Sexual Abuse and Sexual Assault of Adolescents

V. Jill Kempthorne

In the past several decades, it has become apparent that sexual victimization is widespread both in the United States and abroad. Until recently, efforts to address and prevent sexual abuse and sexual assault have focused primarily on the needs of children and women, and less so on those of adolescents specifically. This may reflect the difficulties in both identifying and understanding adolescent sexual victimization. Adolescents are typified as rebellious, curious, and risk-takers in all aspects of their lives, particularly in their sexual attitudes and behaviors. This will color not only the adolescent’s perception of possible sexual victimization but also societal response to this victimization. Fortunately, this historical bias has been shifting, and the topic of adolescent sexual victimization has received more focused attention in recent years (1,3,4).

To better address key issues, this chapter is organized into five sections: (a) Epidemiologic Considerations, (b) The Unique Vulnerability of the Adolescent, (c) The Clinical Approach to the Adolescent Patient, (d) The Diagnosis and Treatment of Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs), and (e) The Mental and Psychosocial Consequences of Sexual Assault and Sexual Abuse in the Adolescent Patient.

Epidemiologic Considerations

Adolescent sexual victimization is a significant problem. It is estimated that by 18 years of age, 10% to 30% of females and 5% to 10% of males will have been sexually victimized (5). In the 2003 Centers for Disease Control (CDC) Youth Risk Behavior Survey of high-school students, 12% of the female respondents and 6% of the male respondents gave a history of having been forced to have sex (6).

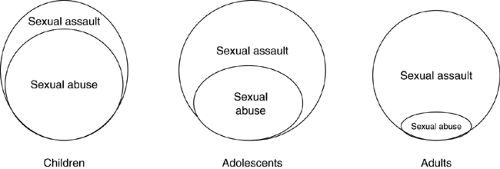

The nature of sexual victimization changes from childhood to adolescence (Fig. 7.1). Younger teens are more commonly the victims of sexual abuse; i.e., victimized by persons in a position of caring for the teen. In fact, sexual abuse most commonly starts in the preteen years. In one study, the risk of sexual abuse increased markedly between the ages of 6 and 10 (7); and in another study, sexual abuse started on average at the age of 7.5 years and continued until the age of 13 (8).

By early to mid adolescence, sexual abuse begins to taper off and sexual assault increases. Older teens are more often the victims of sexual assault and experience violence by intimate partners rather than assault by strangers (9). A 1994 crime data brief from the U.S. Department of Justice reports that almost half the sexual assaults on girls younger than 12 years were by a family member, whereas for girls 12 to 17 years of age this percentage dropped to 20% and, for women 18 and older, to 12% (10). The 1998 National Crime Victimization Survey found that the rate of sexual assault increases through the teen years and peaks at around age 20 (11), supporting the observation that the risk of sexual assault for women is highest during the college years.

These published statistics do not portray the true scope of the problem. First, the relation between sexuality and violence goes beyond the usual definitions

of sexual victimization. In many cases, intimate-partner violence follows rather than precedes sexual intimacy. In an analysis of a national longitudinal study of adolescent health (the AdHealth study), Kaestle and Halpern found that 37% of the respondents had experienced verbal or physical aggression following, not preceding, sexual intercourse (12). Such instances may not be reported as sexual assault, yet they have similar negative effects on the adolescent’s well-being and trajectory of life.

of sexual victimization. In many cases, intimate-partner violence follows rather than precedes sexual intimacy. In an analysis of a national longitudinal study of adolescent health (the AdHealth study), Kaestle and Halpern found that 37% of the respondents had experienced verbal or physical aggression following, not preceding, sexual intercourse (12). Such instances may not be reported as sexual assault, yet they have similar negative effects on the adolescent’s well-being and trajectory of life.

Second, nondisclosure of sexual victimization is extremely common, and most, if not all, surveys and criminal reports have significant underreporting bias. Of those teens surveyed in the 1997 Commonwealth Fund Survey on the Health of Adolescent Girls, 30% of girls and 50% of boys with a history of physical or sexual abuse had told no one (13). In a national telephone survey of children aged 10 to 16 years, Finkelhor found that the rate of sexual assault for 12- to 15-year olds was three times higher than the rate reported in the comparable National Crime Survey (14). In a study of sexual aggression on college campuses, 27% of college women surveyed indicated that they had been victims of sexual assault, yet none had contacted the police (15). In a report on sexual crime statistics, the U.S. Department of Justice cites National Crime Victimization Survey data showing that two thirds of sexual assaults are not reported to law enforcement agencies (16).

Nondisclosure is more common (a) if the victim knows the perpetrator (17), (b) among males than females (13,14,15,16,17,18), and (c) among African American youth (19). Also, for teens who do disclose, delayed disclosure is common. In one study of adolescent girls, a mean time of 2.3 years had elapsed from the initial assault to disclosure (20). In another study of 125 adult sexual assault victims (average age 36 years) receiving care at the sexual assault centers in Maryland, almost 80% had been victimized by a family member, and the average time elapsed to disclosure was 15.5 years (21).

The reasons for nondisclosure or delayed disclosure are many and include the following:

The adolescent’s failure to recognize victimization (22) or the adolescent’s assumption that coercion is a normal part of the sexual experience (23,24). In one study, nearly one third of the adolescents interpreted a scene with violent behavior as love and less than 5% interpreted it as hateful (25).

There are occasions when the adolescent does not remember the assault. Most often this happens if the adolescent is intoxicated. It can also happen if the adolescent has been given the so-called “date-rape drug,” flunitrazepam (Rohypnol), a benzodiazepine with significant sedative and amnesiac effects (26). (See Chapter 12)

The emotional burden of shame, guilt, and fear. These sentiments are common following a date rape, particularly if alcohol or drugs are involved, on college campuses and high schools (17,27,28).

A sense of futility. In one study of adolescents who had not disclosed a history of sexual assault to their parents, half of them thought their parents would not believe them (20).

Fear of the consequences of disclosure, e.g., placement in a foster home, separation from parents or the sexual partner, threats of harm or retribution.

The Unique Vulnerability of the Adolescent

Many of the defining qualities and unique characteristics at the adolescent stage of life may increase the risk of sexual victimization in this age-group, as discussed in the subsequent text.

Adolescent Maturation, Decision-making, and Risk-taking Behavior

Adolescence has been described as maturation in three different domains: physical, cognitive, and psychosocial. The timing and tempo of these maturational changes are important in shaping adolescent sexuality and they vary widely from one child to

the next. Puberty, or the development of secondary sexual characteristics, is an early and mid-adolescent process. It tends to start earlier in girls than in boys and may actually start in the preteen years. In fact, in a recent study involving data from private practice sites, the American Academy of Pediatrics reported that normal girls as young as 8 or 9 years may show pubertal breast development or pubic hair growth (29). Cognitive maturation, or the maturation of abstract reasoning capability, also tends to occur in early and mid adolescence. On the other hand, psychosocial maturation, or the maturation of social relationships and behaviors, extends past the mid adolescent years into late adolescence and sometimes into young adulthood.

the next. Puberty, or the development of secondary sexual characteristics, is an early and mid-adolescent process. It tends to start earlier in girls than in boys and may actually start in the preteen years. In fact, in a recent study involving data from private practice sites, the American Academy of Pediatrics reported that normal girls as young as 8 or 9 years may show pubertal breast development or pubic hair growth (29). Cognitive maturation, or the maturation of abstract reasoning capability, also tends to occur in early and mid adolescence. On the other hand, psychosocial maturation, or the maturation of social relationships and behaviors, extends past the mid adolescent years into late adolescence and sometimes into young adulthood.

Competent decision-making requires a certain degree of cognitive and psychosocial maturity; however, particularly in the early and mid adolescence, this maturity may be lacking. With the appearance of secondary sexual characteristics in the early and mid adolescent years comes a heightened interest in sexual experimentation. Risky sexual behavior can emerge, given a combination of limited life experience, limited self-awareness of sexual feelings, and relatively immature psychosocial skills. This trajectory is seen in studies showing that girls who enter puberty early exhibit more high-risk sexual behavior than girls who enter puberty late (30,31).

Extreme Risk-taking Behavior: Perceived Normalcy and Links to Maltreatment

Although adolescent behaviorists in the early 1900s considered adolescent turmoil and rebellion to be a necessary part of the adolescent experience, recent studies have shown that adolescence is typically not a tumultuous time (32), and that the rate of behavioral disturbance in adolescence is similar to that in the other stages of life (33). Although some risk-taking behavior is essential to adolescent development (34), extreme risk-taking behavior is not. Moreover, extreme risk-taking behavior is not that common in adolescence, contrary to popular perception. A 1993 American Medical Association report on adolescent maltreatment cites numerous studies showing that extreme risk-taking behavior is more common in adolescents who have been abused or neglected and that this behavior itself increases the risk of future maltreatment and victimization (35). This same report states: “Adolescents experience maltreatment at rates equal to or exceeding those of younger children. Recent increases in reported cases of maltreatment have occurred disproportionately among older children and adolescents. However, adolescents are less likely to be reported to child protective services and are more likely to be perceived as responsible for their maltreatment” (35). Perhaps it is too easy for the parents, the neighborhood, or the community to see extreme risk-taking as normal adolescent behavior and to see adolescent maltreatment as a “deserved” consequence of this behavior.

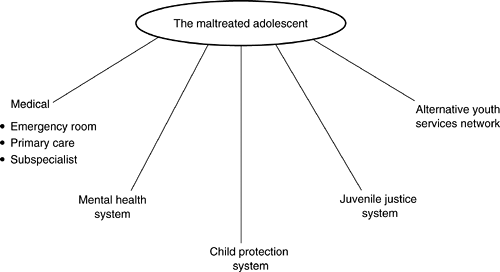

Clearly, there are unique challenges in identifying and addressing adolescent maltreatment. However, there are few, if any, adolescent-focused units as part of child protection. In 1996, a telephonic survey of the 24 county-based child protection offices in the State of Maryland found no evaluation and treatment programs designed specifically to serve maltreated adolescents (E. Kelly, personal communication, 1996). Typically, abused adolescents are served through an array of other programs, as summarized in Figure 7.2.

The Teen–Parent Relationship

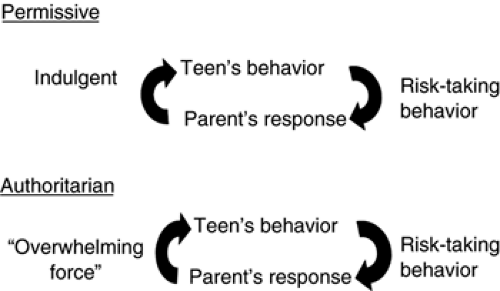

An adolescent’s risk-taking behaviors and the consequences of those behaviors are strongly influenced by family dynamics. The teen–parent relationship that leads to risk-taking behaviors in the first place can lead to escalation of these behaviors (Fig. 7.3). Increased risk-taking behaviors are seen in authoritarian families in response to excessive restriction and discipline and in permissive families in response to lax parental control and “benign neglect.” Also, parents may be the models for the very attitudes and behaviors their teenage children display, and their failure to acknowledge this may contribute to the problem.

Concerns with Confidentiality and Access to Health Care

Several issues limit health care access for adolescent patients and hence increase their vulnerability. Chief among these are concerns about confidentiality. Numerous studies have documented that adolescents may not seek medical care for reproductive health issues if parental consent is required (36,37). Recognizing this, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Academy of Family Physicians, and the American Academy of Obstetricians and Gynecologists have all endorsed the importance of confidentiality in adolescent health care (38,39). In addition, federal law mandates that adolescents have the right to access family planning services, and each state has legislative statutes that allow the provision of reproductive health care services to adolescents without parental consent (40). These “minor consent statutes” were formulated in the 1960s and 1970s after it was recognized that adolescents younger than 18 may self-limit their use of needed reproductive health care services if parental consent is required. These statutes notwithstanding, concerns about confidentiality may determine whether an adolescent decides to seek care following sexual abuse or sexual assault. These concerns are not unfounded. If an adolescent seeks care following sexual abuse, the case must be reported to child protection. If an adolescent seeks care following sexual assault, the provider may feel that it is in the best interest of the adolescent to inform the parent. (See section on the clinical approach to the adolescent patient, in the subsequent text, for further discussion of confidentiality.)

Another issue is whether adolescents have access to health care providers they trust. This is problematic for the teen who sees a particular physician for the first time. How will the teen know whether the provider is comfortable providing confidential care to adolescents? How will the teen decide whether to talk about sensitive sexual health concerns? Can the teen trust the provider to keep these concerns confidential and not tell the parent? Access can also be problematic if the adolescent’s family has been going to the same physician for many years. In such situations, the adolescent may be concerned that the physician will decide that the parents’ need to know is more important than the teen’s need for privacy.

A final issue of access to care is payment for services. This is a problem for both uninsured and insured patients. Adolescents may not understand the importance of health insurance or have the necessary funds to pay for health care out of pocket. If they seek care in an emergency department, problems with insurance and payment may not directly affect their receipt of care, although an itemized bill may be sent to their parents. Parents, in turn, are under no obligation to pay for services that are confidential and provided without their consent, unless the care provided was for an emergency (38,41). If adolescents go to a clinic without active insurance or cash to cover the visit, they are often denied care and referred to an emergency department. This scenario is not infrequent because adolescents and young adults are more likely to be uninsured than individuals from any other age-group (42,43,44).

Even insured adolescents have problems. For adolescents who are covered under their parents’ private insurance, an itemized bill may be sent to the parent following the health care visit. To avoid this, the adolescent may need to arrange to pay for the visit out of pocket. In addition, some private insurers do not pay for family planning. Also, for the adolescent who is on medical assistance, some plans cover family planning services but not the cost of testing and treatment for sexually transmitted diseases.

These health care-access issues are all significant forces shaping the utilization of health care by the adolescent. In many instances, adolescents simply do not go to a physician even though they have significant health care needs. They also may

preferentially use the emergency department for any reproductive health care needs because most emergency departments provide care regardless of insurance coverage.

preferentially use the emergency department for any reproductive health care needs because most emergency departments provide care regardless of insurance coverage.

Legislation has been enacted to address some of the issues of access to health care for the acute sexual assault victim. The Violence Against Women Act of 1994 mandates that states provide forensic examinations free of charge in order to receive federal funds. Despite this, women are sometimes charged for these examinations and are unaware that it should have been free (21).

Increased Vulnerability

Substance Abuse

Many teens abuse drugs and alcohol, and the prevalence increases as the teen grows older. The CDC 2003 Youth Risk Behavior Survey found that more than 75% of high-school students surveyed had consumed alcohol in the past, 37% of high-school seniors had engaged in binge drinking, and 40% of high-school seniors had used marijuana (6). Many studies have shown that substance abuse and coercive sexual experiences commonly occur at the same time (45). In one study of college-aged women, 72% of those who had been raped were intoxicated at the time of the rape (46).

Adolescents with a History of Childhood Sexual Abuse

Adolescents with a history of childhood sexual abuse are at increased risk of early-onset sexual activity, unprotected intercourse, multiple partners, and sexual assault (47,48). One study found that the severity of childhood sexual abuse (e.g., penetration, use of force, frequency of sexual encounter) was directly correlated with the degree of subsequent high-risk sexual behavior (49).

Adolescents Who Are “Cognitively Challenged”

A special group of adolescents at increased risk for sexual victimization are those with developmental disabilities or mental retardation (50,51). Like normal adolescents, these teens often experience a heightened interest in sexuality as they go through puberty. However, they are especially ill equipped to process these feelings because cognitive and psychosocial maturation are both significantly compromised. These teens are more easily coerced into sexual activity but less likely to disclose any sexual experience or seek help if they are confused or scared. Adults need to be alert to changes in their behavior or mood as possible clues to inappropriate or unwanted sexual experiences. An interview may be difficult or impossible once these teens are brought for medical attention, and a complete physical assessment may require conscious sedation (see subsequent text).

An Older Partner: Statutory Rape

Another group at increased risk for sexual victimization are younger adolescents involved with older partners. In state law, the term “statutory rape” is applied to such relationships. Specific details, including the age of the teen and the age difference between the teen and the older partner, differ from one state to the next. For example, in the State of Maryland, statutory rape occurs if the teen is under 16 and the partner is at least 4 years older.

In statutory rape, the risk of coercion or exploitation is high, simply because of the teen’s relative immaturity and the difference in age between the teen and the sexual partner. Yet, these relationships are usually consensual and may provide both emotional and material comforts. Parents may implicitly or explicitly support the relationship as a welcome sign of emerging autonomy and independence.

Statutory rape is not uncommon, although providers and parents may be unaware that it is occurring, especially when the teen and the sexual partner do not appear to be much different in age. Some data suggest that statutory rape is more common with younger teens. A 1988 National Maternal and Infant Health Survey found that fathers of newborn babies were at least 5 years older than the mothers in 24% of births to 17-year olds, 27% of births to 16-year olds, and 40% of births to 14-year-olds (52).

The Clinical Approach to the Adolescent Patient

Including the Parent: When, Why, and How

The adolescent years span a period marked by significant change not only in sexual knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors but also in the teen–parent relationship. The care of the adolescent patient who has been sexually victimized will often involve the parents, and it is therefore important to understand the basic legal rights and responsibilities of both parents and teens and how these change as the teen grows older.

When care is provided to an adolescent patient, it is important to know the parents’ role in the visit. Has the adolescent come to the health care provider alone or with a parent or guardian? Who initiated the visit? Is it the adolescent who wants to be seen or the parent who wants the adolescent to be seen? Does the adolescent have a specific health complaint

or is the adolescent there because the parent has concerns, e.g., does the parent want an examination to see if the adolescent has been sexually active? If the adolescent comes in alone, does the parent know about the visit, or does the teen want everything to be kept confidential? Is the adolescent old enough that any reproductive health concerns, including those following sexual abuse or sexual assault, do not have to be communicated to the parent? Is the adolescent an emancipated minor? The answers to these questions are often not straightforward and will require the provider to consider the specific circumstances and applicable state law.

or is the adolescent there because the parent has concerns, e.g., does the parent want an examination to see if the adolescent has been sexually active? If the adolescent comes in alone, does the parent know about the visit, or does the teen want everything to be kept confidential? Is the adolescent old enough that any reproductive health concerns, including those following sexual abuse or sexual assault, do not have to be communicated to the parent? Is the adolescent an emancipated minor? The answers to these questions are often not straightforward and will require the provider to consider the specific circumstances and applicable state law.

By law, in most states the age of majority is 18. Once the teen has reached this age, parental consent for health care services is not needed, and in most cases he or she must give permission for any sensitive health information to be shared with the parent.

As discussed earlier in this chapter, all states have minor consent statutes that allow the provision of care to adolescents below the age of majority for certain reproductive health care needs, including care for sexual abuse or sexual assault. In addition, in some states, additional statutes apply for the “emancipated minor,” i.e., the adolescent who is below the age of majority and yet considered to be legally autonomous owing to circumstances of life (e.g., is married or is in the armed forces). The emancipated minor may consent for any and all health care, including that needed following sexual assault or abuse.

However, in caring for adolescents, and especially for those who have been sexually victimized, consent does not imply confidentiality. If sexual abuse has occurred, state law mandates reporting the matter to child protection or the police. If statutory rape has occurred, some would argue that the parent has a right to know and an obligation to intercede. In fact, in the State of Maryland, parental failure to intercede knowing that statutory rape has occurred is considered child neglect. If an adolescent under 18 presents to the emergency department following a self-identified coercive sexual assault and does not want the parent to know, the physician may still decide that it is in the best interest of the adolescent to contact the parent. In Maryland, specific legislative statutes give care providers the right (but not the obligation) to share sensitive reproductive health information with the parents of minors.

In all cases, if an adolescent discloses a history of sexual victimization and wants this to be kept confidential, it is important to ask why. The provider must bear in mind that some teens have valid concerns about sharing information with their parents. For example, if there is a nondisclosed history of maltreatment, the teen may justly fear further abuse if the parents are informed of sexual misadventures or victimization. If there is any concern about contacting the parents, then consultation with a social worker is critical to help address these issues and arrange appropriate follow-up care.

Sometimes it will be clear from the very start that the parent should be included in the clinical encounter. At other times, it will not be clear and the provider will have to decide how to involve the parent as the visit unfolds. In general, if the adolescent is brought to the visit by a parent or guardian, the adolescent should be interviewed alone at some point during the course of the visit. Also, if the adolescent is younger than 18, it may be appropriate to ask the guardian or parent about specific concerns they may have. The provider may decide to interview the parent alone at some point. If this happens, it will be important to talk with the teen afterward to allay fears of being talked about “behind their back.” This being said, if the adolescent has been sexually abused, in most cases the parent will need to be involved, and if the adolescent has been sexually assaulted, in most cases the parent should be involved. In all situations, clinical skill, time, and private space are needed to provide the necessary clinical services in an effective manner that balances the parent’s rights and need to know and the adolescent’s rights and need for confidentiality and autonomy.

Obtaining the History

General Considerations

Most adolescent victimization is identified through the history. Sometimes the history is elicited without much difficulty. For instance, the patient presenting to the emergency department following acute sexual trauma may disclose assault or abuse with little prompting. More often, considerable interviewing skill is needed to elicit a history of sexual abuse or assault. The patient may present with vague somatic complaints, depression, or substance abuse and be hesitant to disclose a history of sexual victimization for reasons of guilt, shame, or even fear of retribution. Figure 7.4 details a few of the many medical and psychological consequences of sexual victimization. When a patient presents with these complaints or histories, it is imperative that the care provider ask about sexual victimization.

It is also important to ask about sexual abuse and assault during routine well-child visits. In the 1997 Commonwealth Fund Survey of the Health of American Girls, almost 50% of those who responded felt that their physician should inquire about any history of abuse, yet only 13% reported that their physician had done so (13).

Specific Guidelines

In taking a history from the adolescent patient, the clinician should follow these guidelines:

The history should be obtained with the adolescent fully clothed and comfortable.

Good eye contact should be maintained, and the seating for the examiner and the adolescent should place them at the same eye level.

Note-taking should be limited to minimize distracting the adolescent.

Limits of confidentiality should be discussed, and no promise of unconditional confidentiality should be given.

The teen should be interviewed without the parents present for matters regarding sexuality, a possible history of abuse, and high-risk behaviors.

In approaching the psychosocial interview, the least intimate questions, such as those pertaining to the home, education, and activities, should be asked initially. These can be followed by questions regarding mental health, sexual activity, and abuse.

The sexual history should include the following:

Is there any history of consensual sexual activity?

Age at first experience

Number of lifetime partners

The patient’s sexual orientation

Contraceptive use

Condom use

Age of partners

Use of drugs or alcohol by partner or patient

Any coercive elements in the sexual experience

Is there any history of STIs?

When?

Was the patient treated?

Was the partner treated?

Is there any history of clinical symptoms suggesting an STI?

Penile or vaginal discharge?

Pain with urination?

Abdominal or testicular pain?

Painful sores or wartlike lesions?

For girls, a complete menstrual history should be obtained.

Age at first menses

Menstrual pattern (frequency, duration, regularity)

Any heavy or painful menses

Date of last menstrual period

For girls, is there any obstetric history?

Any prior pregnancy?

Any living children?

Any prior abortions?

Is there any history of sexual abuse or sexual assault?

When did it start and has it stopped?

What was the frequency and degree of sexual contact?

Was force used?

Does anyone know?

Was a report made to child protection or the police?

Has the patient received counseling?

Is the patient safe, or is there risk of further contact with the perpetrator?

Particularly for younger, sexually inexperienced adolescents, a sexual abuse history may be vague. The teen may not remember many details of the experience, or it may not have seemed coercive at the time. The sexually inexperienced female adolescent may not appreciate the difference between vaginal penetration and vulvar coitus, the latter being when

the penis is forced between the labia majora and the labia minora but not past the hymen into the vaginal vault. The patient also may not be able to distinguish between sodomy, or penetration through the anus, from intercrural coitus, whereby the penis is forced between the buttocks but not into the rectum. The patient may not know when ejaculation has occurred. In one study, seminal fluid was detected in 7 of 16 patients who denied vaginal penetration or ejaculation (53).

the penis is forced between the labia majora and the labia minora but not past the hymen into the vaginal vault. The patient also may not be able to distinguish between sodomy, or penetration through the anus, from intercrural coitus, whereby the penis is forced between the buttocks but not into the rectum. The patient may not know when ejaculation has occurred. In one study, seminal fluid was detected in 7 of 16 patients who denied vaginal penetration or ejaculation (53).

The Physical Examination

General Guidelines

With pubertal maturation comes a heightened sense of privacy and increased embarrassment with the physical examination, especially for the younger adolescent. The following guidelines should be used when examining the adolescent patient.

A chaperone should be present whenever possible.

If the adolescent expresses a gender preference for the examiner, it should be accommodated if at all possible.

If the adolescent prefers that the parent be present, this should be accommodated.

If the parent insists on being present, the adolescent should be asked what he or she wants. The adolescent’s preference should be followed if at all possible.

The adolescent should be asked whether he or she has ever had a genital examination. If not, the physician should outline the examination before proceeding.

Appropriate draping should be used, including a gown and a sheet over the lap.

If the adolescent refuses any or all of the genital or perianal examination, gentle counseling may help relieve anxiety. If the adolescent still refuses, the physician may need to outline the need for forensic evidence if the adolescent wants to press charges. If he or she still refuses, the examination cannot be forced on the adolescent.

If failure to do the examination could pose a significant health risk (e.g., failure to diagnose and treat a significant injury), then conscious sedation should be offered.

In the developmentally delayed teen who needs a thorough genital examination, conscious sedation may be necessary so the examination can be performed without traumatizing the teen.

Pubertal Assessment

When examining the breasts and genitalia in the younger adolescent patient, it is important to ascertain whether the child is in early, mid, or late puberty (Tables 7-1 and 7-2). The common approach is to assign Tanner stages. In the late 1960s, Tanner and Marshall studied several thousand school children in England and devised the Tanner classification scheme to describe pubertal changes. For boys, Tanner stages are based on pubic hair characteristics and the size of the testes and the penis. For girls, Tanner stages are based on pubic hair characteristics and breast size and shape. For boys, assigning Tanner stage based on testicular and penis size is difficult because there is considerable individual variability at any given stage. Tanner staging based on pubic hair and breast size and shape is more straightforward.

Table 7.1. Pubertal Timing | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||

Table 7.2. Pubertal Progression (Mean Age at Onset in Years) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

For pubic hair in both boys and girls, staging is as follows:

Tanner 1 prepubertal; no coarse or dark pubic hair

Tanner 2 sparse, slightly coarse pubic hair, not extending onto the mons pubis

Tanner 3 darker, coarser hair extending onto the mons pubis

Tanner 4 more dense hair, covering most of the external genitalia but not extending to the inner thighs

Tanner 5 dense hair extending to the inner thighs

For breast development, staging is as follows:

Tanner 1 prepubertal

Tanner 2 breast bud with minimal breast development beyond the areola

Tanner 3 breast development extending well beyond the areola

Tanner 4 more breast development with elevation of the areola about the breast contour (“the double mound”)

Tanner 5 more breast development with loss of the double mound

In addition to gender differences, there are ethnic differences in pubertal timing. The Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey showed that, in the United States, African American and Mexican American girls enter puberty earlier than Caucasian girls, by 8 and 5 months on average, respectively (54).

The Breast Examination

In girls, especially, it is important to do a breast examination to look for any signs of bruising or other injury. In addition, the breast examination is an important part of Tanner staging. For boys, the breast examination offers little useful information, although gynecomastia should be noted if present. Although this can be seen with testicular tumors and marijuana use, gynecomastia is more typically a normal variation during early to mid adolescence. It happens in up to 50% of adolescent males and usually resolves within 1 year (54). It is important to assure adolescent boys that this is common and normal. This assurance may be especially important for boys who have been sexually molested.

The Female Genital Examination

The primary focus of the female genital examination is the pelvic examination. This examination has three components: the external examination, the speculum examination, and the bimanual examination. The patient should be draped appropriately and examined in the dorsal lithotomy position. The frog-leg position, used for younger patients, does not permit examination of the vaginal vault and the cervix with the speculum and is typically not used in the adolescent patient. Nonlatex gloves should be used whenever possible to avoid latex allergy reactions. If the patient has never had a pelvic examination, it is important to provide an overview of the procedure and show her the speculum before starting the examination.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree