Chapter 4 Provocation Discography

Patient selection is of the utmost importance. This includes an appropriate history, physical examination, and interpretation of a recent MRI or CT scan by the physician performing the discography.

Patient selection is of the utmost importance. This includes an appropriate history, physical examination, and interpretation of a recent MRI or CT scan by the physician performing the discography. The discographer must be experienced and skilled in needle placement, and understand the intricacies of the procedure.

The discographer must be experienced and skilled in needle placement, and understand the intricacies of the procedure. Informed consent is necessary to ensure that the patient understands and is comfortable with the provocative nature of the procedure and the need to provide appropriate information and dialogue with the physician.

Informed consent is necessary to ensure that the patient understands and is comfortable with the provocative nature of the procedure and the need to provide appropriate information and dialogue with the physician. High quality fluoroscopic equipment and procedure table allow good visualization and safe disc access.

High quality fluoroscopic equipment and procedure table allow good visualization and safe disc access. Sedation should be used only to the extent as to provide adequate comfort for the patient without compromise of the pain responsiveness.

Sedation should be used only to the extent as to provide adequate comfort for the patient without compromise of the pain responsiveness. Use a true anterioposterior view with the endplate closest to the target parallel to the x-ray beam and appropriate obliquity, unique for each disc level accessed.

Use a true anterioposterior view with the endplate closest to the target parallel to the x-ray beam and appropriate obliquity, unique for each disc level accessed. Pain produced ipsilaterally to the needle insertion site must be evaluated carefully. The needle can be jiggled gently to distinguish needle pain from discogenic pain.

Pain produced ipsilaterally to the needle insertion site must be evaluated carefully. The needle can be jiggled gently to distinguish needle pain from discogenic pain. Transient pain may be provoked. A true positive response is concordant pain, ≥7/10, sustained for greater than 30 to 60 seconds, at a pressure of ≤50 psi above opening, and volume of ≤3.5 mL.

Transient pain may be provoked. A true positive response is concordant pain, ≥7/10, sustained for greater than 30 to 60 seconds, at a pressure of ≤50 psi above opening, and volume of ≤3.5 mL. Discography performed at levels of prior discectomy have a higher false-positive response rate, and low pressure and volume criteria must be upheld.

Discography performed at levels of prior discectomy have a higher false-positive response rate, and low pressure and volume criteria must be upheld. If the patient has significant pain in a disc without a grade 3 tear, consider pain referred from a contiguous disc, overlap of innervations, or a fissure too small to discern by fluoroscopy.

If the patient has significant pain in a disc without a grade 3 tear, consider pain referred from a contiguous disc, overlap of innervations, or a fissure too small to discern by fluoroscopy. All positive responses should be confirmed with manual repressurization with a small volume. If repressurization does not provoke concordant ≥7/10 pain at <50 psi a.o., the response is considered indeterminate.

All positive responses should be confirmed with manual repressurization with a small volume. If repressurization does not provoke concordant ≥7/10 pain at <50 psi a.o., the response is considered indeterminate. If the patient provokes pain in a disc without a grade 3 tear, (adjacent to a positive response disc) one mL of 4% lidocaine (Xylocaine) should be injected into the painful adjacent disc and provocation testing repeated in about 5 minutes. One may find that the normal-appearing disc is no longer painful. If still painful, one should look for a small annular tear on the post-discogram CT scan.

If the patient provokes pain in a disc without a grade 3 tear, (adjacent to a positive response disc) one mL of 4% lidocaine (Xylocaine) should be injected into the painful adjacent disc and provocation testing repeated in about 5 minutes. One may find that the normal-appearing disc is no longer painful. If still painful, one should look for a small annular tear on the post-discogram CT scan. Pain produced ipsilaterally to the needle insertion site must be evaluated carefully. Referred pain may be caused by the discogram needle adjacent to the dorsal root ganglion. The needle can be jiggled gently to distinguish needle pain from discogenic pain.

Pain produced ipsilaterally to the needle insertion site must be evaluated carefully. Referred pain may be caused by the discogram needle adjacent to the dorsal root ganglion. The needle can be jiggled gently to distinguish needle pain from discogenic pain. Transient pain may be provoked if an asymptomatic fissure or previously healed annular tear with a fibrous cap is opened abruptly during pressurization. A true positive pain response is ≥7/10 and sustained for greater than 30 to 60 seconds; true discogenic pain is less likely to decrease rapidly. Pain that resolves within 10 seconds should be discounted. Clinically, patients with discogenic pain tend to have increased pain post procedure, and may note some exacerbation of symptoms for 3 to 7 days.

Transient pain may be provoked if an asymptomatic fissure or previously healed annular tear with a fibrous cap is opened abruptly during pressurization. A true positive pain response is ≥7/10 and sustained for greater than 30 to 60 seconds; true discogenic pain is less likely to decrease rapidly. Pain that resolves within 10 seconds should be discounted. Clinically, patients with discogenic pain tend to have increased pain post procedure, and may note some exacerbation of symptoms for 3 to 7 days. False positive pain provocation will occur in a severely degenerated disc if excessive volume is injected. Injected volume should be limited to about 3.5 mL if the disc has an intact annulus or the disc is so degenerated that more volume is needed to fill the disc.

False positive pain provocation will occur in a severely degenerated disc if excessive volume is injected. Injected volume should be limited to about 3.5 mL if the disc has an intact annulus or the disc is so degenerated that more volume is needed to fill the disc.Introduction

Until the introduction of discography by Lindblom in the 1940s and 1950s,1–3 oil-based contrast myelography was used to diagnose intervertebral disc herniations.4 During the era of the “herniated disc” in the 1930s,5 both axial and referred pain were thought to be caused by the disc-compressing neural elements. Myelography has always been limited in that it only visualized the thecal sac and dural root sleeves. Discography allowed visualization of the disc itself, including internal morphology and lateral protrusions, which were missed on myelography.

Discography was initially used to diagnose disc herniations before surgery in patients with radicular pain.1,6,7 Interestingly, however, most of the discs examined by discography exhibited annular disruption but no frank herniation or protrusion. More important, on injection of contrast media into these internally disrupted discs, some patients experienced reproduction of their familiar pain.8,9 These observations led surgeons to use provocation discography not only to reveal structural abnormalities but also to identify and treat painful internally disrupted discs. Discography became a sophisticated extension of the physical examination, a means of “palpating” the disc to elicit pain.10

Over the last decades histochemical and anatomical studies have provided evidence that the disc is an innervated structure capable of transmitting pain. There is no doubt that the disc can be a source of pain. Typically in a normal disc innervation is limited to the outer annulus; however, we know that pathologically painful discs (based on positive discogram pre-fusion) show neoinnervation to the inner annulus and nucleus pulposus.11–13 It is believed that injection of contrast dye into the nucleus stimulates nerve endings14 via two mechanisms: a chemical stimulus from contact between contrast dye and sensitized tissues and a mechanical stimulus resulting from fluid-distending stress. What is controversial is not whether the disc is a source of pain but whether disc pain can be reliably diagnosed. The validity and accuracy of discography has been challenged, particularly in the last 10 years, with reports of unacceptably high false-positive rates in asymptomatic subjects, particularly in patients with chronic pain or evidence of psychological pathology. However, these negative studies have been refuted after close review and a performance of a meta-analysis of false-positive rates of lumbar discography. Combining all the major studies on discography in asymptomatic subjects, a false-positive rate of less than 10% can be achieved if the discographer adheres to strict operational standards and interpretation criteria.15

Although magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) are the most commonly used advanced imaging modalities for low back pain, discography still occupies a critical place in the diagnostic algorithm. We know that abnormal disc morphology alone is not diagnostic of discogenic pain because many individuals with abnormal CT scans or MRIs are asymptomatic of low back pain.16,17 However, MRI cannot distinguish between a painful and painless disc. In contemporary practice the criterion standard for diagnosis of a painful internally disrupted disc by provocation discography is pain ≥7/10, pressure <50 psi a.o. (pounds per square inch above opening), concordant pain, ≥grade 3 annular tear, volume ≤3.5 mL, and the presence of a negative control disc.18

In this chapter the indications for discography, both technical considerations and complications of lumbar discography, are discussed. Procedural descriptions have also been extensively described in our prior publications.19–21 The technical section of the chapter is followed by a brief updated literature review regarding the role of discography as a diagnostic test (vs. MRI and CT), the false-positive controversy, and both predictive value and analgesic discography.

Indications and Contraindications

Discography is not an initial screening examination. Disc stimulation follows failed conservative treatment modalities and is only used when other less invasive diagnostic tests are inconclusive. Discography is invasive, and irreversible surgical procedures may be chosen based on the results. The principal indication for provocation discography is to determine whether or not a disc is pathologically painful and the extent of annular or endplate disruption. Pertinent clinical information is then used to establish a diagnosis of discogenic pain for targeted disc therapies. Only discography followed by CT scanning can define the internal anatomy of the disc.22 Postdiscography CT scanning is also particularly useful in postdiscectomy patients with suspected residual or recurrent disc herniations. Discography is useful in problematic cases unresolved by MRI or myelography and in patients for whom surgery is contemplated.23 It can offer a potential solution to the diagnostic dilemma concerning which patients to treat surgically and at what segmental level. When a single disc is found to be symptomatic in the presence of adjacent asymptomatic discs, focused intradiscal or surgical therapy can be entertained. A no less important application is to identify discs which are non-pristine by imaging studies, but are asymptomatic, and therefore require no treatment intervention.

The position statement of the North American Spine Society on discography is as follows:22 Discography is indicated in the evaluation of patients with unremitting spinal pain, with or without extremity pain, of greater than 4 months’ duration, when the pain has been unresponsive to all appropriate methods of conservative therapy. Before discography the patients should have undergone investigation with other modalities that have failed to explain the source of pain; such modalities should include but not be limited to CT scanning, MRI scanning, and/or myelography.

Indication criteria include the following:

The patient is capable of understanding the nature of the technique and can participate in the subjective interpretation.

The patient is capable of understanding the nature of the technique and can participate in the subjective interpretation.Contraindications include the following:

Relative contraindications to discography follow:

Preprocedure Evaluation

Specifically the patient should understand that discography is commonly painful and that they will need to describe the location, intensity, and concordance of any provoked pain in respect to their ongoing complaints. A trained observer can independently monitor patient pain responses during the procedure. Some discographers have their patients fill out a brief psychometric test such as the Distress and Risk Assessment Method (DRAM) to assess if the patient has a normal, at risk, distressed depressive, or distressed somatic profile.24

In patients with a history of allergy to nonionic water-soluble contrast media (iohexol or iopamidol) or other drugs, the risks vs. benefits of the procedure must be weighed and discussed with the patient. Patients with suspect iodine allergies should be pretreated with corticosteroids and H1 and H2 blockers before the procedure. If the risk of allergic reaction to contrast is significant, saline can be substituted with the addition a very small volume of gadolinium considered. The addition of gadolinium allows assessment of the internal disc by MRI performed immediately post-procedure.25,26

Patient Preparation

Antibiotic Prophylaxis

Intravenous (IV) access is standard. Discitis is the most common serious (although rare) complication. Prophylactic antibiotic (cefazolin 1 g, gentamicin 80 mg, clindamycin 900 mg, or ciprofloxacin 400 mg) is given within 30 minutes of needle insertion. Sheep studies confirmed optimal antibiotic levels in the annulus 30 minutes after IV administration; no antibiotics were present at 60 minutes.27,28 Following the procedure aminoglycosides are not required for prophylaxis.29 Along with IV antibiotics, many discographers mix antibiotics with the contrast dye (between 1 and 6 mg/mL of cefazolin or an equivalent dose of another antibiotic) for intradiscal administration.30–33 Klessig, Showsh, and Sekorski33 reported that cefazolin and gentamicin, 1 mg/mL; and clindamycin, 7.5 mg/mL, exceed the minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) for the three most common organisms causing discitis: Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, and Staphylococcus epidermidis. All procedures should be performed under sterile conditions with double gloves. Another concern is patients with histories of surgical infection who are methicillin-resistant S. aureus carriers. Preoperative nasal cultures have been used to identify carriers and treated with mupirocin topical to nares with reduction in surgical infection.

Sedation

Some discographers, including one of the authors (MHL), believe that opioids should not be used before or during discography.21,34–36 They assert that discography is a provocational test; therefore pain intensity needs to be compared and quantified in relation to the patient’s usual pain intensity, and opioid analgesics could decrease the pain response and increase the chance of a false-negative response. Alternatively, others32 believe that a small dose of analgesics (meperidine [Demerol], 50 mg; fentanyl, 50 mcg; or morphine, 5 mg) before the procedure helps to decrease the rate of false positives in patients with clinically insignificant discogenic pain.

Sterile Technique

Chlorhexidine and alcohol may be substituted if the patient has allergies to the aforementioned solutions. Recent studies37 suggest that chlorhexidine and alcohol preparation are superior to povidone-iodine solution in reducing postoperative infection. Other suggested protocols may include a chlorhexidine shower the night before the procedure. Some authors scrub the area of the procedure before sterile preparation. This is done to remove the top layer of grime and material that may be hoarding skin bacteria. The procedure room staff should be dressed in clean clothes (scrub suits). Surgical caps and masks are mandatory for any personnel in close contact to the sterile field. Many injectionists scrub, gown, and glove as for an open surgical procedure. The C-arm image intensifier should also be draped to prevent detritus from falling onto the sterile field, and allows the injectionist to easily position the instrument for optimum visualization using safe, sterile technique.

Disc Puncture

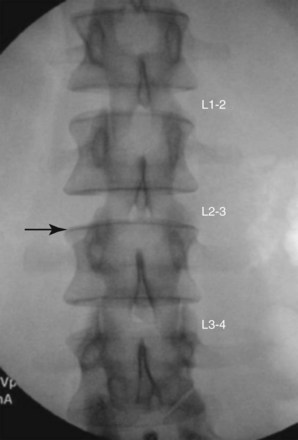

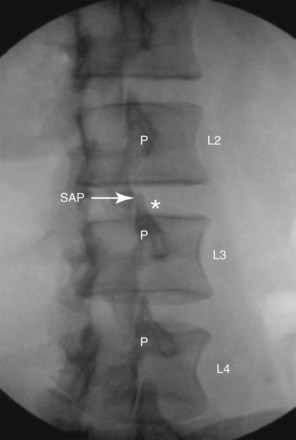

Until the 1960s discography was performed with a posterior interpedicular or transdural approach; however, this technique is seldom used today because it requires two punctures of the dura. Currently a lateral, or extrapedicular, approach38,39 is used, except in rare situations in which anatomical variation or postsurgical changes prevent disc access from a lateral approach. Before injection a fluoroscopic examination of the spine is performed to confirm segmentation and determine the appropriate level for needle placement. The target disc is identified on AP view. The image intensifier of the C-arm is tilted in a cephalad or caudad direction until the endplate of the vertebral body, caudad to the target disc, is parallel to the x-ray beam (Fig. 4-1). The endplate is visualized as a line rather than an oval. After selecting the target disc on AP view, the fluoroscopic beam is rotated obliquely until the superior articular process of the facet joint is at the midpoint of the upper vertebral endplate. On occasion at L5-S1, due to the wider dimension of the vertebral body, increased interfacetal distance, and the iliac crest, the fluoroscopy tube can only be rotated far enough to bring the SAP approximately 25% of the distance between the lateral margins of the inferior endplate of the level above. In this oblique view the insertion point is 1-3 mm lateral to the lateral margin of the superior articular process (SAP) (Fig. 4-2). This positioning of the fluoroscope allows needles to be passed using tunnel vision (i.e., parallel to the beam when the skin puncture site is aligned with the target structure) just lateral to the SAP. The disc is preferentially approached from the side opposite the patient’s usual pain to avoid the patient mistaking discomfort secondary to needle placement with provoked pain secondary by disc stimulation. If the patient has central pain or the pain is equal bilaterally or if there are other impeding technical factors, needle insertion from either side is fine.

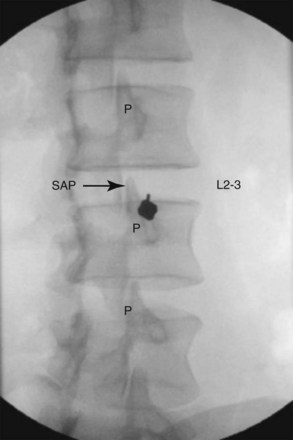

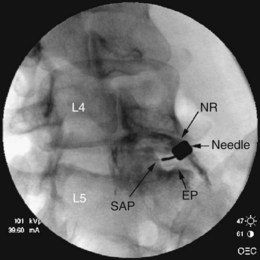

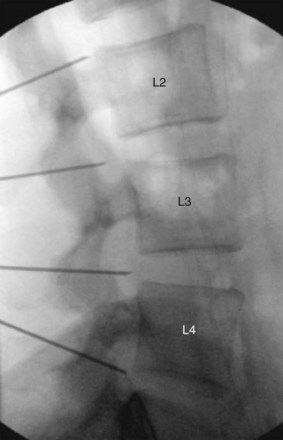

Before needle placement a skin wheal is made with lidocaine 1% (≈1 mL) using a 25-gauge, 1.5-inch needle. To anesthetize the needle track, one can use a 25-gauge, 3.5-inch needle advanced under tunnel vision (i.e., parallel to the x-ray beam to the level of the SAP). Exercise caution so as not to anesthetize the dorsal root ganglion within the foramen. Overenthusiastic anesthetization may obscure nerve root impalement and could potentially anesthetize the sinuvertebral and ramus communicans nerves, thus altering the evoked pain response during disc stimulation and creating a false-negative response. A one- or two-needle technique may be used; however, most discographers currently use a two-needle technique. Before the routine use of prophylactic antibiotics, Fraser, Osti, and Vernon-Roberts40 reported a rate of discitis with single nonstyleted vs. double needles of 2.7% vs. 0.7%. Both the North American Spine Society and the International Spinal Injection Society recommend a two-needle approach.18,22 The two-needle technique uses a shorter, larger-gauge introducer needle through which a longer, smaller-gauge needle is advanced past the tip of the introducer needle into the targeted intervertebral disc, theoretically avoiding picking up any skin flora.. The trend is to use a 20-gauge, 3.5-inch introducer with the 25-gauge, 6-inch disc puncture needle. The 25-gauge needle theoretically minimizes any trauma to the disc. Less experienced operators may start with the 18/22-gauge needle combination, particularly because the curve of the disc puncture needle is easier to maintain. The body habitus of the patient will dictate if longer needles are necessary (i.e., a 5-inch introducer and an 8-10-inch disc puncture needle). A slight bend, opposite the bevel, is typically made at the tip of the disc puncture needle to allow the operator to “steer” the needle.41–44 At times a larger curve, at the distal third of the disc puncture needle, must be used to compensate for less than ideal anatomy or postsurgical changes. The introducer needle is passed through the skin wheal at the skin puncture point, using a “down the beam” or tunnel-vision technique on the oblique fluoroscopic view (Fig. 4-3). To avoid potential neural injury, the needle should be directed into the region below the segmental nerve, just lateral to the superior articular process and above the endplate (Figs. 4-3 and 4-4). The disc puncture needle must travel under the segmental nerve coursing medial to lateral and dorsal to ventral to puncture the annulus fibrosus of the disc at the midpoint of the disc when seen in lateral and AP views. To minimize nerve trauma, a needle with a short, noncutting bevel or blunt pointed tip with a side port might be considered. Forward advancement is stopped at the approximate level of the SAP, although placement within the dorsal foramen is acceptable. A lateral fluoroscopic view should be used to check needle depth (Fig. 4-5).

The stylet is then removed from the introducer; and the longer, smaller-gauge disc puncture needle is advanced slowly under real-time lateral fluoroscopy. The needle is seen to transverse the intervertebral foramen; then firm but resilient resistance is noted as the needle touches and punctures the annulus fibrosus. On the lateral view the needle typically contacts the posterior disc margin 1 to 3 mm posterior to the vertebral margin. On AP projection the discogram needle ideally contacts the disc margin on a line drawn between the midpoints of the pedicles above and below (Fig. 4-6). The patient may experience a brief sharp, pinching, or sudden aching sensation when the needle pierces the innervated outer annulus fibrosus. In no case should one advance the introducer or discogram needle medial to the inner pedicle margins before contacting the intervertebral disc. Using lateral fluoroscopy, the needle is then advanced to the center of the disc as seen on both lateral and AP projections (Figs. 4-7 and 4-8

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree