CHAPTER 2 Respiratory system

Assessing The Airway

History and examination

Predictive tests

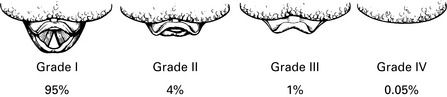

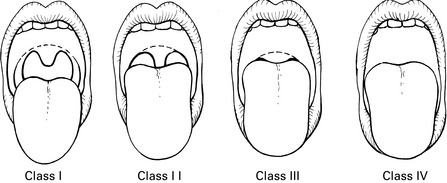

Mallampati classification (Mallampati et al 1985)

The patient sits upright with the head in the neutral position and the mouth open as wide as possible, with the tongue extended to maximum. The following structures are visible (Fig. 2.2):

Class I view is grade I intubation >99% of the time. Class IV view is grade III or IV intubation 100% of the time.

This classification may fail to predict >50% of difficult intubations.

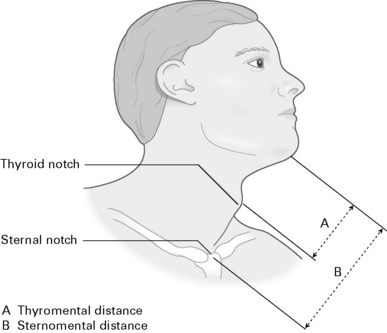

Thyromental distance (Patil et al 1983)

Measure from the upper edge of the thyroid cartilage to tip of the jaw with the head fully extended (Fig. 2.3). A short thyromental distance equates with an anterior larynx which is at a more acute angle and also results in less space for the tongue to be compressed into by the laryngoscope blade. This is a relatively unreliable test unless combined with other tests:

Sternomental distance (Savva 1994)

Measure from the sternum to the tip of the mandible with the head extended (Fig. 2.3). A sternomental distance of ≤12.5 cm predicts difficult intubation.

Horizontal length of mandible

Horizontal mandibular length >9 cm is suggestive of a good laryngoscopic view.

Wilson risk score (Wilson 1993; see Table 2.1)

| Parameter | Risk level |

|---|---|

| Weight | 0–2 (e.g. >90 kg = 1; >110 kg = 2) |

| Head and neck movement | 0–2 |

| Jaw movement | 0–2 |

| Receding mandible | 0–2 |

| Buck teeth | 0–2 |

| Maximum | 10 points |

Radiographic predictors of difficult intubation

These have the disadvantage of X-ray exposure and thus cannot be performed as routine tests.

Combined indicators

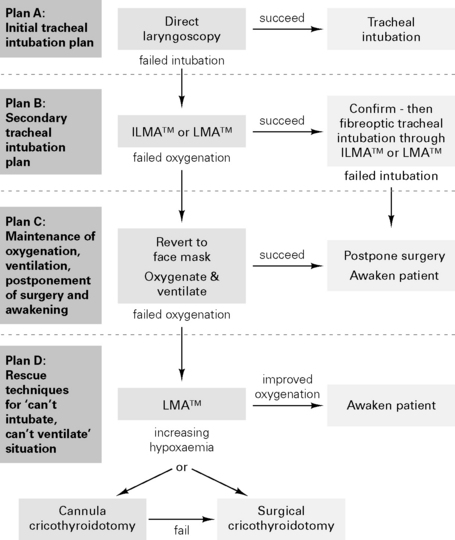

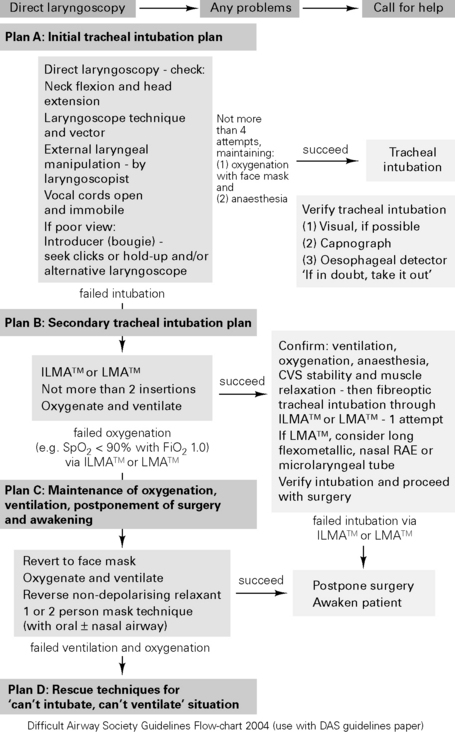

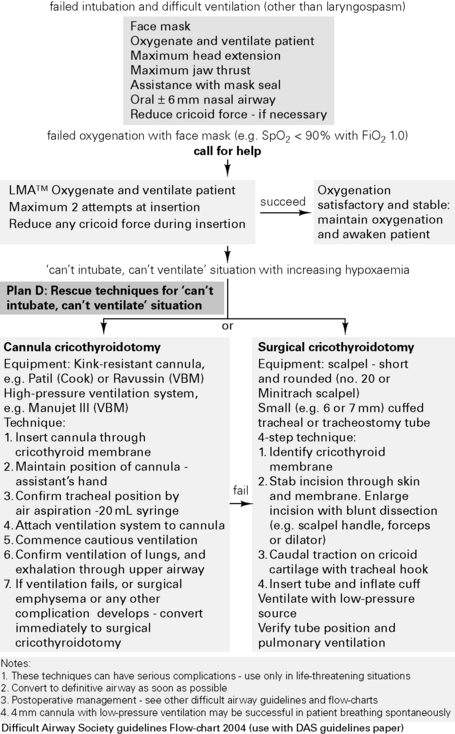

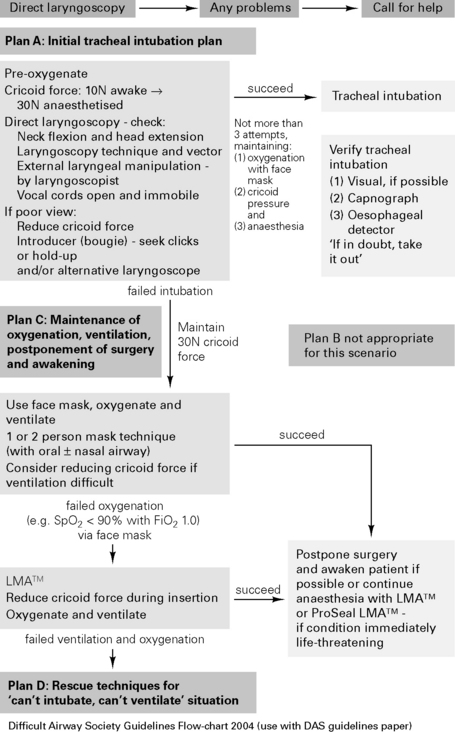

Difficult Airway Society Guidelines for Management of the Unanticipated Difficult Intubation 2004

Problems with tracheal intubation are the most frequent cause of anaesthetic death in the analyses of records of the UK medical defence societies. The Difficult Airway Society (DAS) has developed guidelines for management of the unanticipated difficult intubation in an adult non-obstetric patient, see http://www.das.uk.com/home

Arné J., Descoins P., Ingrand P., et al. Preoperative assessment for difficult intubation in general and ENT surgery: predictive value of a clinical multivariate risk index. Br J Anaesth. 1998;80:140-146.

Benumof J.L. Management of the difficult airway. Anesthesiology. 1991;75:1087-1110.

Cass N.M., James N.R., Lines V. Difficult laryngoscopy complicating intubation for anaesthesia. BMJ. 1956;1:488-489.

Charters P. What future is there for predicting difficult intubation? Br J Anaesth. 1996;77:309-311.

Chou H.C., Wu T.L. Mandibulohyoid distance in difficult laryngoscopy. Br J Anaesth. 1993;71:335-339.

Cormack R.S., Lehane. Difficult tracheal intubation in obstetrics. Anaesthesia. 1984;39:1105-1111. Difficult Airway Society, 2004, British Airway Society Guidelines Flow-chart 2004, http://www.das.uk.com/files/rsi-Jul04-A4.pdf.

Freck C.M. Predicting difficult intubation. Anaesthesia. 1991;46:1005-1008.

Henderson J.J., Popat M.T., Latto I.P., et al. Difficult Airway Society guidelines for management of the unanticipated difficult intubation. Anaesthesia. 2004;59:675-694.

Lavery G.G., McCloskey B.V. The difficult airway in adult critical care. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:2163a-2173a.

Lee A., Fan L.T.Y., Gin T., et al. A systematic review (meta-analysis) of the accuracy of the Mallampati tests to predict the difficult airway. Anesth Analg. 2006;102:1867-1878.

Mallampati S.R., Gatt S.P., Gugino L.D., et al. A clinical sign to predict difficult intubation: a prospective study. Can J Anaesth. 1985;32:429-434.

Nichol H.L., Zuck D. Difficult laryngoscopy – the ‘anterior’ larynx and the atlanto-occipital gap. Br J Anaesth. 1983;55:141-143.

Patil V.U., Stehling L.C., Zaunder H.L. Fibreoptic endoscopy in anaesthesia. Chicago: Year Book Medical Publishers, 1983.

Popat M. The airway. Anaesthesia. 2003;58:1166-1170.

Savva D. Prediction of difficult tracheal intubation. Br J Anaesth. 1994;73:149-153.

Vaughan R.S. Predicting difficult airways. BJA CEPD Reviews. 2001;1:44-47.

White A., Kander P.L. Anatomical factors in difficult direct laryngoscopy. Br J Anaesth. 1975;47:468-474.

Wilson M.E. Predicting difficult intubation. Br J Anaesth. 1993;71:333-334.

Anaesthesia And Respiratory Disease

Smoking

Effects of smoking

Preoperative cessation of smoking (Box 2.1)

A study in patients undergoing CABG (Warner 2006) showed that in those stopping smoking, the incidence of postoperative pulmonary complications did not fall until at least 8 weeks had elapsed:

Box 2.1 Effects of cessation of smoking

| 12–24 h | Clearance of carbon monoxide |

| 2–10 days | Decreased upper airway reactivity |

| 1–2 months | Increase in postoperative pulmonary complications (Bluman et al 1998) |

| 6 months | Decrease in postoperative pulmonary complications |

| Years | Reduced risk of COPD, ischaemic heart disease, lung cancer and cerebrovascular disease |

Chronic bronchitis

Chronic bronchitis is defined as productive cough >3 months of the year for ≥2 years.

Effects of general anaesthesia

ratios. Increased shunting (shunt fraction during GA: 11% during spontaneous breathing, 14% during IPPV)

ratios. Increased shunting (shunt fraction during GA: 11% during spontaneous breathing, 14% during IPPV)All these factors result in an increased A–aO2 (difference in alveolar and arterial oxygen tensions), which persists for at least 1–2 h postoperatively. Diaphragm may recover from neuromuscular blockade prior to muscles involved in coughing and swallowing. Postoperative wound pain, abdominal distension, pulmonary venous congestion and a supine posture all increase CC–FRC and result in further alveolar collapse.

Anaesthesia for chronic respiratory disease

Risk factors for postoperative pulmonary complications

American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification:

Anaesthetic techniques

Aims

Use either regional/local technique or maximal support approach with GA. Plan elective surgery for summer.

<50% = high risk (obstructive pattern)

<50% = high risk (obstructive pattern) <50% = high risk (restrictive pattern)

<50% = high risk (restrictive pattern)