KEY POINTS

Fundamental to improving patient safety is the ability to design systems of care that reliably deliver evidence-based interventions and reduce preventable harm.

Translating evidence effectively into practice involves four key processes:

Summarizing the evidence

Identifying local barriers to compliance

Measuring performance

Ensuring that all patients receive the therapy

A culture of teamwork is vital to improving the quality and safety of care provided to patients.

Significant investment in a patient safety infrastructure is required to fulfill a commitment to safe and high-quality care.

Chosen quality measures should be clinically important, scientifically sound (valid and reliable), useful, and feasible.

An ICU quality and safety scorecard can be developed locally to demonstrate a broad overview of patient safety performance over time, or relative to a benchmark.

A QUESTION OF SAFETY

A decade after the To Err Is Human report,1 the global health care community still struggles to state definitively whether patients under our care are safer. An estimated 98,000 fatalities result from medical errors every year in the United States.2 That number at least doubles if nosocomial infections and other sources of preventable harm are included. This statement is true despite amazing advances in biomedical science that have led to cutting-edge, lifesaving therapies—in part because patients receive only about 50% of recommended evidence-based interventions.3 Although the epidemiology of preventable harm is an immature science, preventable death is a leading cause of death. In addition to increased patient morbidity and mortality, this crisis of patient safety has increased health care costs and lowered public confidence in health care.

PREVENTABLE VERSUS INEVITABLE HARM

The past 10 years have seen a national focus on reducing adverse events, with an increase in research and interventions designed to ensure that patients are receiving safe and high-quality care. Unfortunately, most investment and interest in patient safety has been reactive in nature, addressing egregious, although relatively rare, examples of preventable harm, such as operating on the wrong body part. Other types of preventable harm are more common yet also more nuanced. Within the critical care unit, the acuity and complexity of patient disease lead many to believe that complications and morbidity are inevitable. Central to advancing patient safety improvements and optimizing care delivery is the ability to distinguish preventable harm from inevitable harm.4

In commercial aviation, all fatal crashes are deemed preventable. The implicit idea of preventable harm is that an error occurred that caused harm, but if the error had been prevented, no harm would have occurred. Health care differs substantially from aviation because it is complex and dynamic, and patient conditions not always controllable. Despite receiving the best-known medical therapies, some patients will inevitably die or sustain complications. With ever-advancing scientific knowledge and often expensive technologies, what is inevitable now may be preventable in the future.

Valid measures of preventable harm require clear definitions of the event (numerator) and those at risk for the event (denominator), plus a standardized surveillance system to identify both indicators.5 If the harm (eg, mortality from acute myocardial infarction or pneumonia) is only partially preventable (as most is), we will need methods to dissect inevitable from preventable harm.6,7

Clinicians have labeled virtually all harm as inevitable for decades. They did so partly because false-positive events (truly inevitable cases labeled as preventable) did not help them learn and improve care. Clinicians most often reviewed and learned about morbidity and mortality alone or with other physicians, focusing more on individual skills and actions rather than on systems or team skills. Such an approach is efficient for physicians; it is very specific (truly inevitable cases labeled as inevitable) but it is not very sensitive (truly preventable cases labeled as preventable).

Although this approach misses many patients who experience preventable harm, reviewing the cases identified as preventable can provide useful information. Recent efforts by payers, such as the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), have gone to the other extreme by labeling all harm as preventable. Examples include measures of overall hospital mortality,8,9 the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) global trigger tools for measuring adverse events,10 and most of the “never events” identified by the CMS.11 Both approaches have risks and benefits.

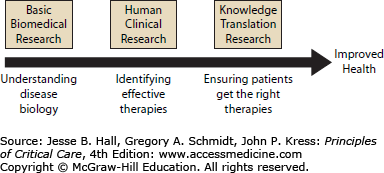

The gap between medical breakthroughs and patient harm remains significant because little has been done to study and improve the actual science of health care delivery (Fig. 5-1). We have made minimal investments in the basic science of patient safety. In the United States, for every dollar the federal government spends on traditional biomedical research, they only allocate 2 cents to research ensuring patients actually receive these treatments.12 Directing resources to advance the science of safety would allow us to better understand the causes of harm, would support the design and testing of interventions to reduce harm, and would promote robust evaluation of the effects of harm.4 Instead, examples of large-scale quality improvements are rare and methods to evaluate progress in quality are virtually nonexistent. This lack of data to analyze, understand, and ultimately improve health care is a complex local and national problem. Most importantly, patients remain at risk of harm.

Fundamental to improving patient safety in the intensive care unit is the ability to design systems of care that reliably deliver evidence-based interventions and reduce preventable harm. Achieving this objective at the local level will require an institutional investment of resources and a reordering of priorities to create and support a true culture of safety. With these goals in mind, it is imperative to use a systematic and multidisciplinary approach and involve all stakeholders.

In strategizing such an approach, it will help if a conceptual framework of safety issues and solutions is created to guide team efforts and ensure common points of dialogue. Dy and colleagues13 have described a consensus classification for patient safety practices in an effort to provide a common language for interpreting patient safety literature. Another approach, categorizing patient safety efforts into general themes, can be useful in focusing efforts to improve the culture of safety within a particular intensive care unit. For example, the following project framework14 can serve as a starting point for a unit-based safety program:

Translating evidence into practice: With the majority of research funding and efforts to date focused on understanding disease mechanisms and identifying effective therapies, there is little evidence describing how to effectively, efficiently, and safely deliver these therapies to patients. Thus, errors of omission (failure to provide evidence-based therapies) that result in substantial preventable harm to patients represent a significant challenge for health care in general, for the individual hospital or critical care unit. Multiple methods seek to increase the reliable delivery of evidence-based therapies to patients. These methods include evidence-based medicine and clinical practice guidelines, professional education and development, assessment and accountability, patient-centered care, and total quality management. Unfortunately, most of these efforts focus exclusively on changing the physician’s behavior. Yet physicians are part of a health care team, and little research has assessed how an entire team can improve the reliability of care.

A four-step process has been developed and successfully used to reliably translate research into practice within the intensive care unit.15,16 This model engages an interdisciplinary team to assume ownership of the improvement project, is based on evidence and performance measurement, and creates a collaborative culture that is essential for sustaining results. The steps are described below with an example of best practices for ventilation of acute lung injury patients.

Summarize the evidence: Medicine traditionally summarizes research evidence into practice guidelines that are scholarly but often impractical for bedside use. Guidelines fail to prioritize lengthy lists of recommendations, are often ambiguous, and may not guide practical clinical decision making. To change practice, the evidence must be concisely summarized into several key interventions described in an unambiguous manner. For example, the evidence supports the use of lung protective ventilation (LPV) for patients with ALI, which can be concisely defined as providing a tidal volume 6 mL/kg of predicted body weight (based exclusively on patient sex and height) and a plateau pressure of <30 cm H2O.17,18

Identify local barriers to practice compliance: Once key interventions are identified, the next step is to actively investigate and remedy local barriers to effective implementation (walking through the process). This is achieved by attempting to implement the practice (documenting all necessary steps), observing others doing it, and asking them about difficulties. Such a process can reveal where defects are likely to occur or where specific systems do not support evidence-based practice—in short, identifying why it is sometimes difficult for clinicians to comply with recommended practices. For example, intensivists may be aware of and agree with LPV use, but find it difficult to know if they are actually compliant.19-25 Moreover, accurate measurement of the patient’s height is necessary in calculating predicted body weight, but height is frequently missing from the patient chart, resulting in unintentional noncompliance with LPV.19,24-26

Measure performance: Once an intervention has been chosen and specific practice behaviors have been developed, performance should be measured to evaluate how frequently patients who should receive a specific therapy actually receive it (process measures), or evaluate whether patient outcomes have improved (outcomes measures). Both types of performance measures have strengths and weaknesses. In the ALI case example, compliance with LPV varies with changes in ventilator settings during a patient’s ICU stay. Therefore, researchers must define the timing and frequency of measuring LPV, and determine what ventilator settings should be included in the definition of compliance. In general, more frequent measures will provide a better but burdensome understanding of performance over the patient’s entire ICU stay.

Ensure all patients receive the therapy: To change practice, quality improvement teams can undertake a four-step process that involves engaging, educating, executing, and evaluating. Engage clinicians by using local estimates of patient harm so clinicians recognize the impact of noncompliance with evidence-based practices in their clinical area. For ALI, this could be estimating the number of preventable deaths based on prevalence of LPV nonuse in ALI patients in an ICU. Clinician education is important to ensure they know the evidence, agree with it, and understand the actions needed to comply with the evidence. Executing the intervention to improve compliance with the evidence often requires some fine-tuning of the process to overcome local barriers. Change can often be achieved by using a checklist or other interventions to standardize care,27 or by defining a “care bundle” to ensure that all patients meeting certain criteria receive the intervention(s). For ALI, that could mean requiring that patient height be recorded in the electronic medical record, stocking tape measures in each patient room, modifying rounding templates to prompt clinicians to record and report plateau pressure and tidal volume measured in mL/kg of predicted body weight, or using prescribed order sets and decision-support tools when providing LPV.20,22,25,26 Performance should be evaluated with timely and accurate measures and reported back to clinicians.

Working as a team: Although measuring harm rates and using effective therapies are important for safety, they are insufficient without teamwork and a culture that embraces safety.28 An organization’s ability to change is driven by its culture, which in turn has a significant impact on safety.29-31 Indeed, failures in communication, a pertinent element of culture, are a common cause of sentinel events in health care in the United States.32

The Comprehensive Unit-Based Safety Program (CUSP) is a comprehensive and longitudinal program designed to improve local culture and safety.33 It evolved from an eight-step33 to a five-step34 program (Table 5-1), and is supported by a Web-based project management tool.35 The CUSP is designed to be adopted by individual work units or care areas. Everyone that provides care within the unit is involved in CUSP, from physicians to nurses, pharmacists, administrative clerks, and other support staff. The program also leverages support from senior leaders in the health care organization to provide assistance in garnering resources.

The CUSP model provides a knowledge base about the science of safety so frontline staff can recognize safety hazards in the workplace and design interventions to eliminate these hazards. Moreover, it emphasizes the importance of effective teams, trains staff to use a practical tool to investigate and learn from defects, and offers tools to improve teamwork and communication both within and between patient care areas. Implemented initially in two surgical intensive care units at The Johns Hopkins Hospital in 2001, the program produced a significant reduction in ICU length of stay and medication errors as well as a potential improvement in nurse turnover.33,36,37

While CUSP provides a platform for individual staff to share experiences with everyone in the unit and empowers the group to solve local problems in care delivery, embedding these interventions in the daily work routine can also enforce positive changes in the unit’s safety culture. For example, creating interdisciplinary rounds in the unit offers a platform for nurses to voice concerns, seek clarification about a patient’s management, and gain autonomy as the bedside caregiver. Interdisciplinary rounds lessen the hierarchy that usually occurs between physicians and nurses, a hierarchy that causes ineffective collaboration among clinical disciplines and prevents individuals from acting upon safety concerns. Implementation of a daily goals sheet (Fig. 5-2) can also help improve communication and collaboration among nurses and physicians for individual patients, plus leads to more effective coordination of daily care plans and efficient movements of patients to discharge.38

Learning from defects: Retrospective identification of medical errors and in-depth analysis of contributing factors provides an opportunity to learn from, rather than just recover from harm. Knowledge is a better defense against the recurrence of the same or a similar harm and is essential to promoting a culture of safety. The Institute of Medicine has targeted incident reporting systems as a method to collect defect information, investigate the causes, and improve safety.1,39 To make incident data useful, health care organizations can learn from reported mistakes through formal (root cause analysis) or informal (case review) methods.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree