Introduction

Hospitalists and internists are frequently called upon to perform preoperative medical consultations, and cardiac risk assessment is what is most often requested. Preoperative evaluation is now part of the core curriculum for Hospital Medicine, but when surveyed a number of years ago, many hospitalists felt inadequately trained to do this.

Preoperative cardiac risk assessment has evolved over the past 40 years from a simple global assessment of a patient’s physical status (the ASA classification) to multivariate risk analyses (Goldman, Detsky) to a simplified scoring system (Lee RCRI) to guidelines from the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association, American College of Physicians (ACC/AHA, ACP). The most current of these is the ACC/AHA guidelines for perioperative cardiac evaluation and management, originally published in 1996 and updated in 2007 to incorporate the RCRI factors. Using these guidelines and selective cardiac testing (pharmacologic stress tests), physicians are now better able to provide a more accurate assessment of perioperative risk, and the focus has turned to risk reduction strategies. These include revascularization by coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) or percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), medical therapy (beta-blockers, alpha-agonists, statins), and other intraoperative measures (normothermia, anesthetic technique). Although surgical and anesthetic techniques have improved and perioperative cardiac events have decreased, operative mortality and cardiac morbidity remain significant, especially among high-risk patients or high-risk procedures.

Preoperative Risk Indices

Goldman and colleagues published the first large prospective multivariate analysis of preoperative cardiac risk. They identified nine independent predictors of death or major postoperative cardiac complications. These risk factors were assigned points based on their relative importance, and the event rates were correlated with the point total in this risk index. Detsky and colleagues modified this risk index by expanding the list of risk factors and combining this with the pretest probability of complications based on the risk of the surgery itself. Eagle and colleagues identified five factors—age, diabetes mellitus (DM), angina, myocardial infarction (MI), and heart failure—associated with perioperative cardiac events and used these to stratify risk and decide when to do further cardiac testing. Most recently Lee and colleagues identified and validated six factors associated with increased risk of perioperative complications. These factors were high-risk surgery, coronary artery disease (CAD), heart failure, cerebrovascular disease (stroke or transient ischemic attack), DM requiring insulin, and renal insufficiency (creatinine > 2.0 mg/dL). These studies, using simple clinical evaluation (history, physical examination, and basic laboratory studies) found many similar factors predicting increased risk of perioperative cardiac complications and helped refine preoperative risk stratification.

Clinical Risk Factors

|

A detailed history and focused physical examination are key in clinical risk assessment, and a few basic diagnostic tests may also be helpful. Current risk assessment is usually based on the Lee RCRI and the ACC/AHA guidelines, which now include the RCRI factors. What the ACC previously defined as major clinical predictors are now called active cardiac conditions. These are unstable coronary syndromes (MI < 30 days, unstable or severe angina), decompensated heart failure, hemodynamically significant arrhythmias, or severe (symptomatic) valvular heart disease. The group previously called intermediate clinical predictors is now called clinical risk factors and includes five of the six Lee RCRI factors (MI > 30 days, stable mild angina, compensated or history of heart failure, DM, renal insufficiency, and stroke)—the type of surgery is considered separately. The so-called minor risk predictors in the 2002 guidelines were dropped with the exception of cerebrovascular disease, which was moved up to the clinical predictor group. These minor predictors included some factors typically associated with risk of developing CAD (hypertension, dyslipidemia, cigarette smoking), but most studies found that these factors were not significant predictors of postoperative cardiac complications.

|

Procedural Risk

Independent of the patient’s clinical risk factors, the type of surgery has its own inherent risk that needs to be taken into account. This concept was used in Detsky’s modified cardiac risk index and is also a factor in the ACC algorithm. For example, a patient undergoing cataract surgery, a low-risk operation, is unlikely to have a complication even if the patient’s clinical risk is high. Conversely a patient with no clinical risk factors undergoing high-risk surgery, such as a Whipple procedure, is more likely to have a postoperative complication than would have been predicted based on clinical pretest probability alone. Therefore, the risk of the surgery itself may alter management and influence the decision to do further testing. The ACC defines three groups for surgical risk—vascular, intermediate, and low. The previous designation of high risk has been changed to vascular surgery to reflect that the preponderance of evidence for cardiac testing was done for patients undergoing aortic and major vascular surgery, and the approach to these patients may be somewhat different than that for nonvascular surgery. The intermediate risk category includes most intrathoracic, intraabdominal, head and neck, orthopedic, and urologic procedures as well as some lower-risk vascular procedures such as carotid endarterectomy and endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. Low-risk surgery includes procedures not invading the chest or abdomen such as endoscopic or superficial procedures, eye surgery, and breast surgery.

|

Functional Capacity

Goldman and colleagues noted that patients with good exercise capacity, even with mild, stable angina, tend to do well. This follows the concept of the ischemic threshold in which a patient developing ischemia on a stress test at a lower exercise level and with a lower rate-pressure product is at higher risk than someone who can perform 8–10 metabolic equivalents (METS) before developing symptoms. Reilly and colleagues found that a patient’s self-reported exercise capacity correlated with the risk of postoperative complications, and the ACC guidelines use this in their risk assessment algorithm.

|

Laboratory Tests

Many preoperative screening blood tests are performed unnecessarily, but a few may be helpful in assessing cardiac risk. These include measures of renal function, blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine, and glucose (as a screen for diabetes). Unless serum potassium is significantly abnormal (3.0 or > 5.5 mEq), it is unlikely to increase risk or alter management. Anemia has been noted as a risk factor in some studies, but there is no evidence that treating it with transfusions alters risk. An electrocardiogram (ECG) looking for evidence of CAD or conduction defects may be of value in at-risk patients. Other findings can either be identified by clinical exam (arrhythmias) or don’t change management (left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH), nonspecific ST-T changes).

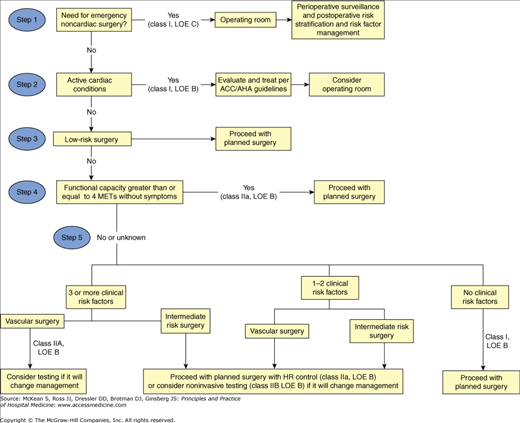

Acc/Aha Algorithm

The ACC developed a stepwise approach to preoperative cardiac risk evaluation using the information obtained from the history, physical examination, and laboratory tests (Figure 51-1). The underlying theme is to minimize testing and not to order a test if the result will not change management. The approach is as follows:

Is the surgery emergent (and I tend to include urgent. meaning within 24 hours)?

If it is, time does not permit diagnostic testing or revascularization and the patient will proceed to surgery. In the short time period available, the physician can try to medically optimize the patient’s problems.

Assuming surgery is not emergent, does the patient have any of the active cardiac conditions?

If so, elective surgery should be delayed for further diagnostic workup and therapy. Most patients do not have these conditions.

Is the surgery low risk?

If it is, the patient should proceed to surgery without any further testing or intervention because we cannot further reduce risk that is already low (<1%).

If not scheduled for low-risk surgery, does the patient have adequate exercise capacity (≥4 METS)?

If so, for the most part, these patients will do well and do not need to undergo further cardiac testing.

Assuming the answers to all of the previous questions were no, the next step is to determine the patient’s clinical risk factors.

If there are no clinical risk factors, the patient should proceed to surgery with no further testing.

If the patient has one or two risk factors, the guidelines recommend proceeding to surgery with heart rate control; however, they do say you can consider noninvasive testing (NIT) if the results will change management.

The recommendations are the same for three risk factors and nonvascular surgery; however, for three or more risk factors and vascular surgery, the recommendation is to consider NIT.

This last step allows for individualizing management, but it is also somewhat vague and may lead to significant differences in opinion and approach.

Figure 51-1

ACC/AHA Cardiac Evaluation and Care Algorithm for Noncardiac Surgery. (Reproduced, with permission, from Fleischer LA, Beckman JA, Brown KA, et al. ACC/AHA 2007 guidelines on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and care for noncardiac surgery: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;54:e169.)

Diagnostic Tests

|