4 Psychophysiology and pelvic pain

Psychophysiology in historical perspective

Although scientific advances have helped to clarify some mind–body issues, they are far from being resolved. How can the subjective qualities and the essence of a state of consciousness be explained in naturalistic terms? The most recognized modern form of dualism comes from the writings of René Descartes (1641) (see Marenbon 2007), and holds that the mind is a separate mental substance. Descartes clearly identified the mind with consciousness and self-awareness, and distinguished it from the brain, which he identified with intelligence. He was the first to formulate the mind–body problem in the form that it exists today.

Modern psychophysiological research

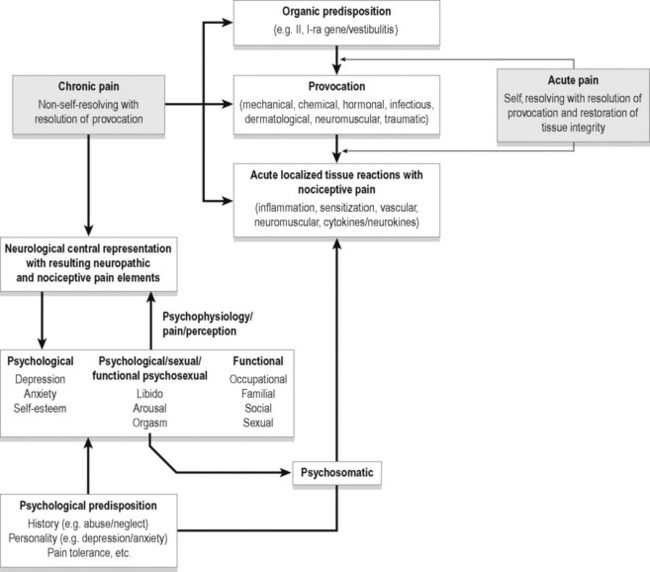

A wide variety of provocative events can lead to localized acute tissue reactions with resulting nociceptive pain. This acute pain most often resolves on resolution of the provocative factors. In the presence of organic and psychological predisposition this pain may become chronic pain with the addition of neuropathic elements to the nociceptive factors. With urogenital pain, psychological, sexual and functional states are adversely affected adding a psychophysiological element to the chronic pain. Figure 4.1 depicts some potential relationships among biological and psychological factors in chronic pelvic pain.

Prostate and pelvic pain

One recent study (Ullrich et al. 2007) of benign prostate hyperplasia (BPH) implicated the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and sympathetic nervous system reactivity in prostate enlargement. Eighty-three men with BPH underwent an experimental stress task (public speaking, videotaped). The degree of stress was defined physiologically as rises in cortisol and blood pressure. Personal appraisal of the situation was not assessed. Subjects showing stronger stress responses were found to have larger prostate volume and more objective and subjective indications of urinary tract dysfunction. Among the hypotheses for this relationship were decreased apoptosis (slowed prostatic cell death) as a result of chronically greater sympathetic input; increased pelvic floor muscle tension; greater prostate contractility (stimulated by exogenous epinephrine and norepinephrine); and stress-induced hyperinsulinaemia promoting prostate growth. Not all BPH cases involve pain, but when pain is present it can stimulate the sympathetic system, create a feedback loop, and add to the problem.

Anderson et al. (2005, 2008, 2009) compared men with chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CPPS) with asymptomatic controls for evidence of differences in stress levels. Various psychological tests revealed more perceived stress and anxiety in the CPPS patients, plus more somatization, hostility, interpersonal sensitivity and paranoid ideation. Salivary cortisol on awakening was also measured and found to be significantly higher in the pain patients. This rise in cortisol is thought to indicate the hippocampus preparing the HPA axis for anticipated stress. Cortisol has been found to be higher in situations such as waking on the day of a dance competition (Rohleder et al. 2007), in high-school teachers reporting higher job strain (Steptoe et al. 2000), and waking on work days compared with weekends (Schlotz et al. 2004).

Anderson and Wise have advanced an explanation of chronic, otherwise unexplained pelvic pain as frequently stemming from myofascial trigger points (Wise & Anderson 2008) (see Chapter 16). In their view, much long-term pelvic pain develops from the shortening and tensing of pelvic muscles, eventually creating and then aggravating trigger points, and this condition can be treated with manual release techniques. The more complete treatment, however, involves cultivating a skill for dropping into deep relaxation along with changing attention (‘paradoxical relaxation’) in a way that contradicts the usual tensing and bracing against pain. This is achieved (in their programme) by progressively more muscular and emotional self-calming.

Trigger points were shown to be exacerbated by stressful emotion (Hubbard & Berkoff 1993, McNulty et al. 1994). EMG was recorded from an upper trapezius trigger point along with a signal from an adjacent area of the muscle without a trigger point. As emotional stress increased, the trigger point EMG increased its voltage even though the rest of the muscle did not. Also, described in Chen et al. (1998) was a demonstration of how electrical activity associated with trigger points in rabbits was abolished by phentolamine, a sympathetic antagonist. This supports the role of the autonomic nervous system in maintaining trigger points, and also is congruent with the cited research on the aggravating effect of negative emotion (anxiety) on trigger points (Simons 2004). Wise and Anderson’s protocol for pelvic pain treatment includes both thorough relaxation training and manual release of trigger points. One is temporarily curative, the other preventive.

Alexithymia and pelvic pain

The word ‘alexithymia’ refers to a relative inability to name feelings, or to verbally elaborate on feeling states. Its Greek roots belie its recent creation, less than 40 years ago, by psychiatrist Peter Sifneos (1973). The phenomenon and the concept existed long before its final naming. Physicians and psychotherapists had noted for many years the tendency of some patients to use very few words to describe their feelings; complex emotional states were reduced to simple terms such as ‘feeling bad’ or ‘upset’ without elaboration. This difficulty with feelings includes reflecting on them, naming them, discussing them and expressing them.

Researchers have pursued correlations between high scores on alexithymia scales such as the Toronto Alexithymia Scale (Bagby et al. 2006) and other problems such as dissociation, Asperger’s, autism, substance abuse, anorexia nervosa, somatic amplification and somatoform disorders. A functional disconnection between the two cerebral hemispheres or a right hemisphere deficit has been suggested, with incomplete evidence (Tabibnia & Zaidel 2005).

Most research on chronic pain and alexithymia has found a correlation between them. Celikel and Saatcioglu (2006) found that female chronic pain patients scored more than twice as high on alexithymia scales as controls, and there was also a positive correlation between alexithymia scores and duration of pain. Since the study design was not intended to distinguish direction of causation, it is conceivable that prolonged pain damages the right hemisphere, interfering with full experiencing and transfer of emotional material.

Porcelli et al. (1999) found a strong association between alexithymia and functional gastrointestinal disorders (66% had high alexithymia scores, whereas the population average is below 10%), and later (Porcelli et al. 2003) demonstrated that higher alexithymia scores predicted worse treatment outcome. Although anxiety and depression also predicted worse treatment outcome, the alexithymia scores were stable and independent of anxiety and depression, suggesting a unique contribution to failure to improve.

Hosoi et al. (2010) studied 129 patients with chronic pain from muscular dystrophy. Degree of alexithymia was significantly associated with higher pain intensity and more pain interference. Finally, Lumley et al. (1997) compared chronic pain patients to patients seeking treatment for obesity and nicotine dependence, to control for the variable of ‘treatment-seeking’. As predicted, the chronic pain patients scored higher on the alexithymia measures than either of the other groups. They also had higher levels of psychopathology, which can by itself confound and weaken treatment programmes for chronic pain.

Processing of emotional experience often involves revisiting traumatic or otherwise disturbing memories, which can be done alone or with the help of a friend, relative or therapist. Psychologist James Pennebaker has led the way in a body of research that repeatedly confirms the value of simply writing about undisclosed experiences and the deep feelings that have been kept private (Berry & Pennebaker 1993; Pennebaker 1997). This process of transforming inchoate memories and feelings into a linear, word-based account of an experience seems to be a key step in ‘adjusting’ to something unpleasant. Part of the value of psychotherapy lies in providing a safe forum for verbalizing one’s feelings about something for the first time, and this activity has therapeutic value regardless of response from another person.

This self-adjusting activity, however, is precisely what the individuals describable as ‘alexithymic’ are not good at. Their poverty of verbal labels for body sensations related to emotional states is their defining characteristic, and may block necessary processing of experiences in real time. Emotional adjustment and acceptance benefit from review, reflection, hindsight, considering contextual factors, and if possible, ‘normalization’ by an accepting and supportive listener. Pennebaker (2004) has concluded that undisclosed disturbing experiences cause persistent conflict, partly over-suppressing them; the topic stimulates ruminative worry, and this eventually has ill-health effects. Graham et al. (2008) showed that in a large group of chronic pain patients, writing about their anger constructively resulted in better control over both pain and depression, compared with another chronic pain group asked to write about their goals. Junghaenel et al. (2008) also studied the effects of written self-disclosure on chronic pain patients, and found that only those with ‘interpersonally distressed’ characteristics (denoting deficient social support, feeling left alone, etc.) benefited from the expressing of emotional events.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree