Psychological and Behavioral Treatments of Migraines

Patrick J. McGrath

Donald Penzien

Jeanette C. Rains

Over the past three decades, several widely used behavioral interventions for migraine headache have been shown to be effective (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6). In most instances these interventions emphasize prevention of headache episodes as opposed to aborting acute headache. Although behavioral modalities can be highly effective as monotherapy, they are more commonly used in conjunction with pharmacologic management.

Behavioral interventions are particularly well suited for headache patients with (a) poor tolerance of pharmacologic treatments; (b) contraindications for medications; (c) insufficient response to pharmacologic treatments; (d) patient preference for nonpharmacologic treatment; (e) pregnancy, planned pregnancy, or nursing; (f) history of frequent or excessive use of analgesic or other acute medications that can aggravate headache problems (or decreased responsiveness to other pharmacotherapies), and (g) significant stress or deficient stress-coping skills. However, many patients who benefit from psychological and behavioral treatment have no psychological or behavioral deficiencies. The long-term goals of behavioral headache therapies include (a) reduced frequency and severity of headache; (b) reduced headache-related disability; (c) reduced reliance on poorly tolerated or unwanted pharmacotherapies; (d) enhanced personal control of headache; and (e) reduced headache-related distress and psychological symptoms.

The most extensively researched and most frequently used interventions fall into three categories: relaxation training, biofeedback (often administered in conjunction with relaxation training), and stress-management training (cognitive-behavioral therapy). The resources necessary for implementation of these therapies (e.g., trained clinicians, biofeedback equipment) are not always readily available. To facilitate dissemination of these interventions, the World Health Organization has released the monograph Self-management of Recurrent Headache as a part of their series of behavioral science learning modules for the health professions. The monograph presents a “lowtech” approach to behavioral headache therapy that can be readily implemented by generalist healthcare providers with minimal resources (2).

RELAXATION TRAINING

The therapeutic value of relaxation training has been recognized for over 100 years (7,8). During the past three decades, three types of relaxation training have become widely accepted as a standard treatment for headache: (a) progressive muscle relaxation—alternately tensing and relaxing selected muscle groups throughout the body (9, 10, 11, 12); (b) autogenic training—the use of self-instructions of warmth and heaviness to promote a state of deep relaxation (13); and (c) meditation or passive relaxation—use of a silently repeated word or sound to promote mental calm and relaxation (14). The development of relaxation skills presumably enables headache sufferers to exert greater control over headache-related physiologic responses and, more generally, to lower sympathetic arousal. Relaxation training may also provide a retreat from daily stressors as well as assist patients to gain a sense of mastery or self-control over their symptoms. A relaxation training protocol may consist of 10 or more treatment sessions, with many clinicians using fewer sessions when treating uncomplicated headache conditions. During treatment, patients typically are instructed to practice relaxation daily at home, with audiotapes provided to facilitate practice.

BIOFEEDBACK TRAINING

The two types of biofeedback training most often employed in the treatment of recurrent headaches are hand warming or thermal biofeedback—feedback of skin

temperature from a finger—and electromyographic (EMG) biofeedback—feedback of electrical activity from muscles of the forehead, scalp, neck and sometimes the upper body (1,15). Other types of biofeedback training (e.g., cephalic vasomotor, electrodermal) are more challenging to administer and are not widely used with headache. Biofeedback training for headache is commonly administered in conjunction with relaxation training either concurrently or sequentially, and may require a dozen or more treatment sessions. As with relaxation training, patients typically are instructed to practice self-regulation skills at home daily during treatment.

temperature from a finger—and electromyographic (EMG) biofeedback—feedback of electrical activity from muscles of the forehead, scalp, neck and sometimes the upper body (1,15). Other types of biofeedback training (e.g., cephalic vasomotor, electrodermal) are more challenging to administer and are not widely used with headache. Biofeedback training for headache is commonly administered in conjunction with relaxation training either concurrently or sequentially, and may require a dozen or more treatment sessions. As with relaxation training, patients typically are instructed to practice self-regulation skills at home daily during treatment.

STRESS MANAGEMENT TRAINING AND COGNITIVE-BEHAVIORAL THERAPY

The rationale for cognitive-behavioral therapy or stress-management training in headache management derives from the observation that the way individuals cope with everyday stressors can precipitate, exacerbate, or maintain headaches and increase headache-related disability and distress (16, 17, 18). Cognitive-behavioral therapy focuses on the cognitive and affective components of headache, and it is typically administered in conjunction with relaxation or biofeedback training that focuses on the physiologic components of headache.

Cognitive-behavioral interventions alert patients to the role of cognitions in stress responses and the relationships between stress, coping, and headache. Patients are taught to identify the specific psychological or behavioral factors that trigger or aggravate their headaches, and to employ more effective strategies for coping with headache-related stress. By assisting patients to more effectively manage stress, cognitive-behavioral therapy can limit the disability, anxiety, and depression that often afflicts patients with more frequent and severe headaches. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for headache commonly requires from 3 to 12 or more treatment sessions. Clearly, greater psychotherapeutic skill is required to administer cognitive-behavioral therapy than to administer relaxation training or biofeedback training.

Effectiveness of Behavioral Treatments

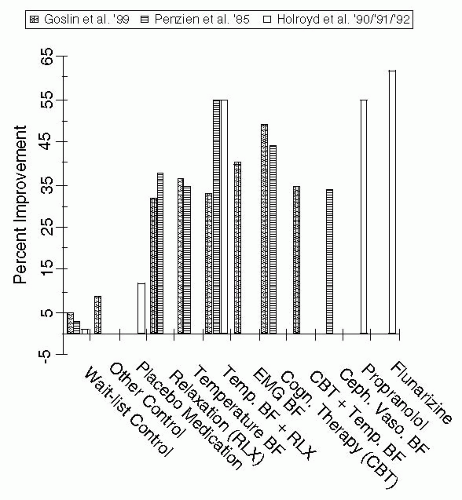

A number of meta-analytic reviews have summarized the empirical evidence examining the effectiveness of behavioral interventions for migraine (19, 20, 21, 22). The most recent was an exhaustive review by Goslin et al. (23) undertaken with support from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) and employing highly conservative study inclusion criteria. The literature search identified 355 articles describing behavioral and physical treatments for migraine, of which 70 reported controlled clinical trials of behavioral treatments for migraine in adults. The 39 prospective and randomized trials that met all of the stringent research design and data extraction requirements yielded 60 treatment groups in the following categories: relaxation training, temperature biofeedback training, temperature biofeedback plus relaxation training, EMG biofeedback training, cognitive-behavioral therapy (stress-management training), cognitive-behavioral therapy plus temperature biofeedback, wait list control, and other controls. Treatment outcome data were calculated using two metrics: summary effect size estimates and mean percentage headache improvement from pre- to posttreatment. These behavioral interventions yielded 32 to 49% reductions in migraine versus 5% reduction for no-treatment controls (Fig. 48-1). The effect size estimates indicated that relaxation training, thermal biofeedback combined with relaxation training, EMG biofeedback, and cognitive-behavioral therapy were all statistically more effective than wait list control.

The AHRQ-sponsored meta-analysis (23) is the only empirical review of the migraine literature to employ highly selective study inclusion criteria. Each of the earlier meta-analyses were broadly inclusive of all available research (19, 20, 21, 22). Findings of the other meta-analyses nevertheless closely parallel the AHRQ review indicating that

behavioral treatments for migraine headache are effective (35 to 55% improvement), and all treatments are more effective than control conditions (see Fig. 48-1).

behavioral treatments for migraine headache are effective (35 to 55% improvement), and all treatments are more effective than control conditions (see Fig. 48-1).

There is a sizeable amount of evidence indicating that, at least among those who respond initially, the effects of behavioral treatments endure over time, with the longest follow-up occurring 7 years posttreatment (22,24). For example, Blanchard et al. (25) found that 91% of migraine headache sufferers remained significantly improved 5 years after completing behavioral headache treatment.

An evidence-based practice guideline based on AHRQ technical reviews of the evidence has now been forwarded by a multidisciplinary consortium (U.S. Headache Consortium) (26,27). The organizations comprising the consortium included the American Academy of Family Physicians, American Academy of Neurology, American Headache Society, and the American College of Physicians, among others. The Consortium’s recommendations pertaining to behavioral interventions for migraine are (a) relaxation training, thermal biofeedback combined with relaxation training, EMG biofeedback, and cognitive-behavioral therapy may be considered as treatment options for prevention of migraine (Grade A Evidence), and (b) behavioral therapy may be combined with preventive drug therapy to achieve added clinical improvement for migraine (Grade B Evidence) (28).

ALTERNATE TREATMENT FORMATS FOR BEHAVIORAL INTERVENTIONS

In the 1980s, researchers became increasingly aware of drawbacks to intensive clinic-based and individually administered behavioral treatment delivery models and began to consider issues of cost and efficiency. Minimal therapist contact treatments, group treatment, and some novel mass communication treatment formats have emerged to increase accessibility or reduce costs of behavioral treatments.

Minimal Therapist Contact Treatment

In a minimal-contact or “home-based” intervention, self-regulation skills are introduced in the clinic, but training primarily occurs at home with the patient guided in part by printed materials and audiotapes. Consequently, only three or four clinic sessions may be necessary when behavioral techniques are delivered via this format versus the eight or more weekly clinic sessions required for the standard clinic-based format. Three meta-analyses of minimal-contact behavioral interventions for headache have consistently demonstrated the utility of this approach, indicating that for many patients such treatments can be as effective as those delivered in a clinic setting (6,29,30) (Fig. 48-2).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree