Psychological Mechanisms of Tension-Type Headaches

Frank Andrasik

David A. Wittrock

Jan Passchier

Tension-type headache (TTH) can be conceptualized within the framework of Gate Control Theory (25) and its recent extension, Neuromatrix Theory (23). According to these theories, pain is a multidimensional event that includes not just a sensory event, but also cognitive, affective, and behavioral input. Most research on TTH has focused on stress and muscle involvement, and we review these factors in detail. However, the importance of cognitive processing and its emotional consequences has increasingly been recognized as important in the experience of pain, so we also address the contributions of these factors to the experience of TTH. Finally, we devote some attention to the impact of TTH on the patient’s life.

STRESS AS A FACTOR IN TENSION-TYPE HEADACHE

The relationship between stress and TTH has been explored for over 4 decades, and the volume of available research is extensive. The hypothesis that stress is causally related to pain is plausible based on pain theories. Melzack (24) has discussed the integrated relationship between stress and pain in detail. Prolonged activation of the stress system, resulting in high levels of cortisol, is related to a number of physiologic changes that can produce pain. Stress is also directly linked to negative affect, which in turn influences pain (12). Therefore, there are strong arguments for closely investigating the link between stress and chronic pain syndromes.

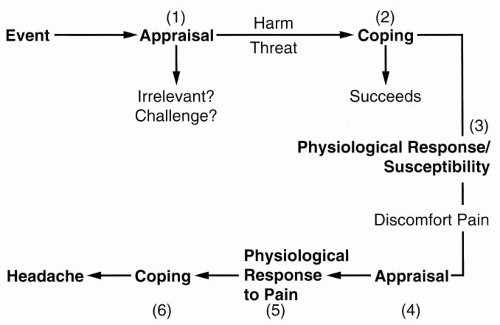

Wittrock and Myers (43) conducted a systematic examination of the empirical literature comparing individuals with recurrent TTH with headache-free controls with respect to stress appraisal and coping and psychophysiologic responses. Their review was guided by a model that incorporates the transactional model of stress (19) and adds to it the role that pain itself plays in the experience of headache, especially when it is of a chronic, unremitting nature (Fig. 74-1). Briefly, the model begins with occurrence of an event that is potentially stressful. Emphasis is on potential because stress is experienced in an idiosyncratic manner; stress rests within an individual’s cognitive interpretive framework. That is, what determines whether any given event is stressful is more a function of how the patient appraises the event. If an event is judged to be both relevant and a threat (step 1 in the model), then a coping response is required (step 2). Unsuccessful attempts at coping lead to physiologic arousal and pain (step 3). Onset of pain can lead to further negative appraisals (step 4), which then intensify attendant pain (step 5), promote further, perhaps more desperate, efforts to cope (step 6), and ultimately exacerbate headache.

Wittrock and Myers (43) theorize that individuals with TTH may differ from nontension headache sufferers in one or more of five different ways. These hypotheses can be stated in a clear and testable manner and are provided in Table 74-1. The brief literature review to follow will discuss how studies have examined these aspects and summarize evidence relating to each hypothesis (drawing upon the observations and conclusions of Wittrock and Myers).

Exposure to Stress

Studies of exposure to stress use scales that focus on distal and/or proximal events. Distal scales typically inquire about major events (positive as well as negative) that have occurred over an extended time period (6 months or more) and that have been assigned a weight indicative of the stress demand. Proximal measures, on the other hand, assess everyday stressors over much briefer time frames (e.g., The Daily Stress Inventory, [8]).

Available studies reveal a fairly consistent picture (43). TTH patients typically do not experience a greater

number of major stressful events over extended time periods; however, TTH sufferers typically do experience a greater number of everyday life stresses (minor ups and downs or hassles) and judge them to have more impact (13,28).

number of major stressful events over extended time periods; however, TTH sufferers typically do experience a greater number of everyday life stresses (minor ups and downs or hassles) and judge them to have more impact (13,28).

FIGURE 74-1. A model for the appraisal and coping process in tension-type headache. (From ref. 43, with permission.) |

Appraisal of Stress

This aspect has been investigated most commonly by presenting various groups of subjects with taxing laboratory tasks (e.g., mental arithmetic, vigilance, items from intelligence tests, and stressful mental imagery). With few exceptions, available research studies have not found headache subjects to report increased stress in response to these stimuli. A few studies have found that TTH subjects reveal higher baseline levels of stress, but any increases are proportional to those exhibited by the nonheadache comparison groups (43). Exposure to identical stressors in controlled laboratory settings leads to similar increases in stress by TTH subjects. However, the salience of the laboratory stressors used may be questioned.

TABLE 74-1 Possible Roles That Stress Might Play With Respect to Tension-Type Headache | |

|---|---|

|

Physiologic Reactivity to Stress

Although research investigations abound in this area (Wittrock and Myers [43] reported nearly 40 such studies in 1998), methodologic complexities have hampered progress. The ideal investigation would (1) examine physiologic responding during adaptation, baseline, stress, and recovery conditions with long time-intervals; (2) include multiple physiologic measures, multiple stress stimuli that simulate real-life circumstances and are personally relevant, multiple comparison groups (carefully matched nonheadache controls and carefully matched other headache types), to permit tests of specificity; (3) conduct assessments when patients were free from headache, when headache was present, and during headache induction; (4) require subjects to abstain from using substances that are known to affect physiology for a set period prior to study entry (e.g., nicotine, caffeine, and medication); and (5) use appropriate measurement and analysis procedures that take gender into account (2). No single study has been able to meet all or even most of these criteria. (Most of these rigorous criteria need consideration when evaluating laboratory investigations of stress appraisal and pain sensitivity and thresholds as well.) Finally, few studies have distinguished between episodic and chronic TTH and none have used the most recently proposed categories (infrequent, frequent, and chronic), and this may be a critical shortcoming (43). In the face of this complexity, it should not be surprising that few findings have been unequivocal or consistently replicated. An earlier review showed promising findings implying increased electromyogram (EMG) responses to stress in patients with recurrent headache (14). A more recent meta-analysis showed that TTH sufferers reveal in the nonheadache state no consistent differences in resting levels or in response to stress (42). However, when headache is present, EMG levels do appear to be more elevated (43). Few studies have realized the importance of tracking headache status at the time that assessments are conducted. Greater attention to this aspect in the future may help to clarify matters.

Sensitivity and Threshold Effects

Investigators have used various stimuli to induce mild pain or discomfort in the controlled laboratory setting: thermal (cold pressor and direct application of ice), pressure (pressure algometer and blood pressure cuff), and other (shock and light). These stimuli have been applied to the head, arm, and finger while various psychophysiologic measures, including assessments of muscle tenderness and subjective or self-report measures (pain intensity, threshold, and tolerance), have been collected (43). Findings here are sometimes complicated and difficult to interpret. With respect to subjective reports, when differences emerge, they are typically of the nature of TTH sufferers

reporting greater sensitivity and a reduced threshold. Analysis of responding in the presence of headache reveals greater pain sensitivity.

reporting greater sensitivity and a reduced threshold. Analysis of responding in the presence of headache reveals greater pain sensitivity.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree