Chapter 8 Problems in older people

Introduction

Medical emergencies are common in older people and they may have difficulty accessing suitable health care once their GP practice is closed. They are less likely to use schemes such as NHS Direct than other parts of the population.1 They or their carers are more likely to dial 999 if they have an urgent medical problem. The care of the elderly is an increasing proportion of work for GP out-of-hours services, ambulance services and Emergency Departments.

Community systems for the care of older people

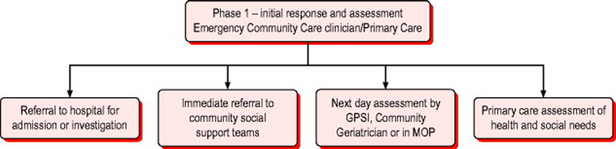

Figure 8.1 sets out the range of outcomes from community emergency assessment and shows the ideal system to respond to these emergencies. The community emergency medicine clinician carries out initial crisis support and a brief needs assessment. In significant numbers of older patients this will need to be backed up by either hospital or community services. The keys to success in such a system are excellent communication, mutual respect and clear referral pathways with common documentation systems.

Primary survey positive patients

The criteria for recognition of immediately life threatening problems are the same as for younger patients (Box 8.1). However the interpretation of vital signs may be more difficult and abnormalities need to be taken in context of pre-existing morbidity. A history from a reliable witness is essential. Previous neurological problems can make the GCS permanently <12. Similarly, the elderly are more prone to excessive bradycardia from cardiac medication but on the other hand, symptomatic heart block is common. Oxygen saturations should be interpreted in light of the known medical history and clinical setting.

Primary survey positive patients should be transferred as soon as possible by paramedic ambulance to an A&E Department or an Emergency Admissions Unit depending on local protocols. The exception might be those patients with documented ‘end of life decisions’ such as Advanced Directives and clear, agreed treatment plans which might include ‘do not attempt resuscitation’ (DNAR) orders.

Primary survey negative patients

In the elderly patient a greater emphasis must be given to factors other than the ‘medical problem’ alone. The variables to be considered are given in Box 8.2.