Chapter 14 Prevention of Positioning Injuries

Positioning the surgical patient is a vital component of perioperative nursing practice and must be completed with knowledge and forethought. To safely and correctly position the surgical patient, the entire team must have a thorough understanding of the surgical procedure, the position desired, the physiologic effects of the position, time required in the position, and the anatomic boundaries. To prevent positioning injuries, the perioperative nurse must complete a preoperative assessment that includes such factors as the patient’s current health status and identification of comorbidities that will influence the course of the surgical procedure. Assessments should also include, but are not limited to, preexisting skin conditions, age, preexisting nerve conditions, nutritional status, physical/mobility issues, and height and weight (Association of periOperative Registered Nurses [AORN], 2009). Other safety factors such as the use of pressure redistributing surfaces and positioning devices must be considered in advance to safely position the surgical patient. Care should always be taken to have an adequate number of persons available to position and transfer the patient. Postoperative skin assessments should be performed as well. Assessments should include skin condition, areas of tenderness, and complaints of pain, numbness, or tingling in peripheral extremities.

The goals of patient positioning are (1) optimal exposure for the surgical team, (2) main-tenance of correct body alignment, (3) support of respiratory and cardiovascular function, (4) protection of neuromuscular function, (5) protection of skin integrity, and (6) to allow for anesthesia access (Heizenroth, 2007).

ADVERSE EVENTS

Despite more than three decades of research on iatrogenic events occurring in operating rooms (ORs) across the country, few identifiable or predictable causes of these injuries have been found (Gwande et al, 1999). Because of the lack of identification, there is a paucity of information regarding complications related to surgical positioning (Warner, 2009). Regardless of the cause, adverse events are expensive to the hospital and patient, may cause permanent disability, and are potentially deadly. Patient safety advocates and the public now hold health care providers and health care workers responsible for adverse events occurring in operating rooms across the United States. Nurses are being held accountable not only for nursing practice, but also for the identification of risk factors for adverse injury, preventive measures, and adherence to standards and recommended practices. Standards and recommended practices for positioning of the surgical patient are set forth by the Association of periOperative Registered Nurses (AORN). Positioning of the surgical patient requires several members of the perioperative team (i.e., surgeon, anesthesia provider, perioperative nurse, surgical technologist, and orderly) to participate in positioning the patient and ensuring implementation of appropriate positioning principles. Each member of the perioperative team must be knowledgeable and comply with the accepted AORN standards and recommended practices specific for proper positioning techniques and provide for the safety of the patient.

Pressure-Related Injuries

Anatomy and Physiology of the Skin

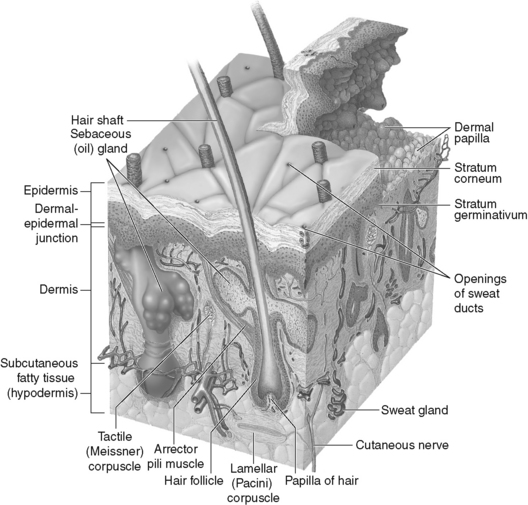

The skin is the largest organ of the human body and protects the internal body from injury, temperature changes, and bacterial invasions (Taylor et al, 2008). The skin also reduces water loss and acts as a permeable barrier to the environment (Boyce and Pittet, 2002). Human skin is made up of two layers, the epidermis (the outer layer) and the dermis (the second layer). The epidermis is generally only 0.1 to 1.5 mm thick (Patton and Thibodeau, 2010). It is made of stratified layers of epithelial cells and forms a waterproof top (Taylor et al, 2008). The epithelial layer is constantly shedding and regenerating each day. The five layers of epithelial cells include the basal cell layer, the squamous cell layer, the stratum granulosum, the stratum lucidum, and the stratum corneum. This layer also houses the hair follicles, sebaceous glands, and pilosebaceous glands (Heizenroth, 2007).

The dermis, or the second layer of skin, contains blood vessels, nerves, and lymphatic vessels (Patton and Thibodeau, 2010). It is also composed of three types of fibrous connective tissues: (1) collagen, (2) elastin and reticulin, and (3) a gel-like, ground substance. The dermis contains blood vessels, nerves, and lymphatic vessels (Figure 14-1). The dermis lies directly below the epidermis and is much thicker. Sweat glands and sensory nerve endings are in rich supply in the dermis. Two layers make up the dermis: the capillary layer and the reticular layer. Nerve endings and blood vessels lie within the reticular layer. Pressure within the dermal layer affects the nerve cell receptors, including receptors that sense pain, heat, cold, itch, and pressure. After injury, the dermal layer does not regenerate as the epidermis does; instead it forms granulation tissue.

Pressure Ulcers

Pressure ulcers are a major health problem affecting approximately 3 million adults (Ayello and Lyder, 2007). According to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) (Russo, 2008) hospitalizations involving patients with pressure ulcers increased by nearly 80% between 1993 and 2006. Pressure ulcers are defined by the National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (Black et al, 2007) as a localized injury to the skin and/or underlying tissue usually over a bony prominence as a result of pressure or pressure in combination with shear and/or friction. They are staged using the system in Box 14-1. The Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) has made the prevention of pressure ulcers 1 of 12 interventions in its 5 Million Lives Campaign (Ayello and Lyder, 2007).

BOX 14-1 Pressure Ulcer Definition and Stages

Copyright © NPUAP 2007. From National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel’s updated pressure ulcer staging system, Dermatol Nurs 19(4):347, 2007.

Millions of surgical procedures are performed each year. During the surgical procedure, patients are anesthetized and often put into positions that may cause pressure or compression to the tissue for long periods of time. Being unconscious and immobile, the patient cannot complain of pain or discomfort. Pressure ulcers develop when capillaries supplying the skin and subcutaneous tissues are compressed enough to slow down perfusion, causing aggregation of blood at the site of pressure, thus leading to ischemia to the area under pressure (Ayello and Lyder, 2007).

Development of pressure ulcers may result in increased patient pain, increased hospital stays, possible disfigurement, and increased cost for the institution. Estimates for treatment of a pressure ulcer can total as much as $100,000 to heal one full-thickness ulcer (Scott-Williams, 2006). Nationally the average cost to treat pressure ulcers is reported to be 2.5 times the cost of preventing them (Ayello and Lyder, 2007). In addition to the cost of treatment, development of a pressure ulcer can leave the institution open to potential litigation. More than 17,000 pressure ulcer–related lawsuits are filed every year, and the settlement involving health care–acquired pressure ulcers is usually about $250,000 (Scott-Williams, 2006).

Pressure ulcers in the OR usually result from improper positioning, inadequate padding and protection, incorrect use of positioning devices, or extended periods of pressure while on the OR bed (Fawcett, 2004). Pressure ulcers acquired in the OR are often mislabeled as burns or as an area of erythema because pressure ulcers acquired in the OR react differently than those acquired in the general hospital or extended care facilities. Operating room–acquired pressure ulcers do not usually present themselves until 3 to 5 days postoperatively and develop from the deep tissue, progressing to the outer surface. Pressure ulcers occurring from the operating room often deteriorate fairly rapidly to a stage III or stage IV (Blackett and Falconio-West, 2009). Following the surgical procedure, the perioperative nurse should assess the patient for areas of erythema or blanching on the skin. Particular attention should be paid to the heels, occiput, scapula, and coccyx because these are the most frequent sites for development of pressure ulcers in the OR.

Previous studies have demonstrated that the heels are the most common site for pressure ulcers and that 25% of these start during surgery (Box 14-2) (Huber and Huber, 2009). Furthermore, 83% of these develop during the first 5 days of hospitalization (Bansal et al, 2005; Huber and Huber, 2008). Many pressure ulcers can be prevented with an understanding of the etiology of pressure ulcers and principles of proper positioning, off-loading, and interface pressures. Off-loading is the process of removing or taking off pressure from a pressure point. The surgical team may completely off-load pressure by raising the heel or using heel devices that off-load. Interface pressure is a measurement of the interaction between the surface and the patient. Normal interface pressures are between 25 mm Hg and 32 mm Hg. It must be kept in mind that the interface pressure is a measurement of only one point in time and demonstrates where the pressures are the highest at that time. The incidence of heel pressure ulcers can be reduced or prevented by off-loading the pressure. Care must be taken so that devices used to off-load pressure do not increase the potential for deep vein thrombosis. Maintaining alignment, the correct use of devices, and use of surfaces that redistribute pressure promote patient safety.

Nerve Injury

An iatrogenic nerve injury caused by improper positioning for a surgical procedure, external compression, or twisting is another possible surgical complication (Dillavou et al, 1997). Although the true cause of peripheral nerve injury is unknown, it has been assumed that external pressure/compression against the nerve during the surgical procedure is the primary cause. In 1894 Budinger first recognized that there was a relationship between improper positioning and peripheral nerve injury. Stretching and compression are often identified as the main culprits in position-related nerve injuries (Heizenroth, 2007). Whatever the true cause of these events, it is a reminder to nurses that they must comply with guidelines and standards for safe positioning of the surgical patient.

Peripheral nerve injuries that occur during positioning may cause impaired function (Fawcett, 2004; Heizenroth, 2007). Nerve injuries are often broken down into upper extremity nerve injuries and lower extremity nerve injuries (Box 14-3).