CHAPTER 128

Radial Head Fracture

Presentation

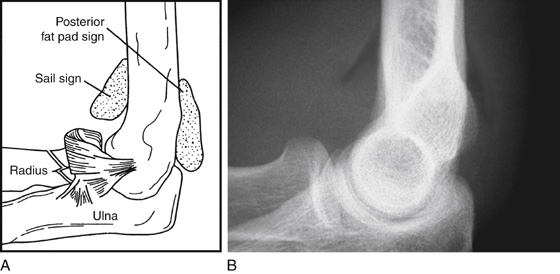

A patient has fallen on an outstretched hand and has a normal, nonpainful shoulder, wrist, and hand, but, on careful examination, he has pain in the elbow joint. Swelling may be noted over the antecubital fossa, and the patient may be able to fully flex the elbow joint, but there is pain and decreased range of motion on extension, supination, and pronation. Tenderness is greatest on palpation over the radial head. Radiographs may show a fracture of the head of the radius. Often, however, no fracture is visible, and the only radiographic signs are of an elbow effusion or hemarthrosis pushing the posterior fat pad out of the olecranon fossa and the anterior fat pad out of its normal position on the lateral view (Figure 128-1). In all radiographic views, a line down the center of the radius should point to the capitellum of the lateral condyle, ruling out a dislocation.

Figure 128-1 A and B, Radiologic evidence of elbow hemarthrosis. (Adapted from Raby N, Berman L, de Lacey G: Accident and emergency radiology. Philadelphia, 2005, Saunders.)

What To Do:

Obtain a detailed history of the mechanism of injury and a physical examination, looking for the features described, and, when present, obtain radiographs of the elbow, looking for visible fat pads as well as fracture lines. The evaluation should include an assessment of neurovascular status and a comparison with the uninjured elbow for baseline motion, strength, and stability. Examine the shoulder and wrist on the affected side to rule out an associated injury.

Obtain a detailed history of the mechanism of injury and a physical examination, looking for the features described, and, when present, obtain radiographs of the elbow, looking for visible fat pads as well as fracture lines. The evaluation should include an assessment of neurovascular status and a comparison with the uninjured elbow for baseline motion, strength, and stability. Examine the shoulder and wrist on the affected side to rule out an associated injury.

Radiographs are unnecessary if the patient can fully extend the elbow with the forearm in supination. It can be assumed that there is no elbow fracture, and no further treatment is necessary other than reassurance and the possible use of acetaminophen or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

Radiographs are unnecessary if the patient can fully extend the elbow with the forearm in supination. It can be assumed that there is no elbow fracture, and no further treatment is necessary other than reassurance and the possible use of acetaminophen or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

For nondisplaced fractures, a sling is all that is necessary. Refer these patients to an orthopedist within 3 to 5 days for definitive care. The patient should be instructed to not wait longer, because early mobilization is thought to be important for proper healing.

For nondisplaced fractures, a sling is all that is necessary. Refer these patients to an orthopedist within 3 to 5 days for definitive care. The patient should be instructed to not wait longer, because early mobilization is thought to be important for proper healing.

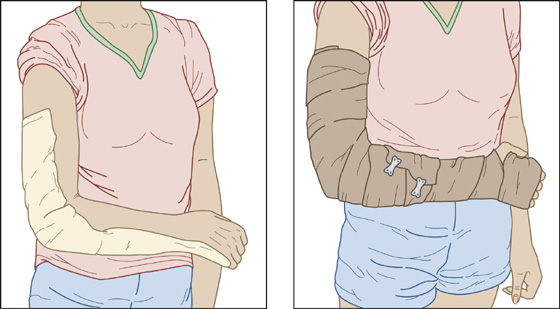

If there is a displaced or comminuted radial head fracture, immobilize the elbow in 90% of flexion and the forearm in full supination (preventing pronation and supination of the hand) with a gutter splint extending from proximal humerus to hand, and then place in a sling for comfort (Figure 128-2). These patients should also receive early orthopedic consultation or follow-up, because with displacement of greater than 2 mm or comminution, surgical repair may be recommended.

If there is a displaced or comminuted radial head fracture, immobilize the elbow in 90% of flexion and the forearm in full supination (preventing pronation and supination of the hand) with a gutter splint extending from proximal humerus to hand, and then place in a sling for comfort (Figure 128-2). These patients should also receive early orthopedic consultation or follow-up, because with displacement of greater than 2 mm or comminution, surgical repair may be recommended.

Figure 128-2 Long-arm gutter splint for complex radial head fractures.

Provide adequate analgesia, especially during the first few days. NSAIDs alone or acetaminophen with hydrocodone (Vicodin) may be appropriate.

Provide adequate analgesia, especially during the first few days. NSAIDs alone or acetaminophen with hydrocodone (Vicodin) may be appropriate.

When there is an inability to fully extend the elbow, along with a positive fat pad sign without a visible fracture, explain to the patient the probability of a fracture, despite radiographs that only demonstrate an effusion. Treat it as a nondisplaced fracture (see earlier) and arrange for follow-up.

When there is an inability to fully extend the elbow, along with a positive fat pad sign without a visible fracture, explain to the patient the probability of a fracture, despite radiographs that only demonstrate an effusion. Treat it as a nondisplaced fracture (see earlier) and arrange for follow-up.

For uncomplicated fractures, range-of-motion exercises should begin within 3 to 7 days to reduce the risk for developing permanent loss of motion because of elbow joint contractures.

For uncomplicated fractures, range-of-motion exercises should begin within 3 to 7 days to reduce the risk for developing permanent loss of motion because of elbow joint contractures.

What Not To Do:

Do not obtain radiographs on all patients with minimal symptoms after a minor injury. The elbow extension test, as described earlier, can be used as a sensitive screening test for patients with acute injury to the elbow. Patients who can fully extend the affected elbow can be safely treated without radiography.

Do not obtain radiographs on all patients with minimal symptoms after a minor injury. The elbow extension test, as described earlier, can be used as a sensitive screening test for patients with acute injury to the elbow. Patients who can fully extend the affected elbow can be safely treated without radiography.

Do not miss a dislocation of the radial head. Examine all radiographs; a line drawn through the radial head and shaft should always line up with the capitellum.

Do not miss a dislocation of the radial head. Examine all radiographs; a line drawn through the radial head and shaft should always line up with the capitellum.

Do not treat simple radial head fractures (minimal or no displacement without comminuted fragments) with prolonged immobilization. Joint motion is difficult to recover even with extensive physical therapy. Avoiding the problem by providing early mobilization is preferable to attempting to reverse an established joint contracture.

Do not treat simple radial head fractures (minimal or no displacement without comminuted fragments) with prolonged immobilization. Joint motion is difficult to recover even with extensive physical therapy. Avoiding the problem by providing early mobilization is preferable to attempting to reverse an established joint contracture.

Discussion

The elbow is a hinge (ginglymus) joint between the distal humerus, the proximal ends of the radius and ulna, and the superior radioulnar joint. The lateral capitellum of the distal humerus articulates with the radial head, enabling flexion and extension as well as pronation and supination.

Radial head fractures are the result of trauma, usually from a fall on the outstretched arm. The force of impact is transmitted up the hand through the wrist and forearm to the radial head, which is forced into the capitellum, where it is fractured or deformed.

Small nondisplaced fractures of the radial head may show up on radiographs weeks later or never. Because pronation and supination of the hand are achieved by rotating the radial head on the capitellum of the humerus, very small imperfections in the healing of a radial head fracture that involves the joint may produce enormous impairment of hand function, which may be only partly improved by surgical excision of the radial head. Early orthopedic referral is essential, because treatment is controversial.

Management of complex radial head fractures depends on the severity of the fracture and associated injuries and includes early motion, open reduction and internal fixation with screws and wires, immediate and delayed excision, and the use of a prosthesis.

Most occult or small radial head fractures are treated symptomatically with early range-of-motion exercises and generally heal without functional loss.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree