CHAPTER 11 Procedural sedation and analgesia

Introduction

Providing effective and safe PSA in the ED is dependent on a number of factors:

Depth of sedation

Four levels of sedation have been defined by the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA):

• Minimal sedation (formerly anxiolysis). This is a state during which patients respond normally to verbal commands. Cognitive function and coordination may be impaired but ventilatory and cardiovascular functions are unaffected.

• Moderate sedation (formerly conscious sedation). This is a state of depressed consciousness during which patients respond purposefully to verbal or light tactile stimulation while maintaining protective airway reflexes. No cardiovascular or ventilatory assistance is required. In order to carry out potentially unpleasant procedures, moderate sedation is generally the goal.

• Deep sedation. This is a level of consciousness during which patients are not easily aroused and may need airway and/or ventilatory assistance. They may respond purposefully to repeated or painful stimulation. Cardiovascular function is usually maintained.

• General anaesthesia. This is a state of drug-induced loss of consciousness in which patients are not arousable and therefore require intervention for airway protection. They often have impaired cardiorespiratory function needing support.

How to perform PSA

• An increased chance of successful completion of the intended procedure (although PSA does not necessarily guarantee that the procedure will not fail!).

7. Can ketamine, midazolam, fentanyl, propofol and etomidate be safely administered to adults and children by emergency physicians in the ED?

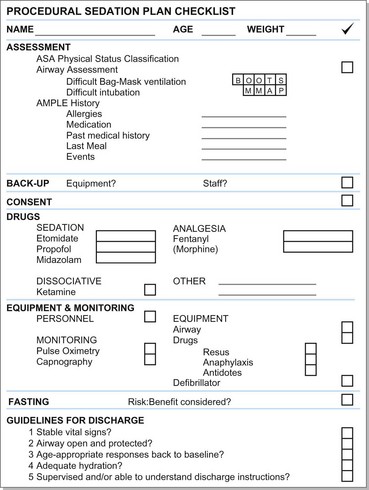

So where do we start and how do we apply this in creating a plan for PSA? It’s as easy as ABC (Fig. 11.1):

Assessment

ASA physical status classification

The ASA stratifies patients who will be undergoing anaesthesia according to a physical status classification (Table 11.1).

Table 11.1 ASA physical status classification

| Class 1 | Normally healthy patient |

| Class 2 | Mild systemic disease |

| Class 3 | Severe systemic disease, but not incapacitating |

| Class 4 | Severe systemic disease that is a constant threat to life |

| Class 5 | Moribund, not expected to survive without the procedure |

Airway assessment

A useful aide-mémoire to recall the potential causes of difficult bag–mask ventilation is BOOTS.

The mnemonic MMAP can be used to assess the patient’s anatomy for possible difficult laryngoscopy.

Mallampati score. Class I and II generally correlate with easy direct laryngoscopy, while III and IV with difficult laryngoscopy.

Measurements 3-3-1. Likely intubation difficulty can be envisaged if the patient can fit less than 3 of their own fingers in the hyomental area; less than 3 fingers between their upper and lower teeth (mouth opening); and has less than 1 cm of jaw protrusion (the ability to protrude the lower teeth anterior to the upper teeth).

Atlanto-occipital extension. If cervical spine precautions are not required, assess the patient’s ability to flex the neck at the lower part of the cervical spine and extend the head on the upper cervical spine. (PSA should not be performed on a patient with a potential cervical spinal injury except under exigent circumstances.)

AMPLE history

The AMPLE mnemonic is useful in your initial patient assessment.

Allergies. It is important to enquire about allergies to medication and/or previous adverse events when the patient has been sedated or undergone anaesthesia.

Medication. Medication that is currently being used must be established. Both allopathic and homeopathic medications may cause drug interactions. The use of chronic medication can reveal a diagnosis that may not have been mentioned previously. Also check whether the patient has taken/been given analgesia/other medication for the current problem prior to hospital arrival.

Past medical history. This would have hopefully been covered in the initial patient evaluation but serves as a reminder.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree