Key Clinical Questions

How does the physician approach a patient with multiple comorbidities? How are they different than other patients?

How do multiple comorbidities affect a patient’s prognosis?

How does the physician take prognosis into account when formulating treatment plans for patients?

A 79-year-old woman with moderately severe chronic diseases (obstructive pulmonary disease, osteoporosis, osteoarthritis, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and hypertension) was admitted to the hospital for a complicated urinary tract infection. She had recently moved to the area and needed to establish primary care following discharge. Her newly assigned primary care physician requested that “good maintenance medications” be prescribed for her chronic diseases prior to discharge. However, if the relevant clinical practice guidelines were followed, the patient would be prescribed 12 medications (her cost $406 per month) along with a complicated nonpharmacological regimen (see Table 97-1). The patient did not find these recommendations to be practical. |

| Time | Medications† | Other |

|---|---|---|

| 7:00 am |

|

|

| 8:00 am |

|

|

| 12:00 pm |

| |

| 1:00 pm |

| |

| 7:00 pm |

|

|

| 11:00 pm | Ipratropium metered dose inhaler | |

| As needed | Albuterol metered dose inhaler |

Introduction

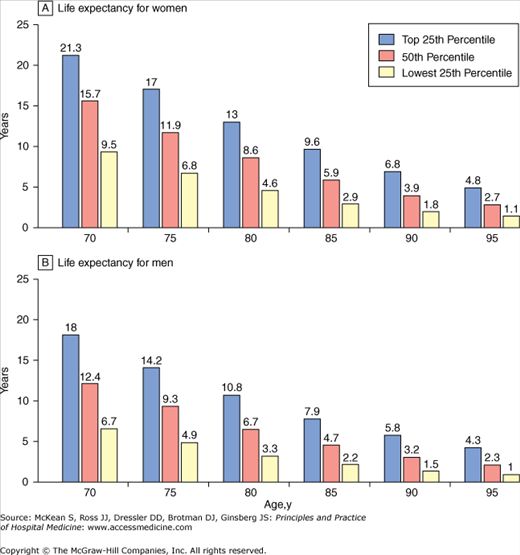

The remarkable success of medicine combined with improved living conditions in the last century has led to an increase in life expectancy in the United States. In the 21st century, a 70-year-old woman in the top 25% percentile of health can expect to live an additional 21.3 years (see Figure 97-1). However, the medical successes that led to this dramatic increase in life expectancy have also created medical challenges. As more people are living into old age, the numbers of patients with multiple comorbitites are rising. In fact, very few patients have only hypertension or simply diabetes; many patients with chronic diseases have multiple comorbidities. In 1999, 48% of Medicare beneficiaries aged 65 years or older had at least three chronic medical conditions and 21% had five or more. Health care costs for individuals with at least three chronic conditions accounted for 89% of Medicare’s annual budget. Comorbidity is associated with higher health care use, physical disability, polypharmacy/adverse drug events, poor quality of life, and increased mortality. Improving care for this population is clearly important, but it is a challenge for physicians, including hospitalists, who need to balance and prioritize treatment of the acute conditions requiring hospitalization with the chronic morbidities that may complicate treatment.

Until recently there have been few guidelines on how to account for patients’ comorbidities and formulate reasonable treatment plans. Many physicians encounter patients as in Case 97-1,—a 79-year-old for whom guideline concordance would result in expensive polypharmacy and potential noncompliance—and might struggle with how to proceed. Consequently, care can be haphazard, scattered, and costly for the patient, provider and health care system. Some argue that the best way to approach the above patient is to consider her prognosis in making recommendations on how to treat her various conditions and take patient preferences into account.

To a large degree, how a medical team decides to treat a patient’s particular condition or comorbidity depends on the patient’s prognosis. “How long do I have?” is among the most common questions asked by patients. Prognosis is defined as “a prediction of the probable course and outcome of a disease” or alternatively, “the likelihood of recovery from a disease.” Current textbooks of internal medicine often give little attention to the prognosis of diseases. The ‘ellipsis of prognosis’ is described by Christakis: “concurrent with a shift in clinical thought from an individual-based to a diagnosis-based conceptualization of disease, prognosis came to be seen as intrinsic to diagnosis and therapy, and explicit attention to prognosis consequently diminished.”

Prognosis guides individualized clinical decisions such as cancer screening or hospice, and identifies groups at high risk for poor outcomes in whom targeted interventions may be most useful. Importantly, prognosis can provide foundation for discussing goals of care. Many patients want to discuss prognosis with physicians, and inadequacy of prognostic information is often the greatest complaint patients/families have about end of life care.

|

Despite the importance of prognosis, physicians are often reluctant to prognosticate. In a national survey of physicians, 90% felt they should avoid being specific about prognosis. Furthermore, 57% felt inadequately trained in prognostication. In another study looking at the accuracy of physician prognostic skill, physicians were asked to provide survival estimates of terminally ill patients at the time of hospice referral. Physicians were accurate 20% of the time and overestimated survival time by a factor of 5.3. In addition, if the duration of the physician-patient relationship increased, prognostic accuracy decreased, suggesting that physician feelings toward patients may alter their ability to prognosticate. In part for this reason, but also because hospitalists often see patients in the midst of a clinical deterioration, it is crucial that hospitalists do not defer prognostication and end-of-life decision making to the outpatient provider.

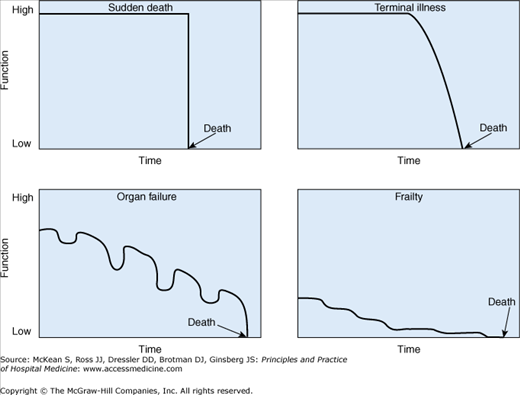

Prognostic Models

Prognostication can be difficult, as there are many different pathways to death (see Figure 97-2). Certain diagnoses, like metastatic cancer, have a more predictable terminal period. However, only 21% of Medicare beneficiaries die of cancer and less than 16% will die suddenly. Many die of acute complications of a chronic condition in which the terminal period is much more uncertain, such as organ failure (20%). Patients who die from dementia or frailty (20%) may have long periods of debility with less predictable courses.