Introduction

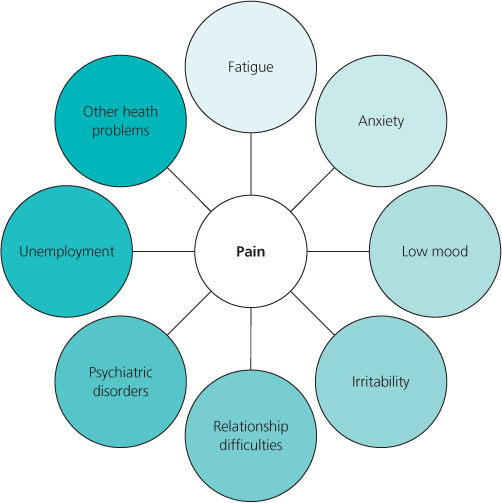

People who experience chronic pain not only have symptoms such as pain, they also experience routinely other symptoms that may bring with them a multitude of other problems (Figure 15.1). In addition to understanding the symptoms and physiological mechanisms of chronic pain, clinicians must also develop an appreciation of the psychological consequences of developing a persistent pain problem.

Early Involvement of Psychology in Pain Management

Early multidisciplinary approaches to chronic pain looked to psychology to provide explanations for the development of pain in persons whose symptoms were unexplained medically. The psychology of the time was influenced heavily by psychoanalytic understandings, which took pain to be an expression of an underlying unconscious conflict. As such, the notion of pain as either organic or ‘psychogenic’ has become widespread. The evidence now suggests overwhelmingly that such a distinction is neither accurate scientifically nor helpful therapeutically. Whilst there are correlational studies that show an association between early life trauma and certain types of pain, such as pelvic pain, there is no convincing evidence that chronic pain arises from a psychogenic causation. Whatever the reason why an individual’s pain persists, psychology is much more useful in explaining how an individual responds to pain and how their behavioural, cognitive and emotional responses influence subsequently both their pain condition and their journey through the healthcare system.

Early work in the field of understanding pain began in earnest with the work of Wilbert Fordyce. He applied the behavioural principles of operant conditioning to explain how certain behaviours (grimacing, complaining of pain, resting) could be shaped by the responses of the pain patient’s significant others. Fordyce reasoned that with repeated shaping of pain responses and reinforcement from others in the form of attention, reduced role burden and so on, the pain response itself became ‘learned behaviour’. Early behaviour analysts used these principles to design behavioural treatments for chronic pain patients that reduced significant other’s responding to maladaptive behaviours, whilst simultaneously increased responding to active behaviours. In addition, behavioural treatment involves establishing collaboratively a series of graded goals and helping the pain sufferer to work towards achieving these goals, step by step.

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy in Pain Management

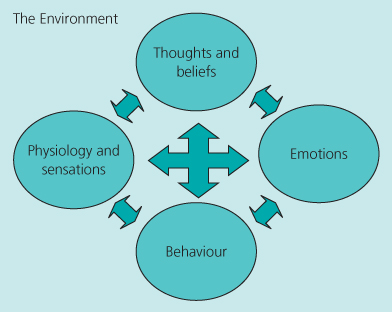

In the 1960s and 1970s the development of computing led to a popularity of cognitive psychology, which attempts to model the processes of thinking, memory, judgement and attention (Figure 15.2). Cognitive psychology and behavioural psychology were blended in the Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) tradition. CBT was first applied successfully in randomised controlled trials to the treatment of major depressive disorder. CBT is now by far the most widely endorsed and practiced form of psychological therapy in the world and it has amassed an impressive evidence base of randomised controlled trials and meta-analyses, demonstrating its effectiveness in treating a wide variety of psychiatric and physical health problems, including chronic pain.

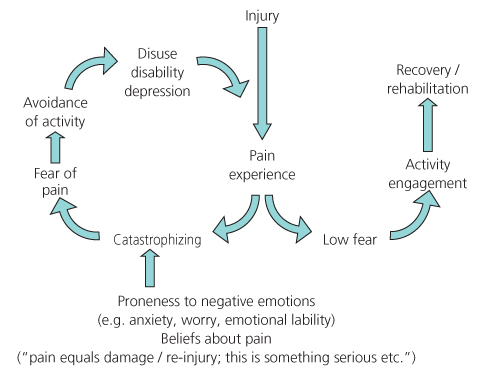

The effectiveness of CBT for chronic pain stems from our understanding of the behavioural, cognitive and emotional consequences of persistent pain, and the consequences of these psychological responses on pain. These factors have been derived from basic and clinical research in the psychology of pain. The most influential understandings of chronic pain have come from The Fear–Avoidance Model (originally proposed by Vlaeyen and co-workers in 1995) (Figure 15.3), catastrophising-based accounts (Sullivan et al., 1995), accounts related to attribution and appraisal (such as from Crombez, and Vlaeyen) (Crombez et al., 1999; Vlaeyen & Linton, 2000) and, more recently, accounts based on Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (as developed by McCracken and co-workers) (McCracken & Eccleston, 2003).

The Fear–Avoidance Model of Chronic Pain

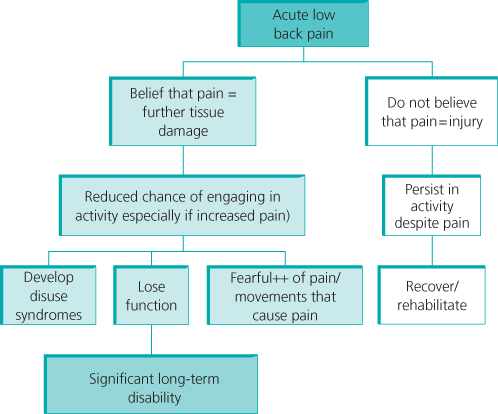

The Fear–Avoidance Model (Figure 15.4) provides a basis for understanding why the degree of disability varies so much among individuals and allows this to be addressed. This may be seen in those patients who believe: ‘Maybe this pain means I am making myself worse’.

Figure 15.4 The Fear–Avoidance Model of chronic pain predicts that the primary difference between individuals who recover or rehabilitate successfully from an experience of acute low back pain and those do not, are the beliefs they hold and the behaviours that flow from these beliefs.

As fear of pain develops, the individual develops an attentional focus on pain, increased arousal, reduced activity and further catastrophic misinterpretation of pain sensations as signalling damage. As a result of reduced activity and a seemingly inescapable pain problem, individuals will be more likely to develop mood problems, which alter the threshold at which pain sensations will be perceived and responded to.

There is now significant evidence for each of the basic elements of the Fear–Avoidance Model in chronic low back pain. There is also evidence of pain-related beliefs, fear of pain and avoidance of pain being predictive of the development of low back pain disability, independent of pain intensity.

Pain Catastrophising

An important element of the Fear–Avoidance Model is catastrophic misinterpretation of pain sensations (Figure 15.5). Catastrophising can be measured readily using standardised self-report questionnaires and is thought to be a relatively stable dispositional trait. It has been shown to correlate highly with most important indices of functioning, including pain intensity, disability, distress, mood problems, quality of life, observable pain behaviour, spousal responding and activity avoidance. In addition, several prospective studies have demonstrated associations between initial levels of catastrophising and subsequent experiences of pain after surgery, pain during a painful procedure and in long-term adjustment to lower limb amputation.