Rheumatologic

23-1 Rheumatoid Arthritis

Robert Hendrickson

Clinical Presentation

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) affects less than 1% of the U.S. population1 and most commonly occurs in women aged 40 to 70 years.2 Patients may present to the emergency department (ED) without a diagnosis of RA but with new joint swelling and pain. In early RA, patients typically complain of progressive stiffness and symmetric involvement of multiple joints over a period of weeks to months. Additional symptoms may include fever, malaise, and fatigue.2 On examination, findings of affected joints may range from minimal signs of inflammation to erythematous, tender, effusion-filled joints with limited range of motion.

Patients with an established diagnosis of RA may present with exacerbations of their disease, extraarticular symptoms, or side effects of their medications. Extraarticular symptoms include rheumatoid nodules, keratoconjunctivitis, iritis, sicca, pleural effusions, myocarditis, pericarditis, pulmonary fibrosis, cardiac valvular nodules, mononeuritis, hepatitis, anemia, leukocytosis, splenomegaly, and vasculitis.2 Side effects of the various medications used to treat RA can be significant. They include renal failure, gastrointestinal bleeding, and cytopenias with nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs); retinopathy with antimalarial agents; hepatitis with sulfasalazine; myelosuppression and diarrhea with gold; thrombocytopenia with D-penicillamine; infection and edema with corticosteroids; pancytopenia and hepatic fibrosis with methotrexate; pancytopenia with azathioprine; interstitial nephritis with cyclophosphamide; renal insufficiency, anemia, and hypertension with cyclosporine; and hepatitis with leflunomide.1,3

FIGURE 23-1 Felty’s syndrome: rheumatoid arthritis, granulocytopenia, splenomegaly, and lower-extremity ulcers. (From Sontheimer, with permission.) |

The symptoms of RA may be slowly progressive, or patients may have relatively symptom-free baseline function with intermittent exacerbations of disease.3 During inflammatory exacerbations, laboratory markers may be present, such as elevations of the leukocyte (white blood cell [WBC]) count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein, and rheumatoid factor.

Pathophysiology

RA is an autoimmune disorder that is characterized by symmetric stiffness, swelling, and pain in peripheral joints.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis usually is based on typical clinical features of stiffness, swelling, and pain in peripheral (distal) joints and is confirmed with laboratory tests and biopsy of synovial tissue. Consultation with a rheumatologist or primary care physician to direct testing and arrange for close follow-up may be prudent.

Clinical Complications

Most patients experience a chronic, progressive, fluctuating course.1 Joint inflammation and destruction causes significant morbidity. After 10 years with RA, 50% of patients are unable to work.3 Significant complications may occur secondary to extraarticular involvement or from side effects of the medications used to treat the disease.

Management

Patients with a possible new diagnosis of RA synovitis may be treated with NSAIDs and other pain medications. They should then be thoroughly evaluated by a primary care physician or rheumatologist as soon as possible, because early initiation of additional antiinflammatory medications (e.g., corticosteroids, methotrexate) may decrease joint destruction.1,2 Patients with an exacerbation of chronic RA may require increases in antiinflammatory medications. Extraarticular symptoms may be managed with antiinflammatory drugs and organ-specific therapy (e.g., thoracentesis for pleural effusion).

REFERENCES

1. American College of Rheumatology Subcommittee on Rheumatoid Arthritis guidelines. Guidelines for the management of rheumatoid arthritis: 2002 update. Arthritis Rheum 2002;46:328-346.

2. Lee DM, Weinblatt ME. Rhematoid arthritis. Lancet 2001;358:903-911.

3. Brooks PM. Clinical management of rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet 1993;341:286-290.

4. Choy EH, Panayi GS. Cytokine pathways and joint inflammation in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med 2001;344:907-916.

23-2 Osteoarthritis

Robert Hendrickson

Clinical Presentation

Osteoarthritis (OA) typically causes joint pain that is exacerbated by activity and stiffness in the morning or after inactivity.1 The joint may appear normal or have mild signs of inflammation or effusion. Systemic signs are absent. The joint is generally tender to palpation and may have bony enlargement, crepitus on movement, and limited range of motion.1

Pathophysiology

OA is local inflammation of the articular cartilage and subchondral bone resulting from mechanical stress.1

A variety of factors, including genetic, biochemical, and inflammatory factors, contribute to the destruction of synovial cartilage and inflammation of subchondral bone.1

Diagnosis

OA may be diagnosed by noting the typical history and physical examination.

Clinical Complications

The main complications of OA are decreases in mobility and in performance of activities of daily living.

Management

Initial treatment of OA involves nonpharmacologic therapy, including weight loss (if overweight), aerobic exercise, range-of-motion exercises, and quadriceps-strengthening exercises. Initial pharmacologic therapy for all patients with OA is acetaminophen. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitors may be added to acetaminophen but should not substitute for acetaminophen, because NSAIDs are no more effective and have significant side effects. Tramadol or another opioid may be used for temporary relief of pain. Other adjunctive therapies that may be efficacious are topical anesthetics (e.g., methyl salicylate, capsaicin) and glucosamine/chondroitin. Intraarticular corticosteroids may decrease pain from OA and are an excellent option in patients who are at significant risk for side effects of NSAIDs (gastrointestinal bleeding). However, intraarticular corticosteroids should not be used if there may be an infection in the joint.1

REFERENCES

1. Recommendations for the medical management of osteoarthritis of the hip and knee: 2000 update. American College of Rheumatology Subcommittee on Osteoarthritis Guidelines. Arthritis Rheum 2000; 43:1905-1915.

23-3 Septic Arthritis

Robert Hendrickson

Clinical Presentation

Patients with septic arthritis (SA) typically present with an acutely painful, warm, and swollen single large joint (80% to 90% of cases).1,2 Joints most commonly affected are those with recent manipulation (e.g., arthroscopy, surgery), prosthetic joints, and those with chronic inflammation (e.g., osteoarthritis [OA], rheumatoid arthritis [RA]).2 SA may occasionally be polyarticular (10% to 20%) and most commonly affects the large joints, particularly the knees (50%).2 Patients may develop fever, chills, joint effusion with swelling, redness, and tenderness of the joint space. Patients with an infection of a prosthetic joint may complain only of pain, with fever and erythema being much less common.2

Diagnosis

The diagnosis may be presumed in patients with typical symptoms and confirmed with arthrocentesis. Synovial fluid should be examined with Gram staining (positive in 60% to 80% of cases), cell count (white blood cell [WBC] count typically greater than 50,000 cells/hpf), differential count (predominance of polymorphonuclear neutrophils [PMNs]), crystals (to rule out crystal arthropathies, if suspected), and culture (positive in 50%).1,2 In patients in whom gonococcal arthritis is suspected (young, healthy, sexually active adults), mucosal swabs (cervical, urethral, pharyngeal, or rectal) should be obtained for identification of Neisseria gonorrheae.

Pathophysiology

Bacterial arthritis may be caused by hematogenous spread from an infected organ (e.g., cervix, urethra, kidney, pharynx, lung) or by direct inoculation (e.g., after surgery, puncture wound). Hematogenous spread most commonly occurs in patients with impaired immune responses (e.g., diabetes mellitus, RA, renal failure, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome) and those with damage or inflammation of the joints (OA or RA). Bacterial infection of the synovium leads to an inflammatory cascade within the joint. In 80% of the cases, the bacteria are gram-positive aerobes (Staphylococcus aureus, β-hemolytic streptococci, or Streptococcus pneumoniae), and in 20% they are gram-negative bacilli (Escherichia coli, Haemophilus influenzae).1,2

Clinical Complications

Untreated bacterial arthritis may lead to destruction of the joint space (25% to 50%), as well as systemic infection.2

Management

Patients with nongonococcal bacterial septic arthritis should be admitted to the hospital and treated with a parenteral dose of a third-generation cephalosporin (ceftriaxone or cefotaxime).1 Antibiotics may be based on Gram staining of the synovial fluid if this test is rapidly available. Consultation with an orthopedist should be considered, because daily arthrocentesis or surgical débridement may be necessary. Patients with infected prostheses may require removal of the prosthetic joint after initiation of antibiotic therapy and should be cared for by an orthopedist.

REFERENCES

1. Garcia-De La Torre I. Advances in the management of septic arthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 2003;29:61-75.

2. Goldenberg DL. Septic arthritis. Lancet 1998;351:197-202.

23-4 Pseudogout

Robert Hendrickson

Clinical Presentation

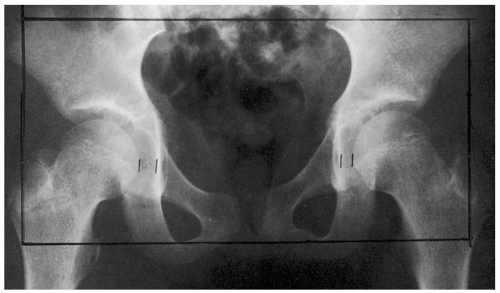

Pseudogout may manifest as an acute monoarticular or oligoarticular arthritis with erythema, pain, swelling, and fever. The most frequently affected joints are the knees, wrists, shoulders, and hips.1 Calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate deposition disease (CPPD) may be asymptomatic, or it may be found in association with osteoarthritis (OA). Radiographic findings include “hook-like” osteophytes, cystic changes, and chondrocalcinosis.1

Pathophysiology

Pseudogout, also called CPPD, is an inflammatory arthropathy that is caused by deposition of calcium-containing crystals in joints.

CPPD is dependent on genetic, metabolic, and endocrine influences.1 Risk factors include older age, family history, hyperparathyroidism, hypomagnesemia, hemochromatosis, and hypophosphatemia. Synovial crystal formation leads to an inflammatory cascade, synovial hyperplasia, and collagenase production.1

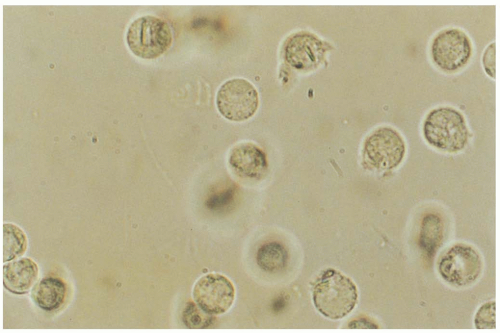

Diagnosis

The clinical presentation may mimic that of OA, rheumatoid arthritis (RA), septic arthritis, or gout. Typical radiographic findings (e.g., chondrocalcinosis) and arthrocentesis findings may differentiate this disorder from gout and septic arthritis (SA). The synovial white blood cell (WBC) count is typically 10,000 to 20,000 cells/hpf in pseudogout, and calcium-containing crystals can be visualized by regular microscopy.1 Crystals may be extracellular or intracellular or both, and they are weakly positively birefringent.

Clinical Complications

Complications include pain and joint destruction with limitation of function.

Management

Treatment of acute pseudogout episodes include arthrocentesis and oral nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).1 Colchicine and intraarticular corticosteroids are effective but are generally reserved for patients with refractory disease. Long-term prophylactic therapy may include NSAIDs, colchicine, and oral corticosteroids.1

REFERENCES

1. Agudelo CA, Wise CM. Crystal-associated arthritis in the elderly. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 2000;26:527-546.

23-5 Gout

Robert Hendrickson

Clinical Presentation

Patients with a first gouty episode typically present with acute onset of monoarticular arthritis (85%). Sixty percent of cases involve the first metatarsal joint.2 The joint and surrounding tissues are typically erythematous, edematous, and warm, making differentiation of gout from septic arthritis (SA) somewhat difficult. As the disease progresses, patients may present to the emergency department (ED) with polyarticular arthritis with fever and constitutional symptoms. Urate deposits located beneath the skin (tophi) may also develop, particularly on the elbows and fingers.2 Before the age of 60 years, gout has a male predominance; however, rates of disease are equal in elderly men and women. Older patients also have more atypical presentations. Older patients are more likely to have polyarticular arthritis, arthritis of the small hand joints, and development of tophi early in their disease.2

Pathophysiology

Gout is a clinical syndrome of articular inflammation caused by elevated concentrations of urate (monosodium urate monohydrate), with resulting precipitation of crystals in joints.1

The risk of developing gout is related to genetic and environmental factors and directly proportional to the serum urate concentration.1,3 Although most people with elevated urate concentrations do not have gout, some form urate crystals within synovial cavities. These crystals are phagocytized by macrophages, initiating an inflammatory cascade that attracts more inflammatory cells to the joint and surrounding tissue.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis can be suspected with a typical clinical history (e.g., middle-aged male with acute onset of monoarticular arthritis in the first metatarsal joint without fever or lymphangitis). A definitive diagnosis of gouty arthritis may be made with the identification of urate crystals in joint fluid or tissue.2 Urate crystals may be visible as needle-shaped crystals within white blood cells on typical microscopy, but they are best identified with a polarizing microscope (negative birefringence).2

Patients with gout are thought to have increased intake, overproduction and/or a decreased excretion of urate, or some combination of these.1 Urate is a metabolic product of purine metabolism. Ingestion of foods with high purine concentrations (e.g., beer, meat, beans, peas, spinach)1 or conditions that increase cellular turnover (e.g., cancer, inflammatory conditions) may contribute to elevated urate concentrations. Additionally, most patients with gout have decreased renal clearance of urate, secondary to renal insufficiency or use of medications that decrease excretion (e.g., loop or thiazide diuretics, pyrazinamide, didanosine, ethambutol, niacin).1

Clinical Complications

Gout may produce debilitating episodes of arthritis. In addition, cosmetically problematic and potentially deforming tophi may develop.

Management

Patients who present with a mild acute gouty episode may be treated with nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitors

on an outpatient basis, with follow-up with their primary doctor or rheumatologist.2,3 Although it is not necessary to perform arthrocentesis in patients with a typical history and physical examination, arthrocentesis should be considered in any patient if there is any concern for SA.

on an outpatient basis, with follow-up with their primary doctor or rheumatologist.2,3 Although it is not necessary to perform arthrocentesis in patients with a typical history and physical examination, arthrocentesis should be considered in any patient if there is any concern for SA.

Patients with moderate episodes may require colchicine (1 mg by mouth, then 0.5 mg every 2 hours until diarrhea develops, or until a total of 8 mg has been administered). Colchicine inhibits phagocytosis of crystals by neutrophils. Colchicine is generally safe; however, bone marrow suppression, renal injury, and hepatic injury may occur, particularly in patients with renal insufficiency and in those who are given colchicine intravenously (IV).1 Corticosteroids may be used to treat gout but probably should be selected for patients with no signs of infection on arthrocentesis.

Care should be taken to not change prophylactic gout medications without consultation with the patient’s primary doctor or rheumatologist, because such changes (increases or decreases) may precipitate a gouty episode. Prophylactic medications include colchicine, NSAIDs, and corticosteroids. Patients may also be taking allopurinol, a xanthine oxidase inhibitor, which decreases the production of urate from purines. Additionally, patients may require medications that increase renal clearance of urate (e.g., probenicid, sulfinpyrazone, salicylates).1

REFERENCES

1. Emmerson BT. The management of gout. N Engl J Med 1996;334:445-451.

2. Agudelo CA, Wise CM. Crystal-associated arthritis in the elderly. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 2000;26:527-546.

3. Rott KT, Agudelo CA. Gout. JAMA 2003;289:2857-2860.

23-6 Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

Robert Hendrickson

Clinical Presentation

Patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) may present to the emergency department (ED) with their first symptoms of SLE or with lupus flares in those with established disease. Symptoms may include skin rashes—a “classic” malar rash (erythema of the nose, cheeks, and forehead), vasculitic rashes (common at the nail bed), and discoid lesions (raised erythematous plaques)— arthritis, myositis/myalgias, tenosynovitis, and fever. SLE may also cause asymptomatic lupus nephritis (proteinuria, renal failure, nephrotic syndrome), serositis (myocarditis, pericarditis, pleuritis), myocardial infarction (MI, from coronary artery vasculitis), oral ulcers, anemia, and thromobocytopenia. Central nervous system manifestations include vasculitis, cerebrovascular accident (CVA), and cerebritis (alterations of mental status, focal neurologic deficits, psychosis, and seizures).1

Pathophysiology

SLE is molded by genetic, endogenous, and environmental factors. Defects in suppressor T cells lead to an overabundance of B cells and the production of antibodies, including anti-DNA and antinuclear antibodies (ANA), that produce disease directly or through immunecomplex formation.

Diagnosis

See Table 23-6. Antinuclear antibodies are 95% sensitive in detecting SLE, although false-positive results occur with hydralazine and procainamide use, hepatitis, subacute bacterial endocarditis (SBE), and primary biliary cirrhosis.2 Anti-double-stranded DNA (anti-ds DNA) and anti-Smith antibodies are specific for SLE.

TABLE 23-6 Classification Criteria for Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Clinical Complications

Complications include CVA, cerebritis, myocarditis/pericarditis, vasculitis, MI, renal failure, nephrotic syndrome, gastrointestinal vasculitis, hemolysis, and pulmonary fibrosis.

Management

Rheumatologic consultation or close follow-up with a qualified provider should be initiated for all patients with suspected SLE. Patients with minor inflammatory conditions, such as arthralgias or pericarditis, may be treated with nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (avoid in patients with nephritis) and with corticosteroids.1 Patients with severe chronic disease may also be treated with antimalarial agents (chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine) and immunosuppressive drugs (azathioprine, cyclophosphamide).2

Patients with minor conditions (e.g., monoarticular arthralgia) or minor flares of chronic SLE can often be discharged from the ED. Patients with severe conditions (e.g., renal failure, cerebritis) may require aggressive therapy, including intravenous (IV) steroids, immunosuppressive drugs, and admission to the hospital. Consultation with a rheumatologist, if possible, may be helpful in these cases.

REFERENCES

1. Mills JA. Systemic lupus erythematosus. N Engl J Med 1994;330:1871-1879.

2. Petri M. Treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus: an update. Am Fam Physician 1998;57:2753-2760.

23-7 Discoid Lupus

Bjorn Miller

Clinical Presentation

Patients may have red, scaly, round lesions (coin lesions) on sun-exposed skin such as the face, hands, and neck. As lesions progress, the scale may thicken and become adherent, with central depigmentation. Lesions often leave scarring or alopecia once they heal. The skin lesions are typically asymptomatic, are typically 5 to 20 mm in diameter, and can produce pain or pruritis.1,2 The lesions can last for months to years.3

Pathophysiology

Discoid lupus is a chronic, scarring, atrophy-producing skin disorder that produces few systemic manifestations. The disease is possibly separate from systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), or it may be considered a nonsystemic form of SLE.

The origin of the disease is not well-understood, but it is thought that genetically predisposed individuals have an abnormal autoimmune T-cell response to some viral, hormonal, or environmental stimuli. Scaly plaques typically show follicular plugging that tends to heal with atrophy, scarring, and hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation. Biopsy shows hyperkeratosis, follicular plugging, and atrophy of the epidermis.3

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree