Key Clinical Questions

What are the common preventable complications of intensive care unit (ICU) care?

What components are included within the care bundles to reduce catheter-related blood stream infections and ventilator-associated pneumonia?

What pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions may be used for prevention of venous thromboembolism in the ICU?

Which ICU patients are high risk for stress ulcer bleeding and require pharmacologic prophylaxis? When should prophylaxis be discontinued?

What are the essential elements of interdisciplinary care in the ICU?

Introduction

Critical illness places patients at high risk for various complications during hospitalization. Invasive monitoring devices, mechanical ventilatory support, immobility, and debility due to illness all contribute to susceptibility to these complications. Previously considered unavoidable consequences of critical illness, many ICU-related complications can be prevented.

In recent years, the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) and other national organizations have advocated the adoption of a series of “bundles” with the goal of reducing the rate of complications in the ICU. Bundles aggregate evidence-based practices relevant to a diagnosis or procedure into a single intervention. The rationale for the use of bundles is that, when their elements are reliably applied together, they allow more uniform application of best practices and, thus, improve patient outcomes. Bundles represent one of many tools needed to prevent ICU-related complications (Table 136-1).

| IHI Central Line Bundle* | IHI Ventilator Bundle† |

|---|---|

|

|

|

For each preventable ICU complication, this chapter will address epidemiology and strategies for prevention. Finally, daily goals of care will be addressed. Critical care practitioners can ensure the essential elements of preventive care in the ICU are implemented by incorporating a worksheet for daily goals of care.

Common Complications in the ICU

Catheter-related blood stream infections (CR-BSIs) cause significant morbidity and mortality in the ICU, and increased length of stay as well as cost. Primary blood stream infections are most often related to infected intravascular devices, mostly central venous catheters. At least 80,000 new cases of CR-BSIs occur each year in the United States. Extra costs due to bloodstream infections among survivors averaged greater than $40,000 per patient.

Hospital-acquired infection rates now serve as a publicly reported quality indicator. Many states in the U.S. currently require mandatory reporting of CR-BSIs to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and some states have made hospital-specific data publicly available. These publicly reported infection rates are based on the National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) surveillance definition (Table 136-2). As of October 1, 2008, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) no longer reimburses hospitals for costs associated with some hospital-acquired conditions, including CR-BSIs.

| Laboratory-confirmed bloodstream infection requires one of the following criteria: |

|

| Clinical sepsis is defined by either of the following criteria: |

|

The organisms most commonly causing BSIs include coagulase-negative staphylococci (31%), Staphylococcus aureus (20%), Enterococcus species (9%), Candida species (9%), and Escherichia coli (6%) (Table 136-3). The emergence of coagulase-negative staphylococcal infections and Candida species as virulent organisms can be attributed to increased use of intravascular catheters and the selection pressure created by broad spectrum antibiotic use.

| Percentage of BSIs | ||

|---|---|---|

| Pathogen | Total | ICU |

| Coagulase-negative staphylococci | 31.3 | 35.9 |

| Staphyloccocus aureus | 20.2 | 16.8 |

| Enterococcus species | 9.4 | 9.8 |

| Candida species | 9.0 | 10.1 |

| Escherichia coli | 5.6 | 3.7 |

| Klebsiella species | 4.8 | 4.0 |

| Enterobacter species | 4.3 | 4.7 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 3.9 | 4.7 |

| Acinetobacter baumanii | 1.7 | 2.1 |

| Serratia species | 1.3 | 1.6 |

Susceptibility to CR-BSIs is increased by a number of intrinsic host factors including malnutrition, burns, loss of skin integrity, neutropenia, extremes of age, severity of underlying illness, and immunosuppression. The single most important extrinsic factor related to development of primary BSIs is the catheter itself. Peripheral intravenous catheters have the lowest associated rate of infection (0.5 per 1000 catheter days), while pulmonary artery catheters have the highest rates of CR-BSIs (3.7 per 1000 catheter days), followed by central venous catheters (2.7 per 1000 catheter days for nonmedicated, nontunneled central venous catheters).

Measures indicated for the prevention of catheter-related blood stream infections:

|

A number of measures can be employed for the prevention of CR-BSIs. Some of the most effective efforts to reduce CR-BSIs include (1) appropriate site selection for the catheter, (2) use of proper skin antiseptic agents, (3) use of maximal sterile barrier precautions during the procedure (Table 136-4), (4) early central catheter removal when no longer needed, and (5) use of antimicrobial-impregnated catheters. Table 136-1 summarizes the elements of the IHI’s central line bundle for reduction of CR-BSIs. The insertion of catheters into the subclavian vein has been associated with a significantly lower rate of infection compared to the femoral vein in a randomized controlled trial. Observational data suggest that the subclavian site is also associated with a lower risk of infection than the internal jugular site. However, no single randomized controlled trial has compared the infection risk for all three insertion sites. Since the subclavian site may be associated with higher rates of mechanical complications such as bleeding and pneumothorax, decisions regarding site selection for CVC insertion should take into account the clinical circumstances of the individual patient.

Skin antisepsis at the catheter insertion site should be performed with 2% aqueous chlorhexidine gluconate. Tincture of iodine, an iodophor, or 70% alcohol may be used as alternatives if chlorhexidine is contraindicated, but is less effective than chlorhexidine in infection prevention. Maximal sterile-barrier precautions should always be used during catheter insertion (Table 136-4).

|

The use of antimicrobial-impregnated catheters significantly reduced the rate of CR-BSIs and reduced overall medical costs in randomized clinical trials. Three such types of catheters are currently available: chlorhexidine and silver sulfadiazine impregnated, platinum and silver impregnated, and minocycline and rifampin impregnated. CDC guidelines recommend the following; (1) use of an antimicrobial- or antiseptic-impregnated central venous catheter (CVC) in adults whose catheter is expected to remain in place more than five days if an institution’s rate of CR-BSI remains high, or above the institutional goal, despite education of staff who insert and maintain catheters; (2) use of maximal sterile barrier precautions; (3) and use of 2% chlorhexidine preparation for skin antisepsis during CVC insertion.

CVCs should be removed promptly when they are no longer needed or when a peripheral IV can be reasonably inserted and serve the same function as the CVC. Maintaining a CVC when it is not absolutely necessary increases the risk of bacterial colonization and subsequent CR-BSIs over time. Routine catheter changes do not reduce the risk of CR-BSIs, and routine guidewire catheter exchanges may actually increase the rate of infections. Therefore, routine or scheduled CVC changes should not be performed. Rather, catheters should be changed only when concern arises for infection or catheter malfunction. If a catheter infection is suspected and a CVC is still needed, a new catheter should be placed at a different insertion site. Antibiotic ointments promote emergence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria when applied to catheter-insertion sites and therefore should be avoided.

Clinical manifestations of CR-BSIs are often limited to fever, but more specifically can include inflammation or purulence at the site of catheter insertion and bacteremia with no apparent source. The diagnosis of CR-BSIs requires microbiological data to fulfill the CDC criteria for a laboratory-confirmed bloodstream infection (LCBI).

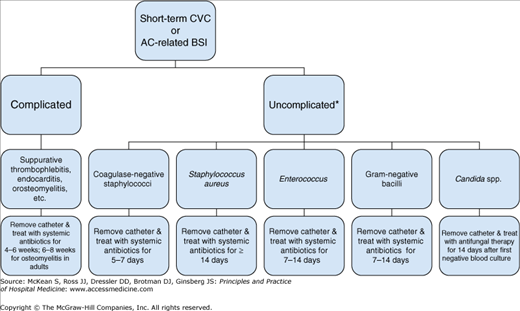

When a CR-BSI is suspected in a patient with fever and a CVC in place, the possibility of bacteremia should be evaluated with two cultures of blood from peripheral sites. A positive blood culture from the central venous catheter does not differentiate catheter colonization or hub contamination from a true CR-BSI. A negative blood culture from the catheter makes a CR-BSI unlikely. When diagnosis of a CR-BSI is highly suspected or confirmed-either clinically or microbiologically-the catheter should be removed immediately and antibiotics should be rapidly initiated. When the organism is identified antibiotics should be tailored to the sensitivity of the organisms grown in culture (Figure 136-1).

Figure 136-1

Algorithm for management of patients with short-term CVC-related or arterial catheter-related blood stream infection. AC, arterial catheter; BSI, blood stream infection; CVC, central venous catheter. *Uncomplicated BSI = resolution of BSI within 72 hours; no intravascular hardware; no evidence of endocarditis, suppurative thrombophlebitis, or S. aureus infection; no active malignancy; and no immunosuppression.