CHAPTER 4

Primary Care in the Community: Assessment and Use of Resources

Stephen Paul Holzemer, PhD, RN • Joanne K. Singleton, PhD, RN, FNP-BC, FNAP, FNYAM • Carol Green-Hernandez, PhD, ARNP, FNP-BC, FNS

STRATEGIC USE OF RESOURCES

STRATEGIC USE OF RESOURCES

One key aspect of integrated systems in primary care is the use of community assessment to guide the strategic use of resources. Participation in proactive primary care requires that providers know the actual and potential health-related problems in the community and know how to secure the resources to ameliorate them. Chapter 1 provided a context for examining the uncertainty of how systems of care will adapt to changes in the contemporary health care marketplace. This chapter promotes the importance of studying the community and its resources to meet the needs of people in changing care delivery systems.

Primary care providers from all disciplines are challenged to work together with their patients to create comprehensive primary care networks. Accurate and complete community assessment ensures that the picture of available health care resources is clear to both patients and providers. Evidence of a caring relationship between providers and patients can promote the public’s confidence that resource allocation decisions have the potential to promote the primary care needs of patients, families, and communities (deChesnay & Anderson, 2008; Gorski, 2000).

The meaning of relationship-centered care for the community as a whole is reviewed, and examples of aggregate-level interventions are identified and discussed in this chapter. The Alliance for Health Model is introduced as one model that could be helpful for providers to use when participating in community assessment—a critical process in obtaining appropriate resources for relationship-centered primary care delivery (Holzemer, 2014). The often-preferred term patient-centered care is used in this chapter with the understanding that the relationship sought by the primary care provider is often beyond the individual patient, including the family and community as well.

PATIENT (RELATIONSHIP)-CENTERED CARE IN THE COMMUNITY

PATIENT (RELATIONSHIP)-CENTERED CARE IN THE COMMUNITY

Primary care providers and patients are responsible for creating acceptable plans of primary care. These plans are a reflection of professional caring, which frames patient-centered care. Patient-centered care respects and promotes the work of both the patient and the provider to improve health (Public Health Leadership Society, 2002; Thomas, 2004). These relationships are displayed at the community level in the form of aggregate data, or health indicators on a population level (Truglio-Londrigan, Singleton, Lewenson, & Lopez, 2013).

Aggregate health indicators include variables such as morbidity, mortality, clean air standards, statistics on civil disobedience and unrest, family and community violence rates, and patterns of providing primary care to groups of people who cannot pay for care. Each community will have similar and different health indicators that reflect an aggregate level of wellness. Healthy communities are those where people, families, groups, and larger aggregates can work in harmony to create the primary care systems (with providers) that meet the needs of the public (Hickey & Brosnan, 2012; Singleton & McLeod-Sordjan, 2013).

Primary care occurs within the relationship that develops between a health care provider or health care team and a patient, family, group, or community (the care recipient). The outcomes of these relationships are intended to heal or move the patient (and the community as a whole) toward improved health. The definition of healing or health differs according to patients’ cultural or ethnic and spiritual beliefs as well as their experience in getting their health care needs met. The overall success that people, families, and groups have in meeting their health needs as a whole provides a picture of the health of a community.

Patient-centered care respects the needs of patients and is within the legal and ethical mores of society. Providers use standards of care if the patient cannot make his or her ethical and legal wishes for care known. The following two situations examine the relationships between patients and providers. The relationships are examples of interactions on a one-to-one level. To reiterate, the overall sum of relationships between providers and patients is one way to illustrate a community’s health. Community assessment, discussed later in this chapter, is a strategy to monitor the health of the relationships between the aggregate of patients and care providers.

In Situation 1, the primary care provider is working with a patient who does not want to continue conventional treatment for her illness. The interaction between this provider and the patient can have an impact on the community. Allowing patients as a group to control decision making about care could be the first step in, for instance, negotiating hospice services for a growing elderly population, creating legislation to expand home care benefits for patients at the end of life, and changing the curricula in primary care programs to emphasize patient self-determination.

In Situation 2, the patient continues to inject drugs and does not follow the health care goals set by him and the provider. The patient participates only sporadically in health care services, failing to establish a sound relationship with the provider because of his addictive behavior. Primary care providers are responsible for maintaining some level of a relationship even when the patient is not participating in his or her care. A population-focused intervention that could develop from a situation where provider–patient relationships are not working could include implementing a street-based mobile health care service, increasing the cadre of drug addiction counselors to provide more support to the drug-addicted population, and developing a system of recreation activities to discourage drug use in neighborhoods where prevalence is high.

SITUATION I: MS. DAREN IS READY TO DIE

SITUATION I: MS. DAREN IS READY TO DIE

Ms. Daren is a 65-year-old widow who is ready to die. Her primary care provider is optimistic that Ms. Daren will want to enjoy life more once her chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is better controlled by medication. Ms. Daren refuses to enter the hospital and wishes to be maintained at home on low-dose oxygen therapy alone. Ms. Daren has a living will that reflects her wishes.

Evidence of Patient-Centered Care

The primary care provider in this situation has a challenge to make sure that Ms. Daren is competent to make decisions about her care. The primary care provider should assess Ms. Daren for confusion, depression, or a neurological deficit that could impair judgment, review medication combinations that could affect pain relief or ease of respirations, and verify Ms. Daren’s decision with family members to elicit their support. The primary care provider then sets up home care services that will support the decision of Ms. Daren to stay at home and makes a referral for hospice services as needed.

These situations reflect the dynamic relationships between patients and their care providers. Patient–provider relationships extend to the community as a whole as primary care providers implement population-focused activities to improve the health of the public. Primary care providers should participate in creating a plan, in partnership with the public, that outlines how to allocate resources that will maintain the health of the community (Association of State and Territorial Health Officials, 2013; Holzemer & Belcher, 2014; Thomas, 2004). A community may need more health-related teaching about issues important to the community. Resources might be needed, for example, to screen for or treat an emerging communicable disease.

SITUATION 2: MR. WHITE CHOOSES TO KEEP INJECTING DRUGS

SITUATION 2: MR. WHITE CHOOSES TO KEEP INJECTING DRUGS

Mr. White is under the care of a primary care provider to monitor his diabetes and methadone maintenance. He is thought to be an active injection-drug user and is not following diabetic dietary guidelines even though he has access to government food coupons.

Evidence of Patient-Centered Care

The primary care provider facilitates getting Mr. White placed in drug rehabilitation. After many meetings with the interprofessional team, the primary care provider is unsuccessful in helping him participate more fully in his health care; Mr. White rejects drug rehabilitation. The primary care providers make every effort to invite Mr. White back into a more full therapeutic relationship, when he continues to come to the primary care clinic for episodic, sporadic care. The primary care staff members assisted the patient’s closest friends and relatives in coping with Mr. White’s decision to not enter a recovery program. They are referred to social services and psychological counseling to assist them in coping with the patient’s decision.

ROLE OF COMMUNITY ASSESSMENT IN PRIMARY CARE

ROLE OF COMMUNITY ASSESSMENT IN PRIMARY CARE

The relationships of primary care providers and patients on the whole can be examined through community assessment. The results of the community assessment, a picture of the community’s health, can be used to allocate resources to improve the health of the community. The Alliance for Health Model provides one blueprint to help students and primary care providers understand components of community health assessment and care delivery. This model offers a view of health and illness that incorporates the health care needs of the community as well as the process of obtaining sufficient resources to support systems of care delivery.

The Alliance for Health Model identifies the relationship between the provider and the care recipient as critical to successful care delivery. Over time, providers and patients develop relationships that allow for sound, cost-effective decision making when these relationships foster cooperation. Primary care providers may not actually conduct a community assessment, but need to be aware of the data that are collected, and may be of critical importance to them as they plan and develop care strategies. Providers depend on community assessment data provided by state, territorial health departments, the census, and regional assessment projects (National Center for Health Statistics, 2011–2013).

Components of the Alliance for Health Model

The five components of the model represent core areas for assessment:

Community-based needs

Community-based needs

Care-management techniques

Care-management techniques

Influences on resource allocation decisions

Influences on resource allocation decisions

Expertise of the interprofessional team

Expertise of the interprofessional team

Validation of services by the patient

Validation of services by the patient

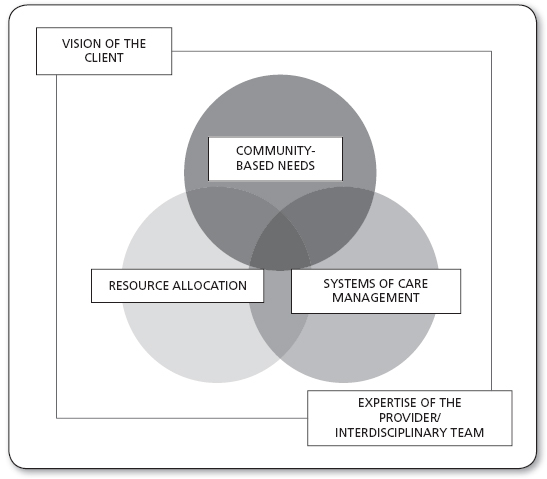

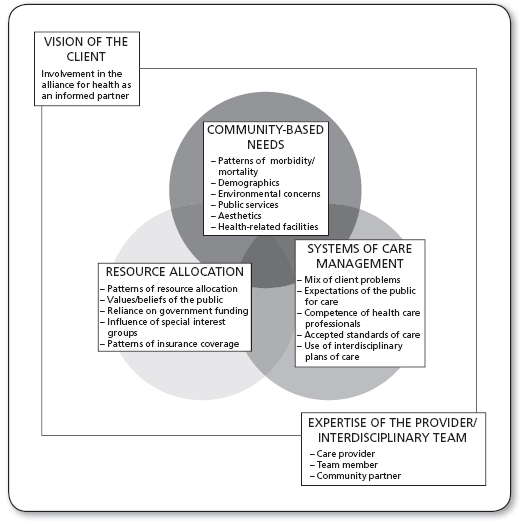

The Alliance for Health Model, shown in Figure 4.1, helps providers to view health concerns beyond a narrow, one-discipline perspective. Each of the five components of the model is considered essential for working in the community and making proper clinical judgments about the care that patients need. The first three components represent the core of patient concerns. The last two components stress the important components of provider and patient involvement in the process. Primary care providers play a role in assessing each of the five essential components, although different providers will have special skills in one or more areas. Figure 4.2 represents these roles as they relate to the care of patients in primary care.

COMMUNITY-BASED NEEDS

Community-based needs include but are not restricted to the assessment and analysis of the sources of information found in Table 4.1. Needs are identified by formal study of the community in a community assessment, as well as through the long-term relationship developed between professionals and the public. The way community-based needs are met or not met is a reflection of how professionals and the public manage care and allocate resources. Because each community has unique health care needs, primary care providers must reevaluate their assessment of community needs frequently.

FIGURE 4.1

The Alliance for Health Model for community health assessment and care delivery.

Source: From Holzemer (2014).

CARE-MANAGEMENT TECHNIQUES

The management of health care is a complex phenomenon and includes the variables listed in Table 4.1. Care-management techniques develop and change according to the evolution of health care problems (community-based needs) and decisions about how populations allocate resources. Various communities may manage care differently; primary care providers need to be flexible about how they approach care-management issues.

INFLUENCES ON RESOURCE ALLOCATION DECISIONS

A number of variables influence resource allocation decision making; some of these variables are listed in Table 4.1. In any community, one or more of these variables may influence resource allocation decisions at the same time. The major influences on how health care resources are allocated are associated with care-management techniques and the volume and complexity of community-based needs.

When the resources to provide care are limited, rationing of high-technology care is required to provide a more comprehensive level of care. Care providers and recipients need to discuss how limited resources should be allocated in an ethical way. Without a guarantee of services (i.e., national health plan) and with the free market, a two- or multiple-tiered system of health care will exist: People with financial means will have one level of care, and the poor will have another.

Primary care providers are partly responsible for the resources they allocate to provide care. Variables such as budget restrictions, the mission of organizations, and the preferences of more traditional gatekeepers (i.e., administrators, physicians) all affect the resource allocation decisions of primary care providers. However, the influences on resource allocation do not absolve primary care providers from the responsibility of providing resources to their patients appropriately. When systems allocate resources unfairly, providers have the responsibility to work to correct these systems.

The way patients are referred in the use of community resources is critical. Providers need to make sure that referring the patient to community resources is not a negative experience that could adversely affect primary care. Providers should not refer patients to resources that have not been validated as appropriate from financial, cultural, and functional perspectives. It is the responsibility of providers to evaluate the community resources being used by their patients.

Details of Variables in the Categories of Community-Based Needs, Care-Management Techniques, and Influences on Resource Allocation Decisions |

COMMUNITY-BASED NEEDS |

Patterns of morbidity and mortality Demographics (age, gender, education level, income, housing) Environmental concerns Public services (fire, police, sanitation, education, recreation, sports) Aesthetics (art, music, culture, religion) Health-related facilities (hospitals, community-based organizations, faith-based communities, subacute and custodial facilities, public health facilities, home care organizations) |

CARE-MANAGEMENT TECHNIQUES |

Mix of patient problems Expectations of the public for care Competence of professionals Accepted standards of care Use of interprofessional care plans or action plans |

INFLUENCES ON RESOURCE ALLOCATION DECISIONS |

Patterns of resource allocation Values and beliefs of the population Reliance on local, regional, and federal government funding Influence of special-interest groups on resource allocation decisions Patterns of insurance coverage |

EXPERTISE OF THE INTERPROFESSIONAL TEAM

The expertise of the interprofessional team depends on the involvement of all disciplines giving care. Although each team member will be somewhere on the continuum between expert and novice, the team as a whole needs to be competent to care for the public’s health. With varied expertise, the team will have the resources to make referrals within and outside the group. Team members need to work together successfully to make a positive difference in the care people receive.

VALIDATION OF SERVICES BY THE PATIENT

Health care services must be available, accessible, affordable, appropriate, adequate, and acceptable (Krout, 1994). Only patients can validate health-related services as being those that they want or need. Certain vulnerable populations, such as prisoners, children, and people with severe disabilities, need to have others act for them to validate services. If it is impossible to validate services with the patient or his or her health care proxy, the provider should offer services that reflect a general standard of care. Standards are generated by professionals who are charged with defining safe and prudent care. The standard of care must reflect regional or national research-based best practices.

THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN THE ALLIANCE FOR HEALTH MODEL AND EVIDENCE-BASED CARE

THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN THE ALLIANCE FOR HEALTH MODEL AND EVIDENCE-BASED CARE

The Alliance for Health Model is closely related to the essential components of evidence-based care in three ways. First, the core of community-based needs—systems of care management—influences resource allocation decisions and should be grounded in the appropriate qualitative or quantitative research findings. For example, research information on the spread of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), or the prevalence of multiple chronic conditions directly informs the core of safe and effective care (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2013; Ward & Schiller, 2013).

In addition to research, to inform the core of safe and effective care, the Alliance for Health Model requires that the expertise of the interprofessional team and validation of services by the client are the two variables that place the health care event in proper context (Holzemer, 2014). It takes time for the elements of problem assessment, expertise of the provider, and needs of the client to come together. The movement of the “relationship” in patient-centered care to a mature exchange allows the provider and the patient to improve their efforts to move toward, and maintain, the highest level of health. The gold standard of research is complemented by the delivery of patient-centered care.

COMPARISON OF TWO COMMUNITIES

COMPARISON OF TWO COMMUNITIES

Table 4.2 uses the components of the Alliance for Health Model for community assessment to compare a fictitious inner-city community and a fictitious rural community. In this example, the inner-city community is made up of many city census tracts; the rural community has borders that represent large geographic areas. Each of the components of the assessment reflects aspects of health or illness of the two communities. The communities have very different problems that require different solutions.

The comparison of the inner-city community with the rural community reveals few similarities. The states of health, support networks, and use of resources are very different. The successful primary care provider approaches each community as a unique set of problems and potentials. Strategies of intervention may vary, but the focus on improving health by strengthening the relationships between providers and patients is central to working with both communities.

Population-focused interventions for the inner-city community could include:

Holding community discussion groups led by leaders of the houses of worship and lay caregivers

Holding community discussion groups led by leaders of the houses of worship and lay caregivers

VARIABLE | COMMUNITY A | COMMUNITY B |

Community-Based Needs | Inner-City Community | Rural Community |

Patterns of morbidity and mortality | The major causes of death and illness are HIV disease, violence, injection-drug use, and heart disease. Poor eating and exercise patterns are related to a sense of apathy and hopelessness in the community. Incidence of hypertension and high cholesterol levels are above state and national levels. | Major causes of illness and disability are cerebrovascular accident, cardiovascular problems, diabetes mellitus, and trauma from farm equipment and motor vehicle accidents. |

Demographics (age, gender, education level, income, housing) | One-fifth of residents do not live to the age of 25 years. One-third are high-school dropouts and 45% live in subsidized housing. The unemployment rate is 60%. | The majority of residents older than 70 years are women on fixed incomes. Residents younger than 65 years engage in farming and service-related occupations. Eight percent are college graduates; 67% completed high school. |

Environmental concerns | Twenty percent of the public housing does not meet inspection codes. The general community spaces are not considered safe after sunset. The last major business in the area was closed for improper waste disposal. | Farmhouses and in-town homes are clean but sparsely decorated. Fresh-water wells provide the majority of drinking water. Most residents plant gardens for food. Regulation of pesticides is limited. |

Public services (fire, police, sanitation, education, recreation, sports) | Emergency medical services (EMS) response time is twice that of the city as a whole. Government services are lacking in many areas and satisfaction with services is poor. An evening sports program for children younger than 16 years is very popular and includes door-to-door transportation. | Health-related services (i.e., ambulance, first aid) are provided by trained volunteers. Recreation and sports activities are primarily related to what is available on radio and television. The centralized school district covers a 30-mile area. |

Aesthetics (art, music, culture, religion) | The neighborhood houses of worship provide the primary aesthetic support and socialization of new residents into the community. | A city large enough to support a museum and music hall is 250 miles away. A movie theater provides some entertainment for the community. |

Health-related facilities (hospitals, community-based organizations, etc.) | The geographic area has one 450-bed city-run acute care facility and two public health clinics (sexually transmitted disease and maternal–child care). There are no elder-care or psychiatric facilities in the community. | A skilled nursing facility and an emergency center are located in the community. Acute/intensive hospital care is located 75 miles away. Limited home care is provided by the public health department. |

Systems of Care Management | ||

Mix of client problems | HIV and injection-drug use problems are twice the regional average. The community is considered the most dangerous in the category of violence to others. | Health problems are compounded among the under-or uninsured. Spousal abuse is thought to be 15% lower and depression 25% higher than that in larger communities. |

Expectations of the public for care | The community has a general feeling of apathy and hopelessness related to getting the care they need. Lay caregivers using herbal therapies provide some care in makeshift clinics. | Care expectations are restricted to the services that are available. Some people use fewer services because of long travel and the related loss of income. |

Competence of professionals | The majority of primary care providers have extensive experience. The acute care providers have a 33% turnover rate. Lay community workers have an extensive orientation and evaluation program. | Twenty percent of the providers in the skilled nursing facility have formal geriatric certification. Primary care providers are difficult to attract and retain because of geographic isolation. |

Accepted standards of care | The Joint Commission has placed the hospital on warning to lose accreditation because of unmet standards in obstetric care. The public health department has full accreditation from the Community Health Accreditation Program (CHAP). | The retirement facility is licensed by the state to operate. Complex care is usually not managed in the community; some members of the community are hesitant to report symptoms for this reason. |

Use of interprofessional care (or action) plans | The quality care management team of the municipal hospital system is implementing interprofessional care plans in all areas except HIV care and psychiatric care. Some providers feel that the care requirements in these areas are changing so rapidly that care guidelines are not useful for these patients. | The geographic space between providers limits the use of interprofessional plans of care. Referral from provider to provider is the standard of practice. |

Influences on Resource Allocation | ||

Patterns of resource allocation | The inner-city community relies on services that require city budget approval yearly. | The area’s residents are very conservative with resources. Residents have little influence on obtaining resources at the state level because of budgetary problems. |

Values and beliefs of the population | The community relies on the leaders of their houses of worship for direction. | People in the rural area are politically conservative. Traditional family structures are valued by the residents. |

Reliance on government funding | Funding for inner-city activities will soon be incorporated into block grants. Residents are suspicious about who will act as their advocates. | The community has basic needs covered by Medicare and Medicaid. |

Influence of special-interest groups on resource allocation | The inner city provides little special-interest concerns except for developers who want to displace residents for more business development. | Conservative religious groups live in the rural area. Many attempts have been made to influence the primary and secondary school curricula with religious beliefs. |

Patterns of insurance coverage | Sixty-six percent of residents are not insured. | The residents rely on Medicare and Medicaid to support their health-related needs. |

Expertise of the Interprofessional Team | ||

| Primary care providers in this community are expert providers, but the high turnover rate makes team cohesiveness problematic. | The community cannot support many specialists. The few primary care providers are well credentialed. |

Validation of Services by the Patient | ||

| As previously noted, the community (as patient) has little sustained interaction with primary care providers. | Town meetings to give health updates are well attended. Changes in service delivery are advertised in many local newspapers. |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree