SEIZURES

AMIR A. KIMIA, MD AND VINCENT W. CHIANG, MD

Seizure is the clinical expression of abnormal, excessive, synchronous discharges of neurons residing primarily in the cerebral cortex. This paroxysmal activity is intermittent and its duration may last from a few seconds to many hours. Seizures represent a neurologic emergency either due to the underlying trigger (bleed, infection) or due to potential of the neuronal death, the product of a prolonged seizure. Approximately 5% of children will have at least one seizure in the first 16 years of life. Physicians must have a fundamental knowledge of seizure classification (semiology), all aspects of seizure management (including initial stabilization), determination of cause (differential diagnosis), appropriate definitive treatment, and patient disposition.

BACKGROUND

A seizure is defined as a transient, involuntary alteration of consciousness, behavior, motor activity, sensation, and/or autonomic function caused by an excessive rate and hypersynchrony of discharges from a group of cerebral neurons. A convulsion is a seizure with prominent alterations of motor activity. Epilepsy, or seizure disorder, is a condition of susceptibility to recurrent seizures.

Seizures may be generalized or partial. Generalized seizures reflect involvement of both cerebral hemispheres. These may be convulsive or nonconvulsive. Consciousness may be impaired and this impairment may be the initial manifestation. Motor involvement is bilateral. Types of generalized seizures include absence (petit mal), myoclonic, tonic, clonic, atonic, and tonic–clonic (grand mal) seizures.

Partial (focal, local) seizures reflect initial involvement limited to one cerebral hemisphere. Partial seizures are further classified on the basis of whether consciousness is impaired. When consciousness is not impaired, the seizure is classified as a simple partial seizure. Simple partial seizures may have motor, somatosensory/sensory, autonomic, or psychic symptoms. When consciousness is impaired, the seizure is classified as a complex partial seizure. Both simple and complex partial seizures may evolve into generalized seizures (e.g., jacksonian march). It is important to recognize that generalized seizures with focal manifestations are also considered focal. These manifestations include lateral eye deviation, head tilt, postictal Todd paresis (or paralysis), or psychomotor seizures (also referred to as temporal lobe seizures).

Status epilepticus is a form of prolonged seizure. This is defined as seizures lasting more than 5 minutes or persistent, repetitive seizure activity without recovery of consciousness in between episodes. This is an operational definition of status that guides therapy because only 25% of pediatric seizures last longer than 5 minutes and the longer a seizure persists, the more difficult it becomes to control. If a child is seen in the ED with a reported/witnessed seizure that has resolved, a 30-minute cutoff is used to define status. This definition is used because 30 minutes is when the risk of permanent neuronal injury increases. Status epilepticus is the highest form of seizure emergency.

A postictal (decreased responsiveness) period usually follows a seizure. During this time, the patient may be confused, lethargic, fatigued, or irritable; also, headache, vomiting, and muscle soreness may occur. In general, the length of the postictal period is proportional to the length of the seizure. For brief seizures, there may be few or no postictal symptoms. Transient focal deficits (e.g., Todd paralysis) may occur during the postictal period, but one must first rule out a focal central nervous system (CNS) deficit.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

The underlying abnormality in all seizures is the hypersynchrony of neuronal discharges. Cerebral manifestations include increased blood flow, increased oxygen and glucose consumption, and increased carbon dioxide and lactic acid production. If a patient can maintain appropriate oxygenation and ventilation, the increase in cerebral blood flow is usually sufficient to meet the initial increased metabolic requirements of the brain. This will slow the rate of neuronal loss, which may still occur due to overstimulation. Brief seizures rarely produce any lasting effects. Multiple animal studies and a recent study in humans (FEBSTAT) indicate that 30 minutes of generalized convulsive status epilepticus increases the risk of permanent neuronal injury.

Systemic alterations may occur with seizures and result from a massive sympathetic discharge, leading to tachycardia, hypertension, and initially stress hyperglycemia. Failure of adequate ventilation, especially in patients in whom consciousness is impaired, can lead to hypoxia, hypercarbia, and respiratory acidosis. Patients with impaired consciousness may be unable to protect their airway and are at risk for aspiration. Prolonged skeletal muscle activity can lead to lactic acidosis, rhabdomyolysis, hyperkalemia, hyperthermia, and hypoglycemia.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

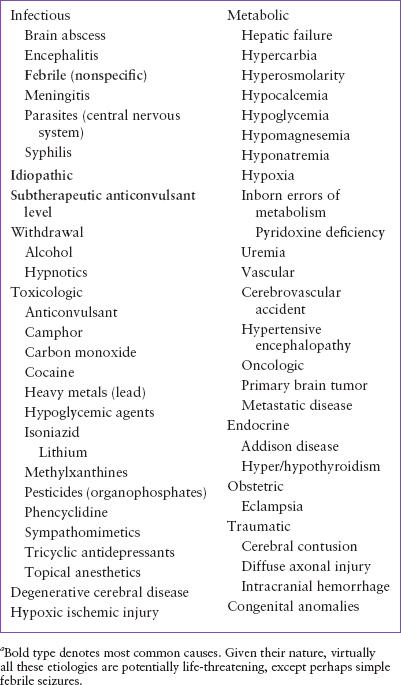

It is important to remember that a seizure does not constitute a diagnosis but is merely a symptom of an underlying pathologic process that requires a thorough investigation (Table 67.1). Often, no underlying condition is identified, and the diagnosis of idiopathic epilepsy is made. However, it is important not to exclude potentially treatable causes prematurely. For instance, seizures that result from metabolic derangements (e.g., hyponatremia, hypoglycemia) are often refractory to anticonvulsant therapy until the abnormality is corrected. Therefore, rapid testing for glucose and sodium are recommended for pediatric status. Furthermore, every effort should be made to rule out a potentially life-threatening cause of seizures (e.g., intracranial injury or hemorrhage, meningitis, ingestions) before a less serious diagnosis is accepted.

TABLE 67.1

ETIOLOGY OF SEIZURESa

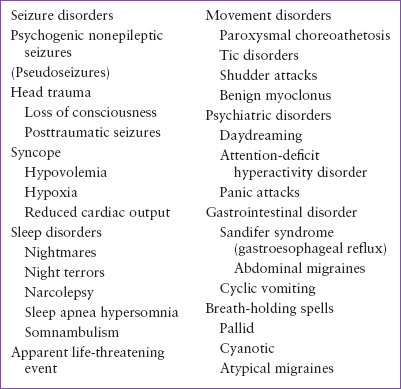

Syncope, or the transient loss of consciousness that results from inadequate cerebral perfusion or substrate delivery, is the most common alternative diagnosis given to patients who present for the evaluation of a seizure episode (see Chapter 71 Syncope). Further complicating matters is the fact that a small percentage of patients with syncope exhibit some sort of convulsive movement. Although vasovagal episodes or orthostatic hypotension is the most common cause for syncope, it is important to evaluate these patients for potential underlying cardiac disease.

Psychogenic nonepileptic seizures (PNES) were formerly called “pseudoseizures.” They are a movement disorder that resembles seizure activity, but have no corresponding abnormal brain electrical activity. PNES include a wide array of conditions ranging from conversion reaction to movement disorder and even parasomnias. When the event is psychogenic in nature, the movements can be quite startling, are typically bizarre and thrashing, and are often associated with a great deal of vocalization. There is usually no biting, incontinence, or injury associated with PNES. In contrast to seizures, PNES are rarely followed by a postictal period or postictal headache, and patients often possess a clear mental status after the event. PNES should also be suspected when the episodes are almost always witnessed or heard and never during sleep, rather than occurring randomly, and if the eyes are closed during the episodes (eyes are closed in less than 10% of actual seizures). In some cases, diagnosis may require long-term video and electroencephalographic (EEG) monitoring. Further complicating the issue is that PNES are most likely to occur in patients with an underlying seizure disorder (Table 67.2).

Breath-holding spells are common, affecting 4% to 5% of all children (see Chapter 134 Behavioral and Psychiatric Emergencies). They typically present between the ages of 6 and 18 months and rarely persist past 5 years of age. The two types of breath-holding spells—cyanotic and pallid—have common features, including a period of apnea and an alteration in the state of consciousness. Usually, some initiating event (e.g., pain, fear, agitation) triggers the episode. The diagnosis is based on the clinical findings, and the prognosis is excellent.

A variety of movement disorders can mimic seizures. Paroxysmal choreoathetosis is often associated with a positive family history for seizures and is exacerbated by intentional movement. Tic disorders can be manifested by twitching, blinking, head shaking, or other repetitive motions. These are usually suppressible and are not associated with any loss of consciousness. Shudder attacks are whole-body tremors similar to essential tremor in adults. Benign myoclonus of infancy can look like infantile spasms but is associated with a completely normal EEG.

Sleep disorders, such as somnambulism, night terrors (preschool-aged children), and narcolepsy (typically in adolescents) can often be diagnosed on the basis of the history alone (see Chapter 134 Behavioral and Psychiatric Emergencies). Infants with gastroesophageal reflux may exhibit torticollis or dystonic posturing (Sandifer syndrome). Atypical migraines and PNES are often diagnosed after other causes are excluded.

TABLE 67.2

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF PAROXYSMAL EVENTS

INITIAL STABILIZATION

This section will focus on patients with generalized convulsive status. The first priority in the seizing patient is to address airway, breathing, and circulation (the ABCs; see Chapter 1 A General Approach to Ill and Injured Children). An adequate airway is necessary to allow for effective ventilation and oxygenation. Patients with impaired consciousness are at risk for obstruction (the tongue, oral secretions, emesis), aspiration (loss of protective reflexes), and hypoventilation. Simple maneuvers such as the jaw thrust or suctioning of the oropharynx may improve the compromised airflow. The use of adjunctive airways (oral or nasopharyngeal) may also help maintain an adequate airway. In patients who are actively seizing, it may be difficult to insert these adjuncts and may cause injury if the intervention is forced. Furthermore, in patients for whom trauma is a possibility, these maneuvers must be undertaken with cervical spine (C-spine) immobilization. In patients in whom the airway remains unstable despite these actions, endotracheal intubation is warranted. When it is necessary to use a muscle relaxant to intubate a seizing patient, one should use the shortest-acting agent possible. The presence of motor activity may be the only clinical manifestation of seizure, and a long-acting muscle relaxant will mask the ongoing seizure activity. One should consider alternatives to succinylcholine in the setting of prolonged seizures because of the potential risk of hyperkalemia related to rhabdomyolysis.

The patient’s circulatory status must also be closely monitored. Seizures generally cause a massive sympathetic discharge that result in hypertension and tachycardia. Continuous monitoring and intravenous (IV) access should be obtained. Blood samples, including rapid blood glucose testing, should be acquired at this time. Peripheral IV access, which is often difficult in the pediatric age group, may be nearly impossible in the actively seizing patient. Intraosseous and/or central venous access may be required in the patient with prolonged seizures.

Once the respiratory and circulatory functions have been assessed and maintained, efforts should be directed at stopping any ongoing seizure activity and making a diagnosis. As long as adequate ventilation and oxygenation are maintained, long-term sequelae are unlikely to result from a transient seizure. Consensus management suggests the initiation of anticonvulsant treatment of anyone who has been seizing for more than 5 minutes. This likely represents all patients who are brought to the ED actively seizing.

EVALUATION AND DECISION

History

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree