TOPICS

1. Heart surgery patients and consent

3. Coronary stents or coronary artery bypass?

6. Preoperative red flags and what (if anything) to do about them

It is often said that the anesthesiologist is the internist of the operating room (OR). By extension, the cardiac anesthesiologist becomes the OR’s cardiologist. While it is certainly true that anesthesiologists must have knowledge of medicine in general and cardiology in particular, the practice of cardiac anesthesia is a unique discipline unto itself. Although cardiac anesthesiologists must have knowledge of why someone is being taken to cardiac surgery, they will not be the ones to decide if surgery is indicated or not. Rather, cardiac anesthesia staff must review the totality of the patient’s cardiac and medical history to determine the best approaches to manage sick patients perioperatively. This chapter will briefly examine how someone is referred for cardiac surgery and the essential elements of preoperative evaluation necessary for patient management.

HEART SURGERY PATIENTS AND CONSENT

Patients of all types present for heart surgery. From the smallest, hypoxemic infant with congenital heart disease to the 90-year-old with critical aortic stenosis, all varieties of patients undergo heart surgery. Even patients undergoing the same type of surgery can vary greatly depending upon their preoperative comorbidities and the impact their disease has had upon their cardiac function. A patient with well-preserved ventricular function presents far different challenges than an individual with a low ejection fraction. Likewise, the patient with intact renal function free of diabetes and lung disease is potentially less problematic than the person afflicted with these comorbidities. In this regard the conduct of cardiac anesthesia parallels that of any anesthetic. A patient’s comorbidities are considered as the anesthetist determines the appropriate anesthetic technique, monitoring, and plan for postoperative management. What is perhaps unique about cardiac anesthesia is that so many of these comorbidities are regularly present; the “routine” cardiac surgery patient is incredibly sick both as a consequence of their primary heart disease as well as the associated illnesses which occur frequently in this patient population.

Generally, the “routine” cardiac surgery patient is designated as an American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) class 4. No one undertakes cardiac surgery on a whim and as such anesthesia consent should be direct and sobering to avoid excessive optimism in patients and their families. All patients are informed of the inherent risk of death, stroke, neurological dysfunction, or renal failure. The risk/benefits of transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) should likewise be discussed with the patient preoperatively. Although the risk of stroke following bypass surgery is low (3%)1 and that of death even lower, cardiac surgery is associated with multiple postoperative morbidities including cognitive dysfunction, renal failure, gut ischemia, and potentially prolonged ICU care. Because both the surgeon and the anesthesia team influence the patient’s hemodynamic performance it is often difficult to discern whether surgery or anesthesia is responsible for an adverse outcome. Ideally both the surgery and cardiac anesthesia groups function as a team sharing the joy when difficult patients are safely managed and sharing the anguish when the inevitable death or brain injury occurs. Anesthesiologists entering into cardiac anesthesia practice should be aware that outcomes are often disappointing and there is the ever-present risk of litigation even if the anesthesiologist has practiced according to all possible standards of care. Unfortunately, adverse events happen to people during cardiac surgery as a consequence of both patient illness and the numerous techniques necessary to repair the dysfunctional heart. Careful documentation and frank discussions with patients and their family are essential in cardiac anesthesia practice.

CARDIAC SURGERY AND GENDER

Although patients of all ages, races, and genders present for cardiac anesthesia and surgery, access by all demographic groups to cardiac surgery therapies may not be equal.2 Disadvantaged groups may have less access to invasive cardiac surgery procedures.3–5 Female patients are at risk for higher mortality when undergoing coronary bypass surgery. Why such discrepancies in outcomes and access? It is possible that female patients are at disadvantage because they present at an older age with poorer ventricular function as well as more comorbid disease states such as diabetes and renal dysfunction. Patients from less well-off communities may have less access to surgery or are perhaps treated in less well-equipped hospitals.

Also, female patients following coronary artery surgery may have a longer period of intubation and length of hospital stay.6 This may be secondary to the increased incidence of comorbidities in female cardiac surgery patients.

CORONARY STENTS OR CORONARY ARTERY BYPASS?

The increased use of angioplasty and stents to treat coronary artery disease has reduced the number of patients presenting for heart surgery. The otherwise healthy patient with preserved ventricular function and angina in need of a two-vessel bypass is increasingly rare in the cardiac surgery operating room. Many patients undergo various percutaneous coronary interventions (PCIs) as first-line therapy upon presentation with anginal pain. Many studies have tried to highlight the risks and benefits of coronary artery bypass surgery versus medical therapy versus bare metal stents versus drug eluting stents for the definitive treatment of coronary disease. As catheter-mediated valve replacement becomes even more perfected, debate will likely follow on the benefits and risk of valve surgery versus catheter-mediated valve replacement.

Serruys et al prospectively randomized 1800 patients with severe three vessels or left main coronary artery disease to cardiac surgery or PCI assuming that both techniques in the opinion of the patient’s cardiologist and cardiac surgeon could achieve equivalent anatomical revascularization.7 They demonstrated that the rates of adverse cardiac or cerebrovascular events at 1 year were higher in the PCI group secondary to the increased need for repeat revascularization efforts in those patients treated with stents as opposed to surgery. The medicine, angioplasty, or surgery study (MASS) II trial randomized 611 patients with coronary disease to surgery, PCI, or medical therapy (MT).8 At 5 years the three approaches resulted in similarly low death rates. However, patients undergoing surgery required fewer additional procedures during the study period. A meta-analysis looking at four trials comparing stent versus bypass surgery revealed that the overall incidence of adverse cardiac or cerebrovascular events was lower in the surgery group secondary to the reduced need in operated patients to perform repeat revascularization procedures.9 However, survival at 5 years was not found different between the groups.

The risk of stent thrombosis with both bare metal and drug eluting stents is well known.10 Patients following stent placement are treated with various antiplatelet regimens to prevent stent thrombosis. The anesthesia staff should not take it upon themselves to discontinue antithrombotic or antiplatelet medication perioperatively in patients treated with stents. Only the patient’s cardiologist and surgeon should determine collectively if antiplatelet medications should be discontinued perioperatively and if surgery is to be considered in a patient with prior stent placement. However, patients requiring antiplatelet therapy perioperatively are likely to require large amounts of blood products during surgery and the anesthesiologist should be prepared for this situation.

Frequently, the cardiac patient coming for revascularization nowadays will have undergone PCI at some point in the past. Surgery is elected when lesions are not amenable to PCI or the patient has combined coronary arterial and valvular heart disease. Such patients may have presented with recurrent myocardial infarctions prior to each stent placement. Over time, patients can develop ventricular dysfunction from recurrent myocardial ischemia and infarction.

CARDIOLOGY EVALUATION

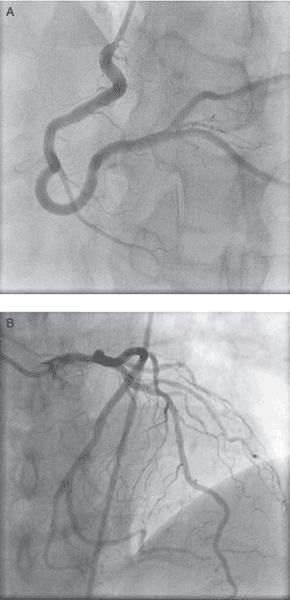

Patients with cardiac angina, positive stress tests, nuclear medicine scans suggestive of myocardial ischemia, valvular heart disease, and ventricular dysfunction are routinely taken to the cardiac catheterization laboratory for diagnostic purposes. Catheterization demonstrates the coronary vasculature and pathology. PCI is usually performed at the time of diagnosis or the patient is referred for surgery. Figure 1–1 demonstrates the normal left and right coronary anatomy. Figure 1–2 reveals occlusions in both the left and right circulations (Video 1–1). Coronary artery lesions are frequently treated with percutaneously placed stents (Video 1–2). When the patient’s anatomy does not favor PCI, patients are referred for surgery. Newer technologies using magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography have been employed to better visualize the coronary arteries.11,12 The role of these technologies in the diagnosis and treatment of coronary artery disease is likely to increase. However, at present cardiac catheterization remains the most common pathway by which patients find their way to surgery.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree