Psychological Assessment and Behavioral Treatment of Chronic Pain

Ronald J. Kulich

Lainie Andrew

The pain of the mind is worse than the pain of the body.

—Publilius Syrus, 1st century BC

I. INTRODUCTION

The role of psychological factors in chronic pain is well established, and minimum standards of care require that physicians address psychosocial factors when managing chronic pain. The overall effectiveness of treatment is often determined by attention to psychosocial issues. Studies have demonstrated that early psychological intervention has a considerable effect on a patient’s reported pain level, ability to cope, activity levels, return to work, and compliance with the medical regimen.

Although there is inherent wisdom in seeking early psychological or psychiatric consultation for complex chronic pain patients, the role of the primary or pain physician should not be underestimated. The treating physician can effectively reinforce positive mood, coping skills, function, and compliance with treatment. Alternatively, the naïve physician may unwittingly reinforce somatic overconcern, helplessness, disability, and lack of patient-perceived control over pain. Although participation of the psychologist or psychiatrist may be necessary, the role of the treating physician and other team members remains pivotal.

Comorbid psychological factors commonly addressed in the literature include anxiety, depression, somatic overconcern, sleep disorder, disability, and substance abuse. Although the exact incidence is debatable, it seems that psychiatric symptoms are present in 50% to 80% of patients with chronic pain. This rate is consistently higher than that reported in the general medical population. There is a growing body of literature supporting the existence of “vulnerabilities” or risk factors that result in a higher likelihood of developing disabling chronic pain. Premorbid vulnerabilities include a history of major depression or anxiety disorder, somatoform disorder, substance use disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder. Poor employment history and job dissatisfaction also have been shown to be predictive of disabling chronic pain. Although the debate persists about the exact role of premorbid psychiatric symptoms in precipitating and maintaining chronic pain, there is little doubt that persistent pain, frustration with ineffective treatment, financial hardship caused by job loss, and other concomitant stressors substantially contribute to the development of psychological symptoms.

II. COMORBID PSYCHIATRIC SYMPTOMS AND DISEASE

1. Anxiety

Anxiety is the most common response to acute pain, and anxiety symptoms often persist when pain becomes chronic. Furthermore, anxiety serves to increase pain perception. Assessment of anxiety can be complicated by drug effects, including withdrawal from opioids or benzodiazepines. Anxiety symptoms commonly occur in specific situations related to fear of activity, injury, work, or social interaction. Although episodic disabling anxiety has been reported to occur in up to 80% of patients with chronic pain, base rates of anxiety in the general population are also high. It has been reported that, each day, primary care physicians see approximately one patient with an anxiety disorder and that approximately 30 million Americans suffer disabling anxiety symptoms.

Particular attention should be paid to patients with a diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder, a condition that often coexists with substance use disorders, depression, and personality disorder. Patients with early childhood abuse histories and/or histories of other serious emotional and physical trauma require formal psychological assessment to maximize adherence to treatment and to improve outcome.

2. Depression

Chronic pain and depression are commonly associated with each other, with a reported 50% incidence of major depression within 5 years of developing a chronic pain disorder. Mortality is high, and suicide has been reported in 10% to 15% of the patients who had prolonged pain and depression. Less severe symptoms of depression have been reported in 80% of the patients with chronic pain. Although it has been argued that studies overestimate depression in the chronic pain population because of an overlap in the symptoms of pain and depression, conservative estimates still exceed the rates in the general population. Investigations have failed to support arguments that improvement in depression

necessarily results in improvement in the affective component of pain, but most practitioners agree that adequate assessment and aggressive treatment of depression benefits the patient with chronic pain.

necessarily results in improvement in the affective component of pain, but most practitioners agree that adequate assessment and aggressive treatment of depression benefits the patient with chronic pain.

3. Sleep Disorders

As with anxiety and depression, sleep disorder symptoms may have multiple causes, including drug side effects. Serious sleep disorders such as sleep apnea can result from a combination of weight gain and polypharmacy. Frequently, the patient complains of “pain waking me from sleep.” However, as with depression, attempts to reduce pain often fail to ameliorate a functional sleep disorder. Depression, anxiety, and poor sleep habits remain the most common cause of sleep disorder in patients with chronic pain. The patient may nap throughout the day and may escape to the bedroom to “rest” during periods of severe pain. Spending many hours lying in bed “trying” to fall asleep complicates the problem, and the patient’s typical sleep schedule remains disrupted by lack of a systematic daily schedule. The typical decrease in physical activity because of chronic pain further compromises sleep. Sleep medications, intended for short-term use, often make the situation worse. Sleep disorders have been shown to exacerbate musculoskeletal pain and contribute to affective disorder. Whether organic or functional, the nature of the sleep complaint requires thorough investigation. Even when sleep disorders are managed pharmacologically, they require concurrent aggressive behavioral treatment.

4. Somatization

Somatization presents another vexing problem for the physician treating pain. Although most patients may not meet formal psychiatric diagnostic criteria for somatization disorder, a thorough assessment may reveal other somatic symptoms dating back many years. Physicians sometimes restrict the focus of their evaluation to the primary presenting problem, often missing a history of multiple somatic complaints. In some cases, patients may intentionally minimize the complexity of their somatic history, whereas a thorough review may reveal a more complex picture. For example, review of the earlier record may reveal a history of fibromyalgia, irritable bowel syndrome, multiple whiplash injuries, noncardiac chest pain, chronic tension–type headache, and/or various pseudoneurologic symptoms reported to other physicians. The history of these complaints can predict a problematic treatment course.

It has been suggested that somatization or “symptom magnification” sometimes occurs because of visits to multiple health care providers who offer conflicting messages about the etiology of the patient’s pain, as well as because of the frustration associated with multiple prior ineffectual treatment trials. The patient may report transient improvements with earlier treatments, with social reinforcement of complaints by family members or health care providers. Reports of improvement or deterioration may not be related to the actual effect of the intervention, whereas the physician may become unwittingly convinced that

the treatment has been effective. The patient then seeks repeated trials of new treatments, with the patient and physician being reinforced after seeing transient gains with each effort. “Disease conviction,” wherein the patients themselves maintain a steadfast commitment to maintaining their somatic preoccupation, is also described.

the treatment has been effective. The patient then seeks repeated trials of new treatments, with the patient and physician being reinforced after seeing transient gains with each effort. “Disease conviction,” wherein the patients themselves maintain a steadfast commitment to maintaining their somatic preoccupation, is also described.

Another construct addressed in the literature is termed “catastrophizing,” wherein the patient obsessively focuses on the myriad of possible negative factors associated with his or her physical condition. The patient with a marked somatic focus cannot accept that there may not be a physical “cure”; “acceptance” of symptoms, by contrast, may be associated with a positive outcome.

5. Malingering

The concept of “malingering” is different from somatization. In the case of malingering, the patient is intentionally feigning symptoms to achieve some gain, often financial gain. Malingering can coexist with documented physical and psychiatric conditions. Although physicians may attest to inconsistencies in the patient’s examination or medical record, they do not always recognize intentional feigning of symptoms. Current evidence does not support the validity of certain strength testing devices and structured interview protocols that were developed in an attempt to identify malingering in the individuals with chronic pain. The validity of these tests in the individuals with chronic pain is questionable, and, currently, there are documented court cases challenging their use. Patients may lie to their physician, but the underlying factors are likely to be complex, and the correct response on the part of the physician is uncertain.

6. Personality Disorders

Although there are numerous types of personality disorders in the standard classification system, no psychiatric disorder presents a greater challenge to a pain physician than borderline personality disorder. Coexisting substance abuse disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, and depression have been widely documented. Compliance issues often become a major theme of the relationship with the treating physician. Patients may loudly praise the skills of physician, whereas the accolades invariably change when the physician fails to meet the patient’s perceived needs. The “relationship” between the physician and patient becomes the “problem,” and the patient may respond with anger and with repeated requests for dose increases and changes in medication. The patients may attempt to enlist relatives and other health care providers to plead their case and arrive for unscheduled visits expecting to be rapidly accommodated. Complaints about other providers are commonplace, and there often is an effort to cause dissention among a treatment team. From a diagnostic perspective, these patients can be identified by their alternating displays of effusive praise for some providers and vehement complaints about the standards of care and medical ethics of others. Such patients are best managed by early clarification of the physician’s circumscribed role and by deference to the primary care physician with respect to coordination of care. Interdisciplinary assessment may aid effective patient management. In addition, concurrent

treatment by a psychologist or psychiatrist is often needed. In fact, these patients can be effectively treated in a structured psychiatric program, whereas a traditional pain center setting often fails to meet their needs.

treatment by a psychologist or psychiatrist is often needed. In fact, these patients can be effectively treated in a structured psychiatric program, whereas a traditional pain center setting often fails to meet their needs.

7. Substance Abuse

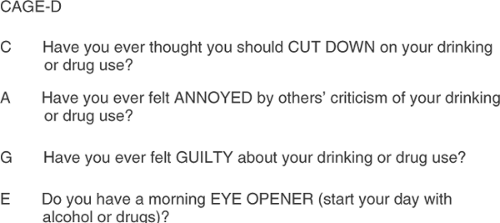

Strong evidence supports the argument that current or past substance abuse predicts poor treatment outcome for a wide range of medical conditions, including chronic pain. Substance abuse occurs in the patients with chronic pain, with reported incidence of 3% to 19%. Studies employing toxic screening or other cross-validation assessments suggest a particularly high incidence in the patients with chronic pain. Physicians have been found to be particularly poor at assessing substance abuse and, therefore, may underestimate the problem. For example, a large study by the Center for Addiction and Substance Abuse found that only 16.9% of physicians were “very prepared” to spot illegal drug use and that only 30.2% were “very prepared” to spot prescription drug abuse. Furthermore, 46.6% of the physicians found it difficult to discuss prescription drug abuse. Forty-three percent of patients reported that their physician did not diagnose their substance abuse problem, 84.9% admitted lying to their physician, and 54.4% had difficulty discussing the issue because they did not want to stop using drugs or alcohol. In view of the poor performance of physicians in assessing substance abuse, formal substance abuse screening, including urine toxicology, should be considered a crucial component of the evaluation. Many pain physicians also employ self-report measures such as the four-item CAGE Questionnaire, which markedly improves their ability to identify the presence of a substance abuse. Figure 1 shows a modified version for assessing drug use. (See also Chapters 31

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree