Psychosocial

27-1 Munchausen’s Syndrome

Michael Greenberg

Clinical Presentation

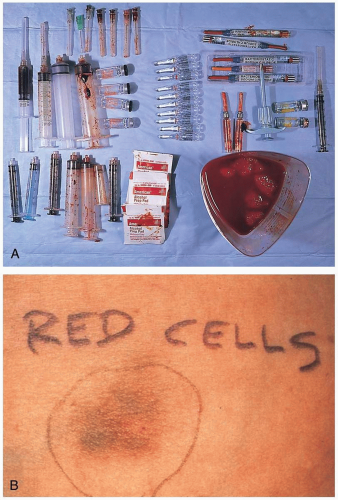

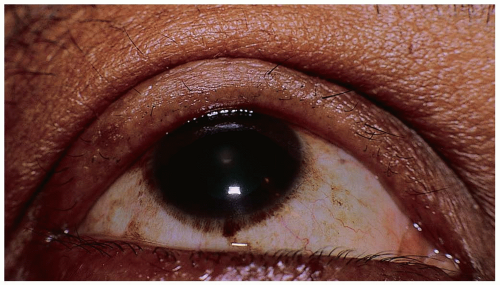

Patients with Munchausen’s syndrome (MS), who usually are men, can present with any of a myriad of symptoms and complaints referable to one or more body systems.1 However, all signs and symptoms in these patients are factitious and fabricated.1,2,3 Patients may present with complaints of chest pain, shortness of breath, or seizures, or with problems related to self-induced fevers, infections, or bleeding. Feigned memory loss, suicidal thoughts, or hallucinations may be manifest. Patients typically present to many hospitals in different locations, using different names and aliases.

Pathophysiology

MS is a form of so-called factitious disorder and is characterized by feigned or simulated illness, “pseudologia fantastica” (persistent and pathologic lying), and “peregrinations,” or moving frequently from place to place (or hospital to hospital).1 Individuals with MS appear to be distinctly different from malingerers, whose goal is to attain some tangible benefit (e.g., occupational- or insurance-derived compensation) from feigned disease. The only apparent goal of an individual with MS is to become a patient and receive unnecessary medical treatment. Most MS patients are men with work experience in health care settings. They are often noted to be “socially conforming” as well as “pleasant and compliant in their relationships with hospital staff”.1

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of MS is very difficult, especially in the setting of the emergency department. The key to correct diagnosis is to maintain an increased index of suspicion. Valuable clues to this syndrome may be obtained by contacting previous caregivers and institutions who provided care to the patient in the past. MS patients usually allow a wide variety of invasive and even operative procedures to be performed.

Clinical Complications

Complications include unnecessary medication use, unnecessary hospitalizations with the potential for iatrogenic illness, and unnecessary surgical procedures, as well as malpractice lawsuits that may derive from any of these.

Management

Patients with MS are often deemed to be untreatable and virtually impossible to manage. Although the prognosis for these patients is generally poor, attempts should be made to have psychiatric evaluation undertaken at the earliest possible moment.

REFERENCES

1. Turner J, Reid S. Munchausen’s syndrome. Lancet 2002;359:346-349.

2. Mehta NJ, Khan IA. Cardiac Munchausen’s syndrome. Chest 2002;122:1649-1653.

3. Chew BH, Pace KT, Honey RJ. Munchausen syndrome presenting as gross hematuria in two women. Urology 2002;59:601.

27-2 Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia Nervosa

Judith Eisenberg

Clinical Presentation

Although anorexic patients are more likely to appear cachectic, both anorexic and bulimic patients may present with sequelae of malnutrition.

Pathophysiology

These disorders are characterized by substantial eating disturbances that arise from a distorted body image.1 Eating disorders are thought to be multifactorial, with neurochemical, genetic, cultural, and psychodevelopmental components. Although there is female gender predominance, there is no difference in incidence related to socioeconomic class or ethnic background. It is estimated that 3% of all young women in the United States suffer from a form of eating disorder.1,2

Diagnosis

The diagnostic criteria for anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa were set out in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition (DSM-IV).1,2

Criteria for Diagnosis of Anorexia Nervosa

Body weight less than 85% of expected weight, or body mass index less than 17.5

Intense fear of weight gain

Inaccurate perception of own body weight, size, or shape

Amenorrhea in girls after menarche

Criteria for Diagnosis of Bulimia Nervosa

Recurrent binge eating at least twice a week for 6 months

Recurrent purging, excessive exercise, or fasting at least twice a week for 3 months

Excessive concern about body weight or shape

Absence of anorexia nervosa

Clinical Complications

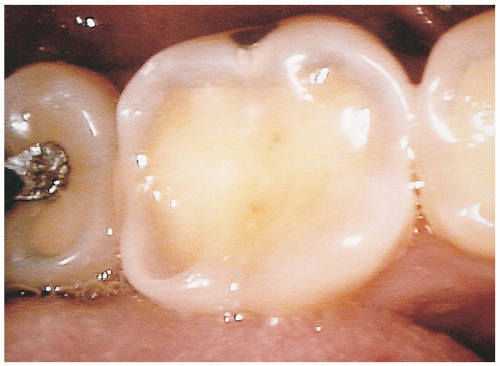

Potential complications include cardiac dysrhythmias, electrolyte abnormalities, decreased gastrointestinal motility with increased risk of perforation, hypotension, depression, and increased risk for suicide. Inadequate caloric intake may be severe enough to result in hair loss, amenorrhea, and growth arrest. Electrolyte and fluid losses may be exacerbated by laxative abuse. Bulimic patients may have dental caries, loss of dentin, and dorsal hand abrasions from forced emesis. These patients are also at increased risk for Mallory-Weiss tears from repetitive purging.1,2

Management

Treatment involves a multidisciplinary approach, with medical therapy aimed at correcting the sequelae of nutritional derangements from severe weight loss, and psychiatric treatment to correct the skewed body image and resultant depression. Psychopharmacology has not been very useful in anorexic patients, but selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) have some reported benefit in bulimic patients.2

REFERENCES

1. Vitousek K, Manke F. Personality variables and disorders in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. J Abnorm Psychol 1994;103:137-147.

2. Becker AE, Grinspoon SK, Klibanski A, Herzog DB. Current concepts: eating disorders. N Engl J Med 1999;340:1092-1098.

27-3 Trichotillomania

Michael Greenberg

Clinical Presentation

Patients with trichotillomania present with patchy alopecia.

Pathophysiology

Trichotillomania is a disorder involving the compulsive and repetitive pulling and extraction of body hair.1,2 The cause for trichotillomania is not known; however, some have characterized this psychiatric disorder as a form of castration surrogate, because hair often is portrayed as a symbol of sexuality and virility.

Diagnosis

Trichotillomania is diagnosed based on clinical findings. However, many patients hide the disorder under wigs, hats, or other coverings and avoid situations in which the disorder would become obvious (e.g., water sports). Scalp biopsy may be necessary in some cases if the cause is unclear. Trichotillomania may involve other than head hair; trichotillomaniacs may also pull eyebrows, pubic hair, chest hair, and axillary hair.1,2

Clinical Complications

Complications include various psychiatric comorbidities as well as obvious cosmetic issues.

Management

Maximally effective treatment involves the coadministration of pharmacotherapy with behavioral modification therapy. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are the most popular medications used for this disorder, but virtually every known psychotropic medication has been tried in the treatment of trichotillomania.1,2

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree