Key Clinical Questions

What is a pressure ulcer and how do you stage severity?

How do you assess individual risk for the development of pressure ulcers?

What measures are effective in pressure ulcer prevention?

How should pressure ulcers be cleansed, debrided, and dressed?

What role do adjunctive therapies have in pressure ulcer treatment?

Introduction

Pressure ulcers, or “bedsores,” are a key clinical indicator of quality of care in hospitals. Their occurrence is widely seen as a marker for substandard care, triggering anger and sometimes litigation on the part of patients and families. However, they remain common in hospitalized patients. In 1993, pressure ulcers were diagnosed during 280,000 hospital stays in the United States, a number that rose to 455,000 in 2004. Up to 15% of elderly patients develop pressure ulcers within the first week of hospitalization. Mortality may be as high as 60% for older persons with pressure ulcers in the year after hospital discharge.

Pressure ulcers are also expensive, with an average charge per stay of $43,180. In 2007, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) made payouts of more than $11 billion for beneficiaries admitted to hospitals who developed stage III and stage IV pressure ulcers. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services subsequently stopped reimbursement for hospital-acquired stage III and stage IV pressure ulcers in October 2008.

Pathophysiology

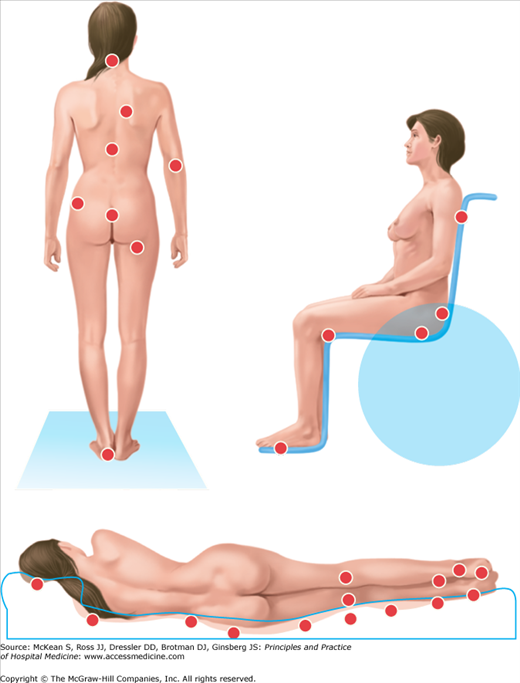

Pressure ulcers are focal injuries of skin and subcutaneous tissue resulting from pressure, shear forces, friction, or some combination of these. They most often overlie bony prominences of the pelvis and lower extremities, such as the sacrum, greater trochanter of the hip, and heels, but they may appear in other locations, depending on patient positioning (Figure 144-1).

Tissue ischemia occurs when external pressures exceed perfusion pressures. Normal blood pressure within capillaries ranges from 20 to 40 mm Hg; 32 mm Hg is considered average. An external pressure less than 32 mm Hg usually suffices to prevent pressure ulcers. However, capillary blood pressure may be less than 32 mm Hg in critically ill patients due to hemodynamic instability and comorbid conditions.

Frictional forces, like those generated between the heels and bedsheets, can lead to blisters and skin breakdown, favoring the development of pressure ulcers. Bedbound patients are also prone to shear forces, which occur when bone and soft tissue move relative to the skin, which is held in place by friction.

Prevention

Pressure ulcer prevention requires a team effort, involving physicians, nurses (including wound, ostomy, and continence nurses), dietitians, and physical therapists. Studies have demonstrated that comprehensive pressure ulcer prevention programs can decrease incidence rates, although not to zero. For optimal effectiveness, pressure ulcer prevention must begin as soon as patients enter the hospital. There are five basic components to comprehensive pressure ulcer prevention: risk assessment, skin care, mechanical loading, support surfaces, and nutritional support.

The identification of patients at greatest risk of pressure ulcers involves the use of a risk assessment tool, skin assessment, and clinical judgment. More than 20 pressure ulcer prediction tools are used throughout the world, with the most popular being the Braden, Norton, and Waterlow scales. The Braden Scale for Predicting Pressure Sore Risk is the most widely used in U.S. hospitals. (The copyrighted tool is available at http://www.bradenscale.com/images/bradenscale.pdf.) The Braden Scale is designed for use with adults, and consists of six subscales: sensory perception, moisture, activity, mobility, nutrition, and friction and shear. Total scores on the Braden Scale range from 6 (high risk) to 23 (low risk); a score of 18 is the cut-off score for onset of pressure ulcer risk.

There is general consensus from most pressure ulcer clinical guidelines to do a risk assessment on admission, at discharge, and whenever the patient’s clinical condition changes. Skin assessment should also be correlated with risk assessment. Close attention should be paid to greater trochanters, heels, sacrum, and coccyx, as more than 60% of all pressure ulcers occur at these locations.

The skin of patients at risk of pressure ulceration should be inspected regularly for erythema. This includes pressure points, as well as areas of contact with medical devices, such as catheters, oxygen tubing, ventilator tubing, and semi-rigid cervical collars, as these may also cause ulceration. Pain over an erythematous area may herald skin breakdown. It is not always possible to see redness on darkly pigmented skin. However, depending on the degree of pigmentation, erythema may appear blue or purple, compared to adjacent skin. Erythema should be categorized as blanching or nonblanching. Localized heat, edema, and induration over the pressure points are additional warning signs for pressure ulcer development. The frequency of inspection may need to be increased in response to any deterioration in overall patient condition.

Protecting skin from excessive moisture with barrier paste or other products is essential, as the mechanical properties of the stratum corneum may be changed by moisture and warmth. Massaging areas of reddened skin should be avoided, as these may contain damaged blood vessels or fragile skin. Skin emollients to hydrate dry skin should be considered.

One of the most important preventive measures is decreasing mechanical load and pressure exposure. High pressures over bony prominences for short periods of time and low pressures over bony prominences for long periods of time are equally damaging. Repositioning frequency should be determined by the patient’s skin condition and tissue tolerance, level of activity and mobility, general medical condition, overall treatment objectives, and support surfaces applied to the bed or chair. Turning and repositioning hospitalized patients every two hours while in bed, and every one hour while seated, is reasonable for most hospitalized patients. Those who are critically ill may require hourly repositioning, while stabilized patients on specialty beds, such as low air loss or air fluidized, may only need repositioning every four hours.

The patient should be repositioned to relieve or redistribute pressure. Transfer aids, such as the Hoyer lift or trapeze, that reduce friction and shear forces should be used. Avoid positioning the patient directly on a bony prominence or directly onto medical devices, such as tubes or drains. The 30-degree-tilt position and the standard 90-degree side-lying position seem to be equivalent in protection against the development of pressure ulcers.

Pressure should be distributed as evenly as possible across the patient’s body to reduce the incidence of pressure ulcers. The use of support surfaces may assist in pressure redistribution. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services have divided support surfaces into three categories for reimbursement purposes. Group 1 devices are static and do not require electricity. Static devices include air, foam (convoluted and solid), gel, and water overlays or mattresses. These devices are ideal when a patient is at low risk for pressure ulcer development. The devices have some drawbacks: foam may degrade and lose its stiffness over time, and gel mattresses can increase skin heat and moisture. Group 2 devices are dynamic and powered by electricity or pump action. These devices include alternating and low-air-loss mattresses. These mattresses are better for patients at moderate to high risk for pressure ulcers, or who have full-thickness pressure ulcers (stage III and stage IV). Critically ill patients are excellent candidates for this group of support surfaces.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree