Introduction

Achieving quality in health care requires a focus on continuous performance improvement. Physicians pride themselves on being subject matter experts in their focused area of medical practice. Although such knowledge is critical for developing changes that result in improvement, alone it is not sufficient to produce fundamental changes in the delivery of health care. Physicians who practice in complex hospital and health care systems must acquire another kind of knowledge in order to develop and execute change.

W. Edwards Deming, an American statistician and professor who is widely credited with improvement in manufacturing in the United States and Japan, has described this knowledge as a “system of profound knowledge” Figure 14-1. This knowledge is composed of the following items: appreciation for a system, understanding variation, building knowledge, and the human side of change. These concepts are not taught in many medical school, yet are essential for physicians and other healthcare providers who are passionate about improving the systems around them.

All hospitalists have witnessed changes that did not result in fundamental improvements within their hospital systems: the computerized order set that was successfully implemented but never revised based on prescribers’ feedback, the paper checklist for medication reconciliation that never gets filled out, or the new rounding system that worked for the first few weeks but then failed to become a standard part of practice due to physician variation or lack of commitment. These are all examples of first-order changes—changes that only returned the system to the normal level of performance. In quality improvement work, individuals must strive for second-order changes, which are changes that truly alter the system and result in a higher level of system performance. Such changes impact how work is done, produce visible, positive differences in results relative to historical norms, and have a lasting impact. Although the model for improvement described below may seem simple, it is actually quite demanding when used properly; and the process is essential to both learning and ultimately changing complex systems.

|

Plan-Do-Study-Act as a Tool for Quality Improvement

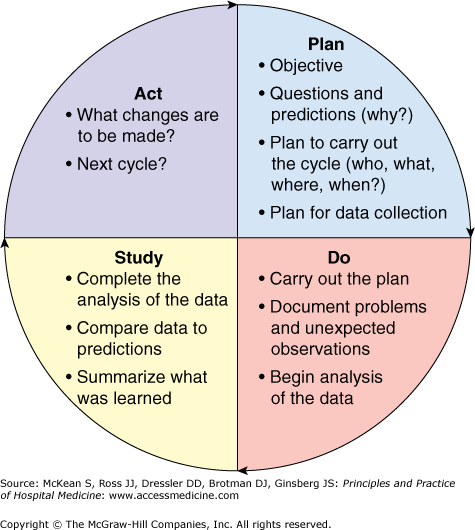

The Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) model is a commonly used tool in quality improvement (QI) science. Shewart and Deming described the model many years ago when they studied quality in other industries. This model first appeared in health care when Berwick described how the tools could be applied and emphasized an iterative approach to change. Using a “trial-and-learning approach” in which a hypothesis is tested, retested, and refined, the PDSA cycle allows for controlled change experiments on a small before expansion to a larger system. The four repetitive steps of PDSA—plan, do, study, and act—are carried out until fundamental improvement, which can be exponentially larger than the original hypothesis, takes place Figure 14-2

|

During the Plan phase, the team generates broad questions, hypotheses, and a data collection plan. It is critically important during this period to define expectations and assign tasks and accountability to every team member. In the planning phase of the PDSA cycle, it is prudent to invest significant time and develop a well-framed question by reviewing related research and local projects and defining meaningful process and outcome measurements. Broad questions at the outset of a PDSA cycle can include “What are we trying to accomplish?” and “What changes can we make that will result in an improvement?” The ideal data collection tool answers the question: “How will we know that a change is an improvement?” It is also helpful for the team to generate predictions of the answers to questions early on. This aids in framing the plan more completely, to uncover underlying assumptions or biases before any testing, and to enhance learning in the Study phase by providing a baseline point of comparison.

Teams new to QI frequently will struggle with the question, “How do we measurement?” Defining discrete process measures is a good starting point when using PDSA. Process measures are used to assess whether the cycle is being carried out as planned. This is in contrast to outcome measures which are used to track success or failure and focus on the specific outcome that the team is trying to achieve (see Chapter 15).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree