KEY POINTS

Therapeutic intervention in the multiply injured patient must be prioritized to maximize survival.

The degree of life threat posed by the alteration in physiology from each injury determines the order of priority.

Immediate priority is given to airway control and to maintenance of ventilation, oxygenation, and perfusion.

Cervical spine protection is crucial during airway assessment and manipulation.

When several personnel are involved, a trauma team leader is important to coordinate management in the multiply injured patient.

Safe effective techniques for airway control, chest decompression, and the establishment of intravenous access are key skills in management of multiple trauma.

After immediately life-threatening abnormalities have been corrected, systematic anatomic assessment is required to identify and manage other injuries.

Repeated assessment is necessary to identify changes in the patient’s status and institute appropriate treatment.

Although the institution of trauma systems has altered the pattern of mortality distribution following multiple injuries,1 it is still useful to consider the trimodal distribution pattern.2,3 The first peak of this trimodal distribution represents deaths occurring at the scene and results from such injuries as cardiac rupture or disruption of the major intrathoracic vessels, and severe brain injury that is incompatible with survival. Death from such injuries occurs within minutes of the traumatic event and medical intervention is usually futile. The second peak in mortality following multiple injuries occurs minutes to a few hours after the event. Mortality during this phase is related to injuries that are immediately life-threatening, such as airway compromise, tension pneumothorax, and cardiac tamponade. However, simple appropriate resuscitative measures can significantly affect the outcome during this phase. The third peak occurs as a result of complications of the injury, such as sepsis or multiorgan failure.3 However, mortality in this third phase can also be significantly altered by the type of intervention during the second phase. The intensivist dealing with the multiple trauma patient is very likely to be involved in the institution of resuscitative measures during the second phase as well as the management during the third phase of the complications of the injury or complications arising from inadequate treatment. Many of the chapters in this text deal with the complications of trauma, such as sepsis and multiple organ failure. This chapter will emphasize treatment priorities during the second peak of the trimodal distribution of trauma-related mortality.

Blunt trauma from motor vehicle collision is the most frequent cause of injuries in general. This type of impact usually results in injuries to many different parts of the body simultaneously. Such a patient may present with head and neck injuries as well as abdominal and extremity injuries.

When faced with multisystem injury, the intensivist must prioritize treatment according to the threat to the patient’s survival.4 Prioritization of assessment and intervention requires a coordinated team approach. Where personnel are available from different specialties, it is of paramount importance that the entire resuscitative effort be coordinated through an identified team leader. This very simple decision should be made prior to institution of therapy and can be critical to the outcome in the patient with multisystem trauma. The team leader, who may be an intensivist, must be completely familiar with a wide variety of injuries and the relative threat they pose to life in order to prioritize intervention and direct personnel appropriately.

The description of the order of priorities follows a sequence based on one primary physician conducting the entire resuscitation. However, as frequently happens in most trauma centers, when many physicians and paramedical personnel are available, assessment and management of several abnormalities occur simultaneously. For example, while the airway is being assessed and managed, intravenous access could be established by different personnel.

Certain fundamental concepts underlie the approach to resuscitation of the multiply injured patient. The most important of these is that immediately life-threatening abnormalities should be treated as they are identified. Therefore, assessment and resuscitation must proceed simultaneously. The initial goal in managing the trauma patient is to provide adequate oxygenation and perfusion. This goal is achieved by approaching assessment and treatment so that abnormalities in the injured patient that affect oxygenation and perfusion take top priority. It is not essential to establish a definitive diagnosis of the cause of the decreased perfusion or hypoxemia. For instance, airway obstruction may occur as a result of a head injury, hypoperfusion from hemorrhagic shock or secretions in the airway. In the initial resuscitative phase, airway compromise is treated in the same fashion regardless of what specific injury leads to this airway compromise. It is also of prime importance to recognize findings that suggest a need for emergent lifesaving surgical intervention so that appropriate personnel could be alerted as early as possible.

PRIORITIES

The order of priorities is a key feature for successful management of the multiply injured patient and should adhere to the following sequence:

Identification and correction of airway compromise and maintenance of oxygenation and ventilation with cervical spine precaution.

Identification and control of hemorrhage.

Identification and correction of other sources of inadequate tissue perfusion.

Identification and correction of neurologic abnormalities and prevention of secondary brain injury.

Total exposure of the patient to allow complete assessment while preventing hypothermia by minimizing the duration of this exposure.

Temporary stabilization of fractures.

Detailed systematic anatomic assessment and provision of definitive care.

In the Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) course for physicians,5 steps 1 to 5 constitute the Primary Survey, during which immediately life-threatening abnormalities are identified by adhering to the sequence ABCDE, where A stands for airway, B for breathing, C for circulation and hemorrhage control, D for neurologic disability, and E for exposure.

The basis for this order of priorities is the degree to which abnormalities in the different systems threaten the life of the patient. Adherence to this order allows assessment and resuscitation to occur simultaneously, because abnormalities will be identified in the order in which they are likely to threaten the patient’s life. Although the patient with multiple fractures requires treatment of these fractures, apart from hemorrhage control associated with the fractures, such treatment should take lower priority compared to treatment of abnormalities affecting the airway or respiratory status.

Complete evaluation requires assessment of the entire front and back of the patient, necessitating full exposure. Once this assessment is completed, the patient should again be covered to minimize heat loss and the risk of hypothermia.

The most frequent cause of airway obstruction in the multiply injured patient is loss of tone of the muscles supporting the tongue, either because of hypoperfusion of the brain from hypovolemic shock or because of central nervous system (CNS) injury. The simple maneuvers of chin lift and jaw thrust move the mandible forward. Because the tongue muscles are attached to the mandible, these actions move the tongue anteriorly and open the upper airway. It is essential in the trauma victim to inspect the oropharynx to ensure that there is no foreign material (including vomitus) in the pharynx that will occlude the airway. Quick observation of the patient’s nares and mouth and listening for unobstructed passage of air through the upper airway, together with inspection for the presence of foreign objects in the oropharynx, are all very simple maneuvers that should be undertaken in the initial care of the multiply injured patient. The patient who is fully conscious, vocalizing, and breathing adequately, and who is not in shock does not require an artificial airway.

The underlying principle of establishing an airway in the trauma victim is to institute the simplest technique that allows effective oxygenation and ventilation. Over 90% of patients do not require endotracheal intubation. Measures short of endotracheal intubation include the insertion of oropharyngeal or nasopharyngeal tubes, if these can be tolerated without stimulating gagging or vomiting. However, when endotracheal intubation is necessary, it should be performed promptly and expeditiously. Prolonged unsuccessful attempts at endotracheal intubation without oxygenation and ventilation should be avoided. Mask ventilation with oxygen and an oropharyngeal airway should be performed intermittently to avoid hypoxia during prolonged attempts at endotracheal intubation. All multiply injured patients should have oxygen administered by the most appropriate means as early as possible. A pulse oximeter should be attached to monitor O2 saturation, which should be maintained at 95% or greater. A definitive airway, defined as a cuffed tube securely placed in the trachea, is required if the patient is unable to maintain patency of the airway.

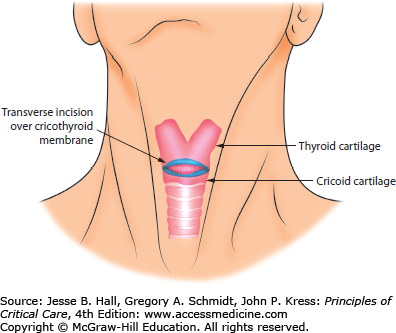

In very rare circumstances, the patient’s airway may not be patent and it may be impossible to establish an airway nasally or orally. In such situations, cricothyroidotomy is required. This procedure should only be done when an airway cannot be established by other, nonsurgical means.6 The landmarks for the cricothyroid membrane are indicated in Figure 117-1. A cricothyroidotomy may be done using a large-bore needle (needle cricothyroidotomy) or scalpel (surgical cricothyroidotomy), the former method being preferable in children under 8 years of age because the cricoid cartilage is essential to the stability of the upper airway of infants and young children. A 14-gauge needle and cannula may be inserted through the cricothyroid membrane and combined with jet insufflation for temporary oxygenation and ventilation. To maximize oxygenation and avoid hypercapnia, the needle cricothyroidotomy should be followed by tracheostomy in an operating room under ideal circumstances if a surgical airway is still required. The placement of the cricothyroidotomy needle allows approximately 30 to 45 minutes of adequate oxygenation and ventilation without severe hypercapnia. The surgical cricothyroidotomy is preferable and more effective in adults. A skin incision is made directly over the cricothyroid membrane, and after the subcutaneous structures are reflected, the cricothyroid membrane is identified and incised transversely. A pair of forceps is then inserted to spread the opening, and a tube of appropriate caliber, usually a 6F or 7F tracheostomy or endotracheal tube, is inserted through the opening and secured.

Many techniques for establishing an artificial airway are associated with risks of cervical spine injury. Awareness of these risks during airway intubation is crucial in preventing spinal cord injury in the multiply injured patient. Inappropriate manipulation of the cervical spine during airway intubation could convert an unstable cervical spine injury without neurologic deficit into one with permanent neurologic deficits, including paraplegia, quadriplegia, and even death. In a patient who is unconscious or who is suspected of having a cervical spine injury, the neck should not be flexed, extended, or rotated. In-line immobilization with the neck in the neutral position should be maintained while the airway is secured. Although the orotracheal route is more commonly practiced, if the patient is conscious and breathing, then a blind nasotracheal intubation may be attempted with cricoid pressure anteriorly. If the patient is apneic, then orotracheal intubation with in-line cervical immobilization will have to be attempted. Failure or inability to secure the airway by nonsurgical means in a patient who requires a definitive airway necessitates cricothyroidotomy. Where fiberoptic bronchoscopy or the gum elastic bougie is immediately available, it may be used to facilitate endotracheal intubation.7,8 During the initial process of resuscitation spinal protection is the main goal as opposed to spine imaging to diagnose a specific injury. All unconscious patients or patients suspected of cervical spine injury should have cervical spine imaging and all seven cervical vertebrae and the superior aspect of the first thoracic vertebra should be clearly visualized.9,10 This is usually conducted after the patient has been resuscitated and in many centers CT scan imaging is used rather than plain x-ray. If plain x-rays are used then, failure to visualize all seven cervical vertebrae and the top of the first thoracic vertebrae should necessitate other views of the spine, including a swimmer’s view. An open-mouth anteroposterior odontoid and anteroposterior x-ray view of the cervical spine should also be done. If there is doubt as to the presence of a cervical spine injury, the neck should be immobilized with a semirigid cervical collar and computed tomography (CT) is performed to assess the integrity of the cervical spine. If the patient is awake and alert and has no cervical pain or tenderness or other abnormality on physical examination, then the cervical collar may be removed after adequate cervical spine x-rays. In the presence of clinical signs of spinal cord injury, the cervical spine is considered to be abnormal even if the cervical spine imaging appears normal. In selected patients who have not had a period of unconsciousness or another painful distracting injury, and are alert and have no clinical evidence of cervical spine injury, imaging of the cervical spine may be omitted and the cervical collar removed.11

Adequacy of ventilation is quickly assessed by observation of the chest for asymmetrical or paradoxical movement, followed by quick auscultation and percussion to determine whether there is any hyperresonance or dullness to suggest pneumothorax or hemothorax. Deviation of the trachea suggests the presence of a pneumothorax or hemothorax, but this finding is not always evident. Although one may confirm the diagnosis of a simple traumatic pneumothorax with an upright chest x-ray, suspicion of a tension pneumothorax requires immediate decompression, without prior x-ray confirmation. Further examination of the chest should be conducted to determine the presence of other life-threatening thoracic injuries, such as cardiac tamponade, open pneumothorax, flail chest, ruptured thoracic aorta, and massive hemothorax (see Chap. 120).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree