CHAPTER 152

Ring Removal

Presentation

A ring has become tight on the patient’s finger after an injury (usually a sprain of the proximal interphalangeal [PIP] joint) or after some other cause of swelling, such as a local reaction to a bee sting. Sometimes, chronic tight-fitting rings begin to obstruct lymphatic drainage, causing swelling and further constriction (Figure 152-1). The patient usually wants the ring removed even if it requires cutting the ring off, but occasionally, a patient has a very personal attachment to the ring and objects to its cutting or removal.

Figure 152-1 Tight-fitting ring with secondary lymphatic obstruction and swelling.

What To Do:

Immediately recognize vascular insufficiency, amputation, motor or sensory compromise, and other important injuries distal to the ring.

Immediately recognize vascular insufficiency, amputation, motor or sensory compromise, and other important injuries distal to the ring.

Limit further swelling by applying ice and elevating the extremity.

Limit further swelling by applying ice and elevating the extremity.

When a fracture is suspected, order appropriate radiographs, either before or after removing the ring.

When a fracture is suspected, order appropriate radiographs, either before or after removing the ring.

With substantial injuries, a digital or, preferably, a metacarpal block might be necessary to allow comfortable removal of the ring.

With substantial injuries, a digital or, preferably, a metacarpal block might be necessary to allow comfortable removal of the ring.

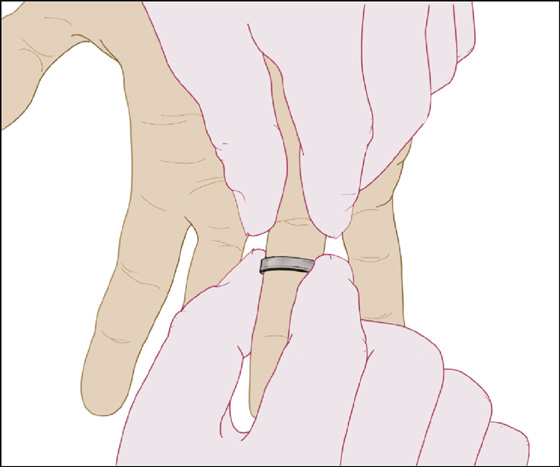

In most cases, lubrication with soap and water or a water-soluble lubricant, along with proximal traction on the skin (thereby drawing the skin taut beneath the ring), is enough to help the ring twist off the finger (Figure 152-2). Grasping the ring after covering it with a gauze sponge may give you greater traction. A large, threaded metal nut can simply be unscrewed after lubricating the finger.

In most cases, lubrication with soap and water or a water-soluble lubricant, along with proximal traction on the skin (thereby drawing the skin taut beneath the ring), is enough to help the ring twist off the finger (Figure 152-2). Grasping the ring after covering it with a gauze sponge may give you greater traction. A large, threaded metal nut can simply be unscrewed after lubricating the finger.

Figure 152-2 Pull skin taut and twist ring off.

If this simple method is not successful, consider several other techniques that preserve the ring. (With rare exceptions, these techniques can be performed with 2.0 to 3.0 silk, umbilical tape, Penrose drains, phlebotomy tourniquets, or other similar available items.)

If this simple method is not successful, consider several other techniques that preserve the ring. (With rare exceptions, these techniques can be performed with 2.0 to 3.0 silk, umbilical tape, Penrose drains, phlebotomy tourniquets, or other similar available items.)

Exsanguination of the digit: Exsanguinate the finger by applying a tightly wrapped spiral of Penrose drain or flat rubber phlebotomy tourniquet tape around the exposed portion of the finger, elevate the hand above the head, wait 15 minutes, and then inflate a blood pressure cuff to 50 to 75 mm Hg above the patient’s systolic pressure as a tourniquet around the upper arm above the exsanguinated finger (Figure 152-3). Wrap the cuff with cotton cast padding to keep the Velcro connection from separating, and clamp the tubing to prevent a slow air leak. Remove the tight rubber wrapping from the finger, and, leaving the arm tourniquet in place and inflated, again attempt to twist the ring off using lubrication. If necessary, this procedure may be repeated several times until the swelling is adequately reduced.

Exsanguination of the digit: Exsanguinate the finger by applying a tightly wrapped spiral of Penrose drain or flat rubber phlebotomy tourniquet tape around the exposed portion of the finger, elevate the hand above the head, wait 15 minutes, and then inflate a blood pressure cuff to 50 to 75 mm Hg above the patient’s systolic pressure as a tourniquet around the upper arm above the exsanguinated finger (Figure 152-3). Wrap the cuff with cotton cast padding to keep the Velcro connection from separating, and clamp the tubing to prevent a slow air leak. Remove the tight rubber wrapping from the finger, and, leaving the arm tourniquet in place and inflated, again attempt to twist the ring off using lubrication. If necessary, this procedure may be repeated several times until the swelling is adequately reduced.

Figure 152-3 Tourniquet technique.

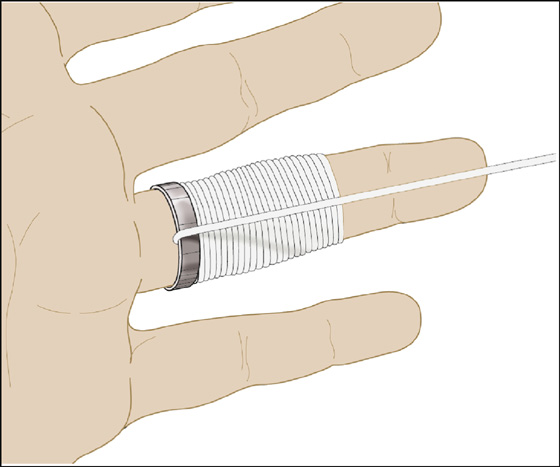

String wrap or string pull technique: A technique that tends to be rather time consuming and only moderately effective (but one that can be readily attempted in the field) is the string wrap or coiled-string technique. Slip the end of a string (kite string is good) under the ring and wind a tight single-layer coil down the finger, compressing the swelling as you go. Pull up on the end of the string under the ring; then slide and wiggle the ring down over the coil (see Figure 152-4).

String wrap or string pull technique: A technique that tends to be rather time consuming and only moderately effective (but one that can be readily attempted in the field) is the string wrap or coiled-string technique. Slip the end of a string (kite string is good) under the ring and wind a tight single-layer coil down the finger, compressing the swelling as you go. Pull up on the end of the string under the ring; then slide and wiggle the ring down over the coil (see Figure 152-4).

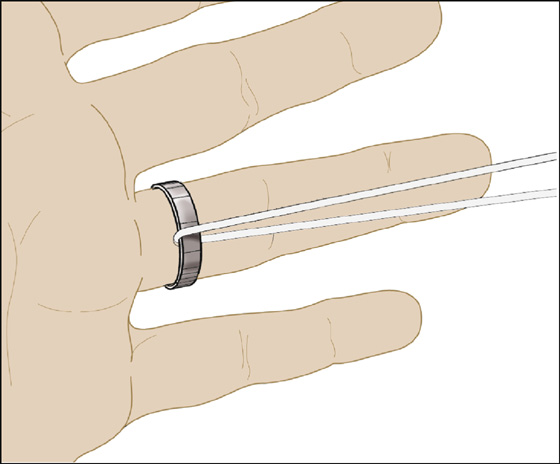

Another associated technique is to pull a length of string under the ring using a hemostat and then tie it into a large loop that can be placed around the clinician’s wrist. This will allow traction to be applied, and the string will slide around and around the circumference of the ring as it is pulled, using lubricant, as mentioned previously. A small lubricated Penrose drain may be substituted for string (see Figure 152-5).

Another associated technique is to pull a length of string under the ring using a hemostat and then tie it into a large loop that can be placed around the clinician’s wrist. This will allow traction to be applied, and the string will slide around and around the circumference of the ring as it is pulled, using lubricant, as mentioned previously. A small lubricated Penrose drain may be substituted for string (see Figure 152-5).

If the ring is still unable to be removed with these techniques, and there is the potential for vascular compromise, the ring will need to be cut off. (Also, cut the ring if the patient endorses this approach or if there is significant distal injury or too much pain with the other techniques.) Inform the patient that a jeweller should be able to repair the band after removal.

If the ring is still unable to be removed with these techniques, and there is the potential for vascular compromise, the ring will need to be cut off. (Also, cut the ring if the patient endorses this approach or if there is significant distal injury or too much pain with the other techniques.) Inform the patient that a jeweller should be able to repair the band after removal.

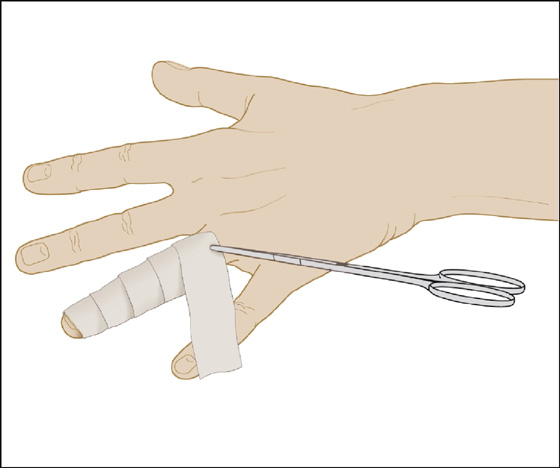

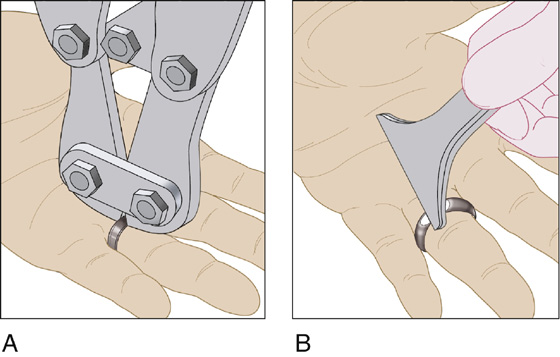

A standard ring cutter can be used to cut through a narrow ring band. Bend the ring apart with pliers or hemostats placed on either side of this “saw cut” to allow removal (Figure 152-6).

A standard ring cutter can be used to cut through a narrow ring band. Bend the ring apart with pliers or hemostats placed on either side of this “saw cut” to allow removal (Figure 152-6).

Figure 152-4 String technique.

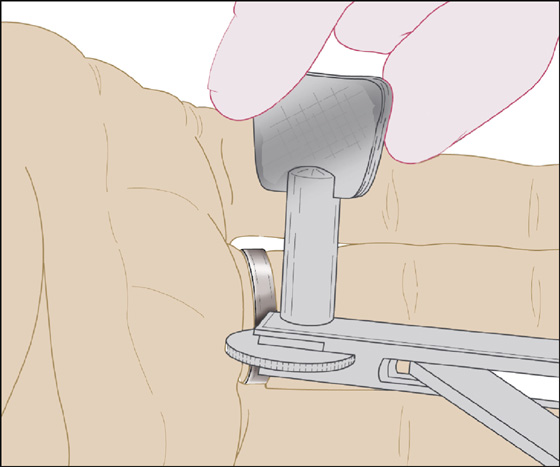

If the band is wide or made of hard metal, it will be much easier to cut out a 5-mm wedge from the ring using an orthopedic pin cutter (Figure 152-7, A). Take a cast spreader, place it in the slot left by the removal of the wedge, and spread the ring open (Figure 152-7, B). Alternatively, two cuts may be made on opposite sides of the ring, allowing it to be removed in halves.

If the band is wide or made of hard metal, it will be much easier to cut out a 5-mm wedge from the ring using an orthopedic pin cutter (Figure 152-7, A). Take a cast spreader, place it in the slot left by the removal of the wedge, and spread the ring open (Figure 152-7, B). Alternatively, two cuts may be made on opposite sides of the ring, allowing it to be removed in halves.

Figure 152-5 String-loop technique.

Another useful device for removing constricting metal bands is the Dremel Moto-Tool, with its sharp-edged grinder attachment. Protect the underlying skin with a heat-resistant shield. If a dental drill is available, it can also cut steel. Motorized commercial ring cutters are also available (Vigor Electric Ring Cutter, http://www.rainbowsupply.com).

Another useful device for removing constricting metal bands is the Dremel Moto-Tool, with its sharp-edged grinder attachment. Protect the underlying skin with a heat-resistant shield. If a dental drill is available, it can also cut steel. Motorized commercial ring cutters are also available (Vigor Electric Ring Cutter, http://www.rainbowsupply.com).

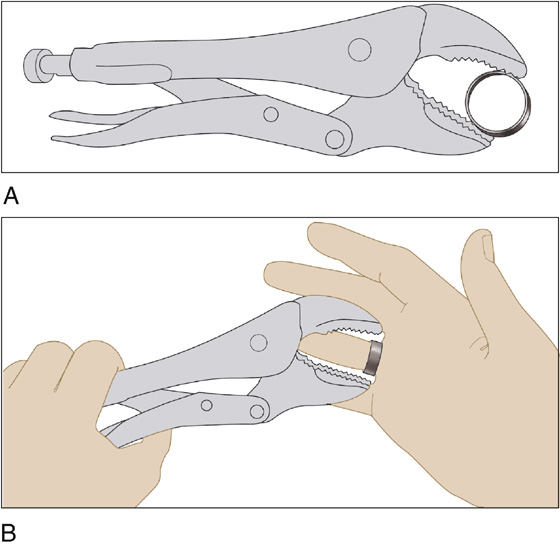

For hard metal (tungsten carbide) or ceramic finger rings that cannot be twisted off, attempt removal by cracking them into pieces using a standard vice grip–style locking pliers (Figure 152-8). Place the locking pliers over the ring and adjust the jaws to clamp lightly. Release and adjust the tightener one-third turn and then clamp again. Repeat until a crack is heard; then continue clamping in different positions until the hard material breaks away. Return the larger pieces to the patient, because they may be able to receive a replacement ring from the manufacturer.

For hard metal (tungsten carbide) or ceramic finger rings that cannot be twisted off, attempt removal by cracking them into pieces using a standard vice grip–style locking pliers (Figure 152-8). Place the locking pliers over the ring and adjust the jaws to clamp lightly. Release and adjust the tightener one-third turn and then clamp again. Repeat until a crack is heard; then continue clamping in different positions until the hard material breaks away. Return the larger pieces to the patient, because they may be able to receive a replacement ring from the manufacturer.

Figure 152-6 Ring-cutter technique.

Figure 152-7 A and B, Orthopedic pin-cutter technique.

Figure 152-8 A and B, Vice grip–style locking pliers are used to crack tungsten carbide or ceramic rings. (Adapted from Hajduk SV: Letter to the editor: emergency removal of hard metal or ceramic finger rings. Ann Emerg Med 37:736, 2001.)

For a child who sticks a finger into a round hole in a plastic toy, sports helmet, or other plastic product and becomes entrapped, release the finger by first cutting around the hole using a standard orthopedic cast cutter. This will allow the patient’s finger to be released from the large plastic object, leaving a plastic ring around the patient’s freed finger. This smaller object can now be removed using any of the earlier techniques or by just protecting the underlying skin and using the cast cutter to cut this plastic ring in half.

For a child who sticks a finger into a round hole in a plastic toy, sports helmet, or other plastic product and becomes entrapped, release the finger by first cutting around the hole using a standard orthopedic cast cutter. This will allow the patient’s finger to be released from the large plastic object, leaving a plastic ring around the patient’s freed finger. This smaller object can now be removed using any of the earlier techniques or by just protecting the underlying skin and using the cast cutter to cut this plastic ring in half.

What Not To Do:

Do not insist that a ring must be cut off when a patient requests that the ring not be removed, if the patient is expected to have only transient swelling of the hand or finger and there is no evidence of any vascular compromise of the affected finger. If the patient is vigilant and reliable, he can be warned of the signs of vascular compromise (pallor, cyanosis, pain, and/or increased finger swelling) and instructed to keep his hand elevated above the level of his heart and to apply cool compresses. He should then be made to understand that he is to return for further care if the circulation becomes compromised, because of the possible risk of losing his finger. Be understanding, and document the patient’s requests and the directions given to him.

Do not insist that a ring must be cut off when a patient requests that the ring not be removed, if the patient is expected to have only transient swelling of the hand or finger and there is no evidence of any vascular compromise of the affected finger. If the patient is vigilant and reliable, he can be warned of the signs of vascular compromise (pallor, cyanosis, pain, and/or increased finger swelling) and instructed to keep his hand elevated above the level of his heart and to apply cool compresses. He should then be made to understand that he is to return for further care if the circulation becomes compromised, because of the possible risk of losing his finger. Be understanding, and document the patient’s requests and the directions given to him.

Discussion

The constricting effects of a circumferential foreign body can lead to obstruction of lymphatic drainage, which, in turn, leads to more swelling and further constriction. Eventually, venous and arterial circulation is compromised. If it is believed that these consequences are inevitable, be direct with the patient about having the ring removed.

Hair-thread tourniquets can become tightly wrapped around an infant’s finger, toe, or penis, causing swelling, ischemia, or discoloration distal to the band (Figure 152-9). Removing this constricting band of one or more fibers can be quite difficult. It usually requires local anesthesia, dissection, and severing of the deeply embedded fibers with a large-gauge needle and magnifying loupes. Another technique is to use lysis by a depilatory agent, such as Nair or Neet. By applying hair remover to the hair tourniquet, the constricting bands may be lysed within 10 to 15 minutes. Even when the constricting bands appear to be completely released, provide for a wound check within 24 hours.

Figure 152-9 Hair tourniquet with distal venous and lymphatic engorgement on the second toe of a toddler.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree