CHAPTER 151

Puncture Wounds

Presentation

Most commonly, the patient will have stepped or jumped onto a nail. There may be pain and swelling, but often the patient is only asking for a tetanus shot. He can usually be found in the emergency department with his foot soaking in a basin of povidone-iodine (Betadine) solution. The wound entrance usually appears as a linear or stellate tear in the cornified epithelium on the plantar surface of the foot.

What To Do:

Obtain a detailed history to ascertain the time interval since injury, the force involved in creating the puncture (if possible), the estimated depth of penetration, and the relative cleanliness of the penetrating object. Also ascertain whether there was believed to be complete or partial removal of the object and if there is any residual foreign body sensation in the wound. Note the type of footwear (tennis or rubber-soled shoes) and the potential for foreign body retention. Also ask about tetanus immunization status and underlying health problems that may potentially diminish host defenses. (In multiple studies, diabetes has been associated with an increased incidence of infectious complications from plantar puncture wounds.)

Obtain a detailed history to ascertain the time interval since injury, the force involved in creating the puncture (if possible), the estimated depth of penetration, and the relative cleanliness of the penetrating object. Also ascertain whether there was believed to be complete or partial removal of the object and if there is any residual foreign body sensation in the wound. Note the type of footwear (tennis or rubber-soled shoes) and the potential for foreign body retention. Also ask about tetanus immunization status and underlying health problems that may potentially diminish host defenses. (In multiple studies, diabetes has been associated with an increased incidence of infectious complications from plantar puncture wounds.)

Have the patient lie prone, backward on the gurney, so that raising the head of the bed flexes his knee and brings the sole of the foot into clear view. Place the foot on a pillow. Clean the surrounding skin, and carefully inspect the wound. Provide good lighting, and take your time. Examine the foot for signs of deep injury, such as swelling and pain with passive motion of the toes. Although the occurrence is unlikely, test for loss of sensory or motor function.

Have the patient lie prone, backward on the gurney, so that raising the head of the bed flexes his knee and brings the sole of the foot into clear view. Place the foot on a pillow. Clean the surrounding skin, and carefully inspect the wound. Provide good lighting, and take your time. Examine the foot for signs of deep injury, such as swelling and pain with passive motion of the toes. Although the occurrence is unlikely, test for loss of sensory or motor function.

If the puncture was created by a slender object, such as a sewing needle or thumb tack that is verified to have been removed intact, no further treatment is necessary. If there is any question that a piece may have broken off in the tissue, obtain radiographs (see Chapter 148).

If the puncture was created by a slender object, such as a sewing needle or thumb tack that is verified to have been removed intact, no further treatment is necessary. If there is any question that a piece may have broken off in the tissue, obtain radiographs (see Chapter 148).

Most metal and glass foreign bodies are visualized on plain films, whereas plastic, aluminum, rubber fragments, thorns, spines, and wood are more radiolucent and may require ultrasonography, a CT scan, or MRI for visualization. Retained foreign bodies increase the potential for infection and should be suspected in patients who present with infection, who are not responding to treatment for infection, who have inordinate pain, who believe that there is a foreign body in their wound, or who have a foreign body sensation when the puncture wound is palpated. These foreign bodies must be removed (see Chapter 154).

Most metal and glass foreign bodies are visualized on plain films, whereas plastic, aluminum, rubber fragments, thorns, spines, and wood are more radiolucent and may require ultrasonography, a CT scan, or MRI for visualization. Retained foreign bodies increase the potential for infection and should be suspected in patients who present with infection, who are not responding to treatment for infection, who have inordinate pain, who believe that there is a foreign body in their wound, or who have a foreign body sensation when the puncture wound is palpated. These foreign bodies must be removed (see Chapter 154).

With deep, highly contaminated wounds, orthopedic or podiatric consultation should be sought. With the most serious of these wounds, consideration should be given to providing a wide débridement in the operating room. This is done to prevent the catastrophic complication of osteomyelitis. Although controversial, deep wounds such as these may be considered for treatment with a prophylactic antibiotic.

With deep, highly contaminated wounds, orthopedic or podiatric consultation should be sought. With the most serious of these wounds, consideration should be given to providing a wide débridement in the operating room. This is done to prevent the catastrophic complication of osteomyelitis. Although controversial, deep wounds such as these may be considered for treatment with a prophylactic antibiotic.

If there was a deep puncture through a rubber-soled sport shoe, it may be reasonable (although not proven) to use a quinolone, such as levofloxacin (Levaquin), for 3 to 4 days, or, in children, cefuroxime axetil (Ceftin, Zinacef) to cover for Pseudomonas.

If there was a deep puncture through a rubber-soled sport shoe, it may be reasonable (although not proven) to use a quinolone, such as levofloxacin (Levaquin), for 3 to 4 days, or, in children, cefuroxime axetil (Ceftin, Zinacef) to cover for Pseudomonas.

Most superficial puncture wounds require only simple débridement, possibly with irrigation. In these wounds, prophylactic antibiotics are not indicated.

Most superficial puncture wounds require only simple débridement, possibly with irrigation. In these wounds, prophylactic antibiotics are not indicated.

The plantar surface of the foot is exceedingly well innervated, and even simple débridement is likely to be painful. In appropriate circumstances and depending on the location of the injury/foreign body, consider performing a posterior tibial or a sural nerve block.

The plantar surface of the foot is exceedingly well innervated, and even simple débridement is likely to be painful. In appropriate circumstances and depending on the location of the injury/foreign body, consider performing a posterior tibial or a sural nerve block.

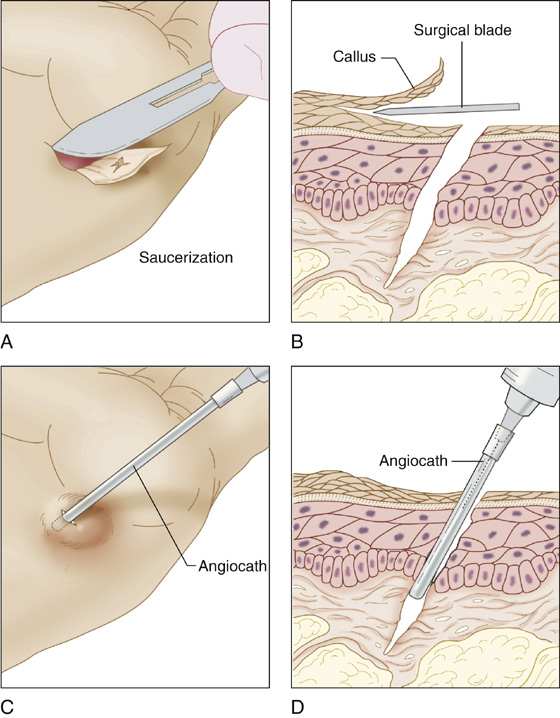

Saucerize (shave) the puncture wound using a No. 10 scalpel blade to remove the surrounding cornified epithelium and any debris that has collected beneath its surface (Figure 151-1, A and B). Alternatively, the jagged cornified epidermal skin edges overlying the puncture tract may be painlessly trimmed using a scalpel or scissors.

Saucerize (shave) the puncture wound using a No. 10 scalpel blade to remove the surrounding cornified epithelium and any debris that has collected beneath its surface (Figure 151-1, A and B). Alternatively, the jagged cornified epidermal skin edges overlying the puncture tract may be painlessly trimmed using a scalpel or scissors.

Figure 151-1 Simple débridement and irrigation for puncture wounds.

If debris is found, remove what is visible and then gently slide a large-gauge blunt needle or an over-the-needle (Angiocath) catheter down the wound track and slowly irrigate with a physiologic saline solution, moving the catheter in and out until debris no longer flows from the wound (Figure 151-1, C and D). If the puncture wound is small and there is little room for effluent to exit, make a stab wound with a No. 15 blade through the dermis to enlarge the opening and allow the effluent to more easily escape.

If debris is found, remove what is visible and then gently slide a large-gauge blunt needle or an over-the-needle (Angiocath) catheter down the wound track and slowly irrigate with a physiologic saline solution, moving the catheter in and out until debris no longer flows from the wound (Figure 151-1, C and D). If the puncture wound is small and there is little room for effluent to exit, make a stab wound with a No. 15 blade through the dermis to enlarge the opening and allow the effluent to more easily escape.

Provide tetanus prophylaxis (see Appendix H).

Provide tetanus prophylaxis (see Appendix H).

Cover the wound with a Band-Aid and instruct the patient regarding the warning signs of infection.

Cover the wound with a Band-Aid and instruct the patient regarding the warning signs of infection.

Arrange for follow-up at 48 hours. Spend some time on documentation and patient education. Talk about delayed osteomyelitis and the importance of medical attention if there is continued aching or discomfort 1 to 2 weeks postinjury. Explain that even with proper care, foreign material may be embedded deeply in the wound, and infection could occur. Explain that in most cases, prophylactic antibiotics do not prevent these infections and that the best practice is close observation and aggressive therapy if infection occurs.

Arrange for follow-up at 48 hours. Spend some time on documentation and patient education. Talk about delayed osteomyelitis and the importance of medical attention if there is continued aching or discomfort 1 to 2 weeks postinjury. Explain that even with proper care, foreign material may be embedded deeply in the wound, and infection could occur. Explain that in most cases, prophylactic antibiotics do not prevent these infections and that the best practice is close observation and aggressive therapy if infection occurs.

Patients presenting 24 hours postinjury will often have an established wound infection. In addition to the débridement procedures described, patients who have an early infection usually respond quickly to an oral antistaphylococcal antibiotic, such as clindamycin (Cleocin), if they do not have a retained foreign body. Always suspect retained foreign bodies, and strongly consider imaging studies for all infected wounds that do not respond to antibiotics.

Patients presenting 24 hours postinjury will often have an established wound infection. In addition to the débridement procedures described, patients who have an early infection usually respond quickly to an oral antistaphylococcal antibiotic, such as clindamycin (Cleocin), if they do not have a retained foreign body. Always suspect retained foreign bodies, and strongly consider imaging studies for all infected wounds that do not respond to antibiotics.

Provide patients with crutches for non–weight bearing, and encourage them to soak the infected foot.

Provide patients with crutches for non–weight bearing, and encourage them to soak the infected foot.

Consider hospitalization for patients with severe infection or who have risk factors for serious complications (e.g., diabetes, peripheral vascular disease, immune suppression).

Consider hospitalization for patients with severe infection or who have risk factors for serious complications (e.g., diabetes, peripheral vascular disease, immune suppression).

What Not To Do:

Do not be falsely reassured by having the patient soak in Betadine. This does not provide any significant protection from infection and is not a substitute for débridement and irrigation.

Do not be falsely reassured by having the patient soak in Betadine. This does not provide any significant protection from infection and is not a substitute for débridement and irrigation.

Do not attempt a jet lavage within a puncture wound. This will only lead to subcutaneous infiltration of irrigant and the possible spread of foreign material and bacteria.

Do not attempt a jet lavage within a puncture wound. This will only lead to subcutaneous infiltration of irrigant and the possible spread of foreign material and bacteria.

Do not perform blind probing of a deep puncture wound. This is not likely to be of any value and may do harm.

Do not perform blind probing of a deep puncture wound. This is not likely to be of any value and may do harm.

Do not obtain radiographs for simple nail punctures, except for the unusual case in which large radiopaque particulate debris is suspected to be deeply embedded within the wound or the physical examination suggests bony injury.

Do not obtain radiographs for simple nail punctures, except for the unusual case in which large radiopaque particulate debris is suspected to be deeply embedded within the wound or the physical examination suggests bony injury.

Do not routinely prescribe prophylactic antibiotics. Reserve them for patients with diabetes, peripheral vascular disease, immune suppression, or deep, highly contaminated wounds. In fact, there is insufficient evidence to recommend the use of prophylactic antimicrobials to decrease the incidence of serious infections in any of these puncture wounds.

Do not routinely prescribe prophylactic antibiotics. Reserve them for patients with diabetes, peripheral vascular disease, immune suppression, or deep, highly contaminated wounds. In fact, there is insufficient evidence to recommend the use of prophylactic antimicrobials to decrease the incidence of serious infections in any of these puncture wounds.

Do not ignore the patient who returns with a recurrent infection. If antibiotics fail to cure an initial wound infection, suspect a retained foreign body; obtain an ultrasonogram, CT scan, or MRI; and consult an appropriate foot surgeon.

Do not ignore the patient who returns with a recurrent infection. If antibiotics fail to cure an initial wound infection, suspect a retained foreign body; obtain an ultrasonogram, CT scan, or MRI; and consult an appropriate foot surgeon.

Do not ignore the patient who returns with delayed foot pain, even if there are minimal physical findings and radiographs are negative. Osteomyelitis may present weeks or even months after the initial injury. These patients demand special imaging to rule out a retained foreign body, and an erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) should be obtained. These patients should then be referred to a surgical foot specialist for a bone scan or MRI and, if there is evidence of bone infection, surgical débridement.

Do not ignore the patient who returns with delayed foot pain, even if there are minimal physical findings and radiographs are negative. Osteomyelitis may present weeks or even months after the initial injury. These patients demand special imaging to rule out a retained foreign body, and an erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) should be obtained. These patients should then be referred to a surgical foot specialist for a bone scan or MRI and, if there is evidence of bone infection, surgical débridement.

Do not begin soaks at home, unless there are early signs of developing infection.

Do not begin soaks at home, unless there are early signs of developing infection.

Discussion

The most common sites for puncture wounds are the feet. The complication rate from plantar puncture wounds is higher than the rate for puncture wounds elsewhere in the body (with the exception of the hands). One reason is the small distance from the plantar skin surface to bones and joints of the feet. Another is the force with which puncture wounds are inflicted when the weight of the body pushes against a sharp object. Additionally, penetration of a shoe and stocking by a nail (or other sharp object) can push foreign bodies into the deepest recesses of the wound. These foreign bodies are rarely seen on plain radiographs.

Small, clean, superficial puncture wounds uniformly do well. The pathophysiology and management of a puncture wound, therefore, depend on the material that punctured the foot, the location of the wound, the depth of penetration, the time to presentation, the footwear penetrated, whether there is an indoor versus a more infection-prone outdoor injury, and the underlying health status of the victim. Punctures in the metatarsophalangeal joint area may also be of higher risk for serious wound complications because of the greater likelihood of penetration of joint, tendon, or bone. Early presenters tend to be children or adults seeking tetanus prophylaxis. These patients tend to have a low incidence of infection. Patients who present late usually have increasing pain, swelling, or drainage as evidence of an early or established infection. Unsuspected retained foreign bodies, often pieces of a tennis shoe or sock, are a source of serious infection. Other common foreign bodies include rust, gravel, grass, straw, and dirt.

When the foot is punctured, the cornified epithelium acts as a spatula, cleaning off any loose material from the penetrating object as it slides by. This debris often collects just beneath this cornified layer, which then acts like a trap door, holding it in. Left in place, this debris may lead to early abscess formation, cellulitis, and lymphangitis. Saucerization allows the removal of debris and the unroofing of superficial small foreign bodies or abscesses found beneath the thickly cornified skin surfaces.

There are many different ways to manage plantar puncture wounds. There are very few scientific data to support any one universal standard of care. Some physicians are very conservative in their approach, whereas others advocate liberal use of radiographs, prophylactic antibiotics, and aggressive débridement procedures that include removing a core of tissue the length of the puncture wound. Some believe that irrigation of deep puncture wounds is futile because the irrigant solution does not completely drain out of the wound. The approach presented here is reasonable and rational, given the data that are available at this time. Because there is no clear evidence supporting either a conservative or an aggressive approach, it is wise to get your patient involved in the decision-making process, and to ensure close follow-up, regardless of the approach.

Puncture wounds of the foot reportedly have an overall infection rate as high as 15%. The probability of wound infection is increased with deeper penetrating injuries, delayed presentation (>24 hours), gross contamination, penetration through a rubber-soled shoe, outdoor injuries, injuries that occur from the neck of the metatarsals to the web space of the toes, and decreased resistance to infection. Specifically, diabetic patients typically present for care later and have higher rates of osteomyelitis (up to 35%). In one study, they were also 5 times more likely to require multiple operations and 46 times more likely to have a lower extremity amputation as a result of a plantar puncture wound.

Joint puncture wounds have the potential to penetrate the joint capsule and produce septic arthritis. Penetration of bone and periosteum can produce osteomyelitis.

Osteomyelitis caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa remains the most devastating of puncture wound complications. The exact incidence of osteomyelitis remains uncertain and is estimated to be between 0.04% and 0.5% in plantar puncture wounds. The metatarsal heads are most at risk for osteomyelitis. A nail through the sole of a tennis or sport shoe is known to inoculate Pseudomonas organisms. Any patient who is considered to have penetration of the bone, joint space, or plantar fascia, particularly over the metatarsal heads, should be warned of the potential for serious infection and then referred to an orthopedic surgeon or podiatrist for early follow-up evaluation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree