CHAPTER 25 Prolotherapy

Description

Terminology and Subtypes

Intraligamentous injection of solutions aimed at promoting connective tissue repair is commonly known as prolotherapy, which has been defined as “the rehabilitation of an incompetent structure (such as a ligament or tendon) by the induced proliferation of new cells.”1 Common synonyms for this intervention include regenerative injection therapy, growth factor stimulation injection, nonsurgical tendon, ligament and joint reconstruction, proliferant injection, prolo, and joint sclerotherapy.2 Proponents of this intervention generally dislike the term sclerotherapy, which is associated with the formation of unorganized scar tissue rather than the organized connective tissue that prolotherapy is intended to generate.3,4

Although there are no formal subtypes of prolotherapy, there is substantial heterogeneity in the treatment protocols used by different practitioners. The approaches to prolotherapy generally differ according to the type of solution injected, the volume and frequency of injections, and use of cointerventions. The method used in studies by Ongley and colleagues typically involves six weekly injections of 20 to 30 mL of a solution containing dextrose 12.5%, glycerin 12.5%, phenol 1%, and lidocaine 0.25% into multiple preselected lumbosacral ligaments.5,6 Injections are usually accompanied by spinal manipulation therapy (SMT) and instructions for the patient to perform repeated standing lumbar flexion-extension exercises for several weeks. This approach may also use corticosteroid injections into tender lumbosacral areas before the first session of prolotherapy. This approach has occasionally been termed the Ongley approach or West Coast approach.

Prolotherapy methods used in other studies involved a greater number of injections at longer intervals (biweekly to monthly) with a smaller gauge needle, a lower injected volume (10 to 20 mL), and a solution containing only dextrose 10% to 20% and lidocaine 0.2% to 0.5%.5–10 The rationale provided by proponents of this latter method is that it minimizes the inflammatory reaction and is therefore more easily tolerated by patients with severe pain. It should be noted that all methods of prolotherapy were developed clinically based largely on anecdotal evidence. Practitioners often further modify these interventions and cointerventions according to perceived patient needs.

History and Frequency of Use

Prolotherapy has been used to treat chronic low back pain (CLBP) for more than 60 years and was originally adapted from sclerotherapy, which involves injection of irritant solutions to induce acute inflammation, stimulate connective tissue growth, and promote formation of collagen tissue.7,11 Sclerotherapy was commonly used to close the lumen in varicose veins, and in nonsurgical abdominal hernia repair.8 Based on the hypothesis that joint hypermobility could be attributed to incomplete connective tissue repair after an injury (similar to hernias), this treatment approach was later applied to chronic musculoskeletal conditions suspected of being related to ligament or connective tissue laxity. The use of prolotherapy for CLBP was promoted in the 1950s by a surgeon named George S. Hackett, who published large case series claiming very high rates of success for a condition that had few effective surgical options at that time. A survey of 908 primary care patients receiving opioids for chronic pain, most commonly CLBP (38.4%), reported that 8.3% had used prolotherapy in their lifetime and that 5.9% had used it in the past year.9 Those who reported using prolotherapy had an average of 3.5 injections in the past year, which corresponds with some of the commonly used protocols recommending injections every few months to achieve maximum benefits.

Practitioner, Setting, and Availability

Prolotherapy is mainly administered by medical or osteopathic physicians, although in rare instances a physician’s assistant, nurse practitioner, or naturopath can administer injections where state licensure permits.12 Practitioners who perform this treatment are expected to have advanced knowledge of spinal anatomy, including the attachment points for all connective tissue structures that may be injected, and the locations of any surrounding blood vessels or nerves that may be inadvertently injected. Extensive experience with spinal injections is usually recommended before learning prolotherapy and many clinicians who perform these treatments also have specialized training in anesthesiology, pain management, or physical medicine and rehabilitation.12

Additional postgraduate training specifically in prolotherapy is typically offered through continuing medical education courses sponsored by related organizations and medical schools, including the University of Wisconsin. Organizations involved in prolotherapy training include the American Association of Orthopaedic Medicine (AAOM), American College of Osteopathic Sclerotherapeutic Pain Management (ACOSPM), Hackett Hemwall Foundation, and American Institute of Prolotherapy.13–16

Procedure

The treatment procedure for prolotherapy varies a great deal among practitioners. The treatment typically begins with a thoroughly focused musculoskeletal history and physical, neurologic, and provocative manual examination of the area of complaint and surrounding joints and muscles. Once the assessment is completed and target structures are identified as amenable to prolotherapy injections, treatment may begin. For CLBP, treatment is usually conducted while the patient wears a medical gown and lies prone on a treatment table. Through manual palpation, the physician first identifies—and possibly indicates with a skin marker—anatomic landmarks in the lumbosacral spine area such as the iliac crest, sacroiliac (SI) joints, and intervertebral spaces to use as reference points for the injections. The skin is then cleaned with alcohol and betadine to minimize the risk of infection. Some practitioners first inject subcutaneous wheals of local anesthetic into the targeted areas to minimize patient discomfort.6

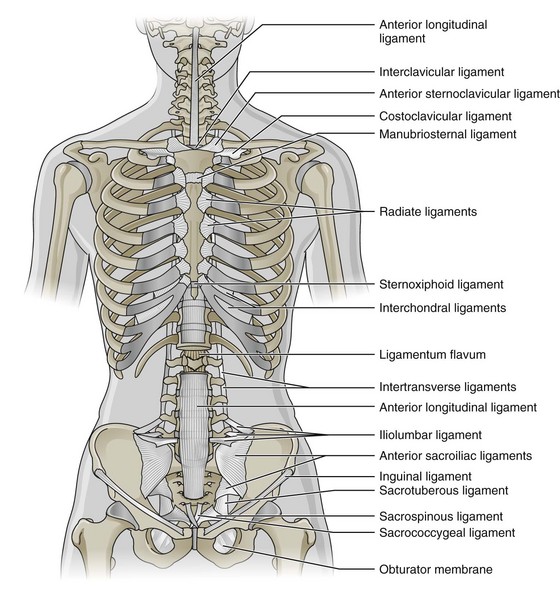

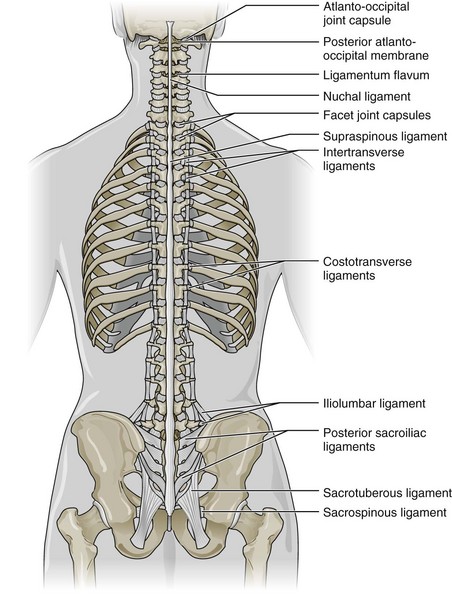

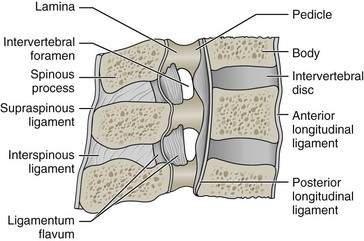

Prolotherapy injections are often administered with a fairly large 2.5- to 3-inch, 20 gauge spinal needle. This size of needle is preferred in order to deliver a bolus of somewhat viscous solution into targeted deep anatomic structures. The following areas are commonly injected for CLBP: posterior SI ligaments, iliolumbar ligaments, interspinous ligaments, supraspinous ligaments, and posterior intervertebral facet capsules (Figures 25-1 through 25-3). Some practitioners target ligaments that are tender to manual palpation or otherwise suspected of causing pain, whereas others prefer to inject all of the larger posterior ligaments that are easily accessible by injection and potentially associated with CLBP.5,10

Figure 25-1 Lumbosacral ligaments targeted with prolotherapy injections: anterior view.

(Modified from Muscolino JE. The muscle and bone palpation manual with trigger points, referral patterns, and stretching. St. Louis, 2009, Mosby.)

Figure 25-2 Lumbosacral ligaments targeted with prolotherapy injections: posterior view.

(Modified from Muscolino JE. The muscle and bone palpation manual with trigger points, referral patterns, and stretching. St. Louis, 2009, Mosby.)

Figure 25-3 Lumbosacral ligament targeted with prolotherapy injections: lateral view.

(Modified from Muscolino JE. Kinesiology: the skeletal system and muscle function, ed. 2. St. Louis, 2011, Mosby.)

To access these ligaments, the needle is typically inserted in the midline directly above an intervertebral space and oriented laterally to avoid accidentally injecting into the spinal canal (Figure 25-4). The needle is then inserted until the tip contacts bone and the plunger is partially withdrawn to confirm the absence of blood in the aspirate that would indicate possible blood vessel puncture. The desired bolus of solution, typically 0.5 to 2.0 mL, is then injected at each site.6 Practitioners often target several ligaments from a single needle insertion point by reorienting the needle in situ. The total amount of solution injected during one session of prolotherapy depends on the number of structures that are targeted and the bolus delivered to each structure; 10 to 30 mL is common. Radiologic guidance (e.g., fluoroscopy) is seldom used in prolotherapy.

Figure 25-4 Prolotherapy injection technique requires careful needle placement.

(© iStockphoto.com / Juanmonino.)

After the injection procedure, the patient is briefly observed and then sent home with instructions to perform repetitive spinal range of motion (ROM) exercises, such as standing lumbar flexion and extension to maintain flexibility if the acute inflammation produced by the injections results in lumbosacral stiffness and soreness over the next few days. Patients are also advised to use over-the-counter (e.g., acetaminophen) or prescription (e.g., hydrocodone) analgesics as needed to control pain in the few days after the injections. Instructions are also instructed to avoid anti-inflammatory medication, because the acute inflammatory reaction provoked by this treatment is considered beneficial.10

Theory

Mechanism of Action

As with many other treatments available for CLBP, the mechanism of action for prolotherapy is not well understood. This treatment was derived from sclerotherapy for varicose veins, where injected irritants provoke a localized acute inflammatory reaction, connective tissue proliferation, and lumen closure. In prolotherapy, four types of solutions have been identified according to their suspected mechanism of action: (1) osmotic (e.g., hypertonic dextrose); (2) irritant/hapten (e.g., phenol); (3) particulate (e.g., pumice flour); and (4) chemotactic (e.g., sodium morrhuate).17 Osmotics are thought to dehydrate cells, leading to cell lysis and release of cellular fragments, which attracts granulocytes and macrophages; dextrose may also cause direct glycosylation of cellular proteins.17 Irritants possess phenolic hydroxyl groups that are believed to alkylate surface proteins, which renders them antigenic or damages them directly, attracting granulocytes and macrophages.17 Particulates are also believed to attract macrophages, leading to phagocytosis.17 Chemotactics are structurally related to inflammatory mediators such as prostaglandins, leukotrienes, and thromboxanes, and are believed to undergo conversion to these compounds.17

Other mechanisms of action for prolotherapy that do not involve localized acute inflammation have also been proposed. For instance, macrophages that respond to particulates are believed to secrete polypeptide growth factor, leading to fibroplasia.17 Other hypotheses include neurolysis of nociceptive fibers (denervation) associated with phenol, lysis of connective tissue adhesions because of the large volume of solution injected, and neovasculogenesis or neoneurogenesis during the inflammatory cascade.18 A number of studies have been conducted in animals to elucidate the mechanism of action for solutions used in prolotherapy, including rat, guinea pig, and rabbit models.2 In general, these studies involved ligament or tendon injections and histological or biomechanical examination of connective tissue.

For example, rabbit medial collateral ligament mass, thickness, and weight-to-length ratio increased significantly 7 weeks after 5% sodium morrhuate injections.19 However, there were no differences in traumatized rat Achilles tendon tensile strength 7 weeks after injection of various solutions used in prolotherapy (e.g., dextrose, sodium morrhuate).20 Other studies reported changes consistent with local acute inflammation.2 In three patients with CLBP of suspected ligamentous origin, biopsies of posterior SI ligaments were taken 3 months after six weekly injections with dextrose 12.5%, glycerin 12.5%, phenol 1.25%, lidocaine 0.25%, SMT, and repeated trunk flexion exercises.21 Electron microscopy revealed a significant increase in cellularity and active fibroblasts, with a 60% increase in average fiber diameter.21