, and noninfective ulceration of the skin that most commonly occurs in women between 30 and 50 years of age.2 Most cases are associated with underlying disease, such as inflammatory bowel disease, rheumatoid arthritis, and myeloproliferative disorders.3

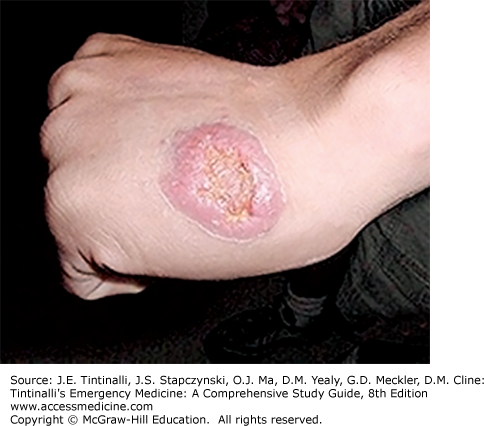

The classic lesion of pyoderma gangrenosum begins as a superficial pustule or erythematous nodule that expands into a large painful ulcer on the lower extremity with a purulent base and irregular, undermined borders and gun metal gray hue (Figure 253-2). There is no associated lymphadenopathy. Up to 50% of patients develop lesions at the sites of trauma, such as surgery sites or injection sites, or after blood drawing.2 A history of multiple surgical debridements with sterile cultures should suggest a potential diagnosis of pyoderma gangrenosum.

The diagnosis is clinical and one of exclusion. Search for associated conditions, such as inflammatory bowel disease and myeloproliferative disorders. The onset of new skin lesions or ulcers at previous sites of trauma can also be helpful in identifying pyoderma gangrenosum.4

Treatment of the underlying disorder and corticosteroids, either topical, intralesional, or combined local and systemic, are the standard therapy for pyoderma gangrenosum. Resistant disease may require adjunctive systemic therapy with immunosuppressive or cytotoxic agents.4

Most patients with diabetic foot ulcers have coexistent diabetic neuropathy.5 Other causes of neuropathic leg ulcers are much rarer and include leprosy, tabes dorsalis, medications, and spinal cord lesions. In most patients with foot ulcers, one will note a triad of neuropathy, deformity, and trauma. Neuropathy leads to atrophy of the intrinsic muscles of the foot, collapse of the arch, and loss of stability of the metatarsal-phalangeal joints. The musculoskeletal alterations result in abnormal pressure points and greater friction on the foot during ambulation. Lack of sensation allows for repeat injury. The most common source of trauma is inappropriate footwear.6

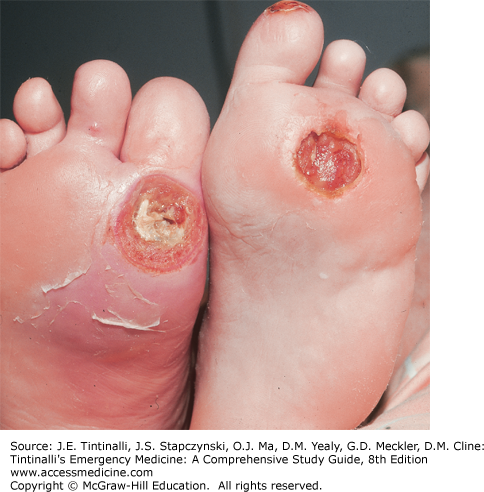

Classic locations for neuropathic ulcers are the plantar surface underlying the first and fifth metatarsal heads, great toe, and heel. Ulcers are usually asymptomatic and “punched out” with a thick rim of surrounding callous (Figure 253-3). However, patients may complain of burning, numbness, itching, or paresthesias. The architecture of the foot is also altered, with flexed toes and prominent metatarsal heads secondary to neuropathy of the intrinsic muscles of the foot. Hypo- or anhidrosis from autonomic impairment may lead to dryness and fissuring of the surrounding skin. The diagnosis is clinical.

Patients with vascular insufficiency should be referred to a vascular specialist for further evaluation. A diabetic foot infection is diagnosed clinically when there are systemic signs of infection, purulence, or multiple signs of local inflammation (redness, warmth, pain, tenderness, or edema).6 Osteomyelitis is suggested by the ability to probe bone with a blunt, sterile, stainless-steel probe and should be confirmed with imaging.

Treatment includes offloading or redistributing the pressure off the wound, maintenance of a moist wound environment, debridement of nonhealing tissue, and treatment of infection. Soft tissue infections can be treated for 7 to 14 days in an outpatient setting with oral cephalosporin, clindamycin, amoxicillin/clavulanate, or fluoroquinolones.7

More severe ulcers or those with associated cellulitis or osteomyelitis require admission and treatment with IV antibiotics for 4 to 6 weeks, such as cefotetan, ampicillin/sulbactam, or clindamycin and a fluoroquinolone. Vancomycin should be given if methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus is suspected. Further discussion is provided in chapter 224, “Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus”; Table 224-4 lists the various cutaneous manifestations of diabetes.

Buruli ulcer is a new emerging disease and the third most common chronic mycobacterial infection in humans after tuberculosis and leprosy.8 Buruli ulcers are rapidly growing ulcers caused by the acid-fast bacillus, Mycobacterium ulcerans. It is usually confined to the tropical areas, with the highest rate in sub-Saharan Africa, but reports have come from subtropical and nontropical nations, including Australia, China, and Japan.9

M. ulcerans is an environmental saprophyte that is present on lush vegetation in swampy areas.10 It infects humans after abrasions come into contact with contaminated soil, water, or vegetation.10 M. ulcerans produces mycolactone, a cytotoxic lipid and necrotizing immunosuppressive polypeptide toxin that induces both apoptotic and necrotic changes in fibroblasts, lipid cells, macrophages, and keratinocytes.11 Buruli ulcers are painless, and it is thought mycolactone damages the peripheral nerves.12

The Buruli ulcer begins as an erythematous nodule approximately 8 weeks after inoculation that eventually ulcerates. The lesions develop on exposed parts of the body, especially on the extremities and face. The resulting painless ulcer has a deep white or yellow necrotic base and undermined edges, as well as edematous surroundings (Figure 253-4). Regional lymphadenopathy and systemic symptoms are minimal to absent. Without treatment, ulcers may spontaneously heal within 6 to 9 months, or they may spread rapidly, causing extensive deformity.

Smears from the base of the ulcer or biopsy specimens should be cultured and examined for acid-fast bacilli. Visible growth by culture requires 6 to 8 weeks, and its success rate is low. Polymerase chain reaction performed on a fresh biopsy is the best method for early diagnosis. Surgical excision is the treatment of choice. Local heating and hyperbaric oxygen also promote healing.13 Antimycobacterial treatment is often ineffective.13 The World Health Organization recommends rifampin and streptomycin dual therapy for 8 weeks. New skin lesions may develop during antimicrobial therapy, and this is known as “paradoxical reactions.”8

Cutaneous leishmaniasis is transmitted by the bite of the sand fly, which is infected by protozoan parasites of the genus Leishmania. In tropical and subtropical regions, leishmaniasis is one of the most common and serious infectious diseases. It is endemic in North Africa, the Mediterranean, the Middle East, India, Central Asia, and Central and South America. Reactivation of latent leishmaniasis can occur in immunosuppressed, human immunodeficiency virus, malnourished, or organ transplant patients.14 There are many varieties of cutaneous leishmaniasis. The typical cutaneous ulcer usually occurs on unclothed skin, is painless, varies in size from 0.5 to 3.0 cm in diameter, and is covered with an exudative crust (Figure 253-5). Diagnosis is clinical but can be confirmed with culture, biopsy, or polymerase chain reaction test. Most lesions heal spontaneously over several months.15

INFLAMMATORY CONDITIONS

Hand and foot dermatitis simply means inflammation of the skin of the hands and/or feet. This nonspecific term is used for several more specific disorders (Table 253-2). The most common causes are contact dermatitis (allergic and irritant), dyshidrosis, and atopic dermatitis. Most contact dermatitis is caused by irritants as opposed to allergens. Atopic dermatitis affects children, usually before 5 years of age, and 2% to 3% of adults.16

Allergic contact dermatitis (poison ivy, poison oak, etc.) Irritant contact dermatitis (soaps, detergents, shoe/glove leather, etc.) Dyshidrosis Atopic dermatitis Dermatophytosis (see Table 253-4) Psoriasis Lichen planus Pityriasis rubra pilaris Palmoplantar keratoderma Autoimmune bullous disease Dermatomyositis Scabies |

Common irritants include soaps, detergents, friction, frequent hand washing, and cold, dry air, resulting in erythema, scaling, and fissuring. Strong irritants like an acid or alkali cause immediate burning, followed by erythema, vesiculation, and bullae formation.

Common allergens include poison ivy/poison oak, nickel, chromate, rubber components of gloves and shoes, dyes in leather and socks, and dichromates used in tanning leather. In acute allergic contact dermatitis, erythema with papules, vesicles, and/or bullae is present. Pruritus is intense, and excoriations are present. Distribution is the most helpful clue to aid in diagnosis. When the hands or feet are involved in allergic contact dermatitis, the eruption tends to be present on the dorsal surfaces, sparing the palms, soles, and web spaces. The thick stratum corneum of the palms and soles prevents penetration of potential allergens. Distribution with linear streaks suggests a plant allergy such as rhus (poison ivy or oak) hypersensitivity (Figure 253-6). Sharp demarcation of footwear indicates a reaction to a component of the patient’s shoes.

Dyshidrosis initially begins as very small, deep-seated, pruritic vesicles on the lateral aspects and the volar surfaces of the palms and soles (Figure 253-7). The dorsal surface of the distal phalanges may also become involved. There is no erythema. Over time, the vesicles may form pustules or desquamate to leave small collarettes of scales. In chronic cases, erythema and scales become more prominent and may be difficult to distinguish from other forms of hand and foot dermatitis.

Atopic dermatitis is part of the “atopic triad” consisting of dermatitis, asthma, and allergic rhinitis.17 Atopic dermatitis of the hands and feet often presents as erythematous, pruritic, scaly patches with prominent involvement of the dorsal surfaces as well as the palms and soles. Chronic atopic dermatitis will also have hyperpigmentation and lichenification and fissuring. Often, other areas of the body are involved. Common areas of involvement include the antecubital and popliteal fossae, posterior neck, and wrists and ankles (Figure 253-8).

The diagnosis is clinical. Differentiating contact dermatitis (allergic and irritant) from dyshidrosis and atopic dermatitis can be extremely difficult. More than one disorder may be present at a time, such as atopic dermatitis complicated by irritant dermatitis. Always consider a fungal infection (see later section “Tinea Pedis and Tinea Manuum”), and a potassium hydroxide preparation can exclude this possibility. A biopsy cannot differentiate between the different types of dermatitis. See Table 253-3 for definitions of terms in superficial cutaneous fungal infections and Table 253-4 for causes of superficial cutaneous fungal infections. Dermatologic consultation is often necessary for specific diagnosis.