90% false-positive rate

Normal > 7 cm

When combined with Mallampati: sensitivity 81%, specificity 97%

Class B: lower incisors level with upper

Class C: lower incisors cannot meet upper

Occipital finger higher = severe limitation

(Complicated therefore less practical)

Head and neck movement

Jaw movement

Receding mandible

Buck teeth

(each factor scored 0, 1 or 2)

Sensitivity 88%

* Sensitivity = probability of identification of true positives, i.e. detects a difficult case that is difficult. When low, lots of false negatives occur meaning you fail to predict difficult cases.

Specificity = probability of identification of true negatives, i.e. detects a normal case that is normal. When low, lots of false positives occur.

Positive predictive value = the probability of a positive result being a true positive, i.e. it is the % of patients found to be difficult out of all those predicted to be difficult.

Preoperative investigations (NICE guidelines)

In 2016 NICE updated their 2003 guidance regarding the use of routine preoperative investigations[3]. The guidance is based on the best available evidence, which in this case is all level IV (expert opinion from the consensus development process and clinical experience). This makes the recommendations grade D. The guidance tailors the recommended investigations according to:

Patient’s ASA grade

Co-morbidity

The grade of complexity of the surgery (see Table 23.2 below).

Surgical complexity

| Surgical complexity | Examples |

|---|---|

| Minor (grade 1) | I&D abscess |

| Intermediate (grade 2) | Inguinal hernia, tonsillectomy, arthroscopy |

| Major (grade 3 or 4) | TAH, TURP, Joint replacement, bowel resection |

The tests are summerised in the form of colour-coded table using a traffic light system: red = not recommended; yellow = consider; green = recommended.

Table 23.3 above summarizes the green and yellow recommendations which are further condensed onto the preoperative assessment checklist. These guidelines cover elective surgery only and urgent or emergency cases are likely to require additional investigations

Routine preoperative investigations (bold = recommended; italics = consider)

| Complexity of surgery | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| ASA | Minor | Intermediate | Major |

| 1 | FBC, ECG if > 65 & not within 12 months, U&E if at risk of AKI* | ||

| 2 | ECG, U&E if at risk | FBC, U&E, ECG | |

| 3 or 4 | U&E if at risk of AKI, ECG if no result within 12 months | FBC, U&E, ECG, consider haemostasis tests if chronic liver disease, consider lung function tests. | FBC, U&E, ECG, haemostasis tests if chronic liver disease, consider lung function tests. |

* AKI = acute kidney injury

Patients with diabetes should also have an HbA1c result within 3 months.

Sickle cell test

By adulthood sickle cell disease will be evident. Testing patients may reveal carrier status but this will not affect management and so it is not routinely recommended. Patients should be asked about their own and their family’s sickle cell status to guide management.[3]

Preoperative assessment checklist

Figure 23.1 is a preoperative assessment checklist which summarises the key points in the anaesthetic history and examination and the NICE recommendations for preoperative investigations.

Preoperative assessment checklist.

Operative risk scoring systems

A patient should be considered high risk if their predicted mortality is greater than 5%. The Royal College of Surgeons suggests that the following patients should always be considered high risk.

Patients undergoing major gastrointestinal or vascular surgery who are either:

1) Aged > 50 years;

And undergoing urgent, emergency or redo surgery,

Or have acute or chronic renal impairment (serum creatinine > 130 μmol/l),

Or have diabetes mellitus (even if only diet controlled),

Or have or are strongly suspected clinically to have any significant risk factor for cardiac or respiratory disease.

2) Aged > 65 years.

3) Have shock of any cause, any age group[4].

In 2010 the Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland (AAGBI) published guidelines covering the preoperative management of patients. These guidelines list the following factors for survival prediction: age (risk increases after the age of 10); sex (males 1.7 × > females); socioeconomic class (low social class increases risk); aerobic fitness (increased fitness decreases risk and vice versa) and medical history (1.5 × increased risk with a diagnosis of myocardial infarction, heart failure, cerebrovascular accident, peripheral arterial disease and renal failure)[5].

Multiple scoring systems exist to try and predict the patient’s morbidity and mortality with surgery. None are perfect and they range from the simple (e.g. ASA grade) to the multifaceted (e.g. P-POSSUM).

ASA

- Grade 1:

Normal healthy patient (without clinically important co-morbidity)

- Grade 2:

Patient with mild systemic disease

- Grade 3:

Patient with severe systemic disease

- Grade 4:

Patient with severe systemic disease, constant threat to life

- Grade 5:

Moribund patient who is not expected to survive 24 hours with or without surgery

- Grade 6:

Brain dead patient, organ donation

Revised Cardiac Risk Index

The Revised Cardiac Risk Index was devised in 1999 to predict the risk of a cardiac event in patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery. Each factor is assigned one point.

High-risk surgical procedures

Intraperitoneal

Intrathoracic

Supra-inguinal vascular

History of ischaemic heart disease

History of congestive heart failure

History of congestive heart failure

Pulmonary oedema

Paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnoea

Bilateral rales or S3 gallop

Chest x-ray showing pulmonary vascular redistribution

History of cerebrovascular disease

History of transient ischaemic attack or stroke

Preoperative treatment with insulin

Preoperative serum creatinine > 2.0 mg/dl.

The risk of a major cardiac event (which includes myocardial infarction, pulmonary oedema, ventricular fibrillation, cardiac arrest and complete heart block) is calculated as follows[6]:

P-POSSUM

The Physiological and Operative Severity Score for the enUmeration of Mortality and Morbidity (POSSUM) was originally developed as a retrospective tool. It was found to overestimate mortality and morbidity in the lower-risk population and hence the Portsmouth modification (P-POSSUM) was developed. The parameters used (listed in Table 23.4) should be readily available from the patient’s charts and following discussion with the surgeons.

Variables included in the P-POSSUM score

| Physiological variables | Operative variables |

|---|---|

| Age | Operative severity |

| Cardiac signs | Multiple procedures |

| Dyspnoea | Total blood loss |

| Blood pressure | Peritoneal soiling |

| Pulse | Malignancy |

| Glasgow Coma Scale | Mode of surgery |

| Haemoglobin | |

| White cell count | |

| Urea | |

| Sodium | |

| Potassium | |

| ECG |

The Vascular Anaesthesia Society of Great Britain and Ireland have a useful calculator on their website that predicts POSSUM morbidity and mortality and P-POSSUM mortality[7].

METs

Metabolic equivalents are an important way to assess the physical ability of a patient prior to surgery. This can be tested formally or by asking the patient about their level of exercise and physical ability without restriction or limitations.

One MET is the basal metabolic rate of a 40-year-old 70 kg man, which is an oxygen consumption of approximately 3.5 ml/kg/min[8]. Climbing two flights of stairs is equivalent to 4 METs and inability to do this is associated with increased incidence of post-operative cardiac events[9]. In fact, the number of METs achieved is inversely proportional to anaesthetic risk.

Paediatric anaesthesia

The paediatric population presents a unique set of problems for the anaesthetist preoperatively. The age and the development of the child will affect their level of understanding and dictate the interaction with them and their parents. Cancelling children’s operations is disruptive for the child and other family members. Additionally, a number of factors need to be considered when anaesthetizing the child.

Heart murmurs

It is important to distinguish between the innocent and the pathological murmur as the latter may require cancellation of the proposed operation. Upon discovering a murmur, the chances are that it will be innocent; however, some features may be of greater concern (see Table 23.5).

| Features | Innocent | Pathological |

|---|---|---|

| Cardiac symptoms | Asymptomatic | Symptomatic |

| Timing of murmur | Early systolic Continuous | Diastolic; pansystolic; late systolic |

| Quality of murmur | Blowing; musical; vibratory | Variable; harsh |

| Precordial thrill | Never | Sometimes |

| Variation with posture | Often | Rarely |

If the child is under the age of one, then the finding of a murmur should prompt referral and investigation prior to anaesthesia, even if asymptomatic. In the older child, any additional symptoms require a referral to cardiology.

Upper respiratory tract infections

Upper respiratory tract infections (URTI) are very common in children and will affect the administration of anaesthesia. The main risks of proceeding in a child with a concurrent URTI are laryngospasm and bronchospasm. Postponing surgery may be prudent if the child shows signs of any systemic symptoms (e.g. malaise, fever), purulent nasal discharge, a productive cough, and signs on chest auscultation and in children < 1 year old[10]. Confirmation from the parents that the child has been unwell may also lead to cancellation. Depending on the severity of the URTI, then rescheduling should take place from 2 weeks (mild) to 4–6 weeks (severe) to limit the risk of laryngospasm.

Immunization

The timing of surgery with vaccination has been summarized by the Association of Paediatric Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland.

Inactivated vaccine

Delay surgery by 48 hours to avoid confusion of perioperative and post-vaccination symptoms.

Vaccination can be administrated post-operatively providing child has recovered.

Live attenuated vaccine

No need to delay surgery as long as child is well[11].

Child protection

Every anaesthetist who has contact with children has a responsibility to that child. Within the hospital there will be designated child protection professionals with whom the concerns can be raised and discussed. There will be a person who can be contacted irrespective of the time of day; check who this is within your Trust.

ECG interpretation

This section provides a quick refresher on salient points to remember about ECGs. Firstly, we provide a reminder of basic 12-lead ECG interpretation, information on accompanying symptoms or arrhythmias which require further investigation and, finally, some ECG patterns not to be missed.

| • | Rate: | 300 divided by the number of large squares in between R waves |

| • | PR interval: | 0.12–0.24 ms (3–6 small squares) |

| • | QRS complex: | 0.8–0.12 ms (2–3 small squares) |

| • | Electrical axis: | Lead I and aVF positive – normal axis |

| Lead I positive and II and aVF negative – left axis deviation | ||

| Lead I negative and aVF positive – right axis deviation | ||

| • | Bundle branch block: | Prolonged QRS with RSR pattern, looks like an M in V1, W in V6 – right bundle branch block (MoRRow) |

| Prolonged QRS, looks like a W in V1, M in V6 – left bundle branch block (WiLLiam). |

When presented with an ECG it is important to identify those that will warrant further investigation and, potentially, cancellation. Certain adverse signs in the presence of arrhythmia should prompt immediate treatment. According to the Resuscitation guidelines 2015, these adverse signs are:

Shock – hypotension (systolic blood pressure < 90 mmHg), pallor, sweating, cold and clammy extremities, confusion or impaired consciousness

Syncope

Myocardial ischaemia – typical ischaemic chest pain and/or ECG evidence of a myocardial event

Heart failure – pulmonary oedema and/or raised jugular venous pressure[12].

Bradyarrhythmias with an inherent risk of asystole are: complete heart block with widened QRS complexes; second-degree heart block type 2 and ventricular pauses greater than 3 seconds.

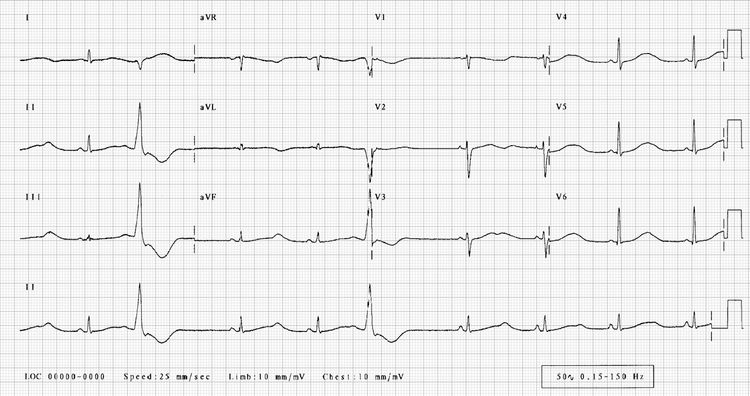

Wolff–Parkinson–White

Additional aberrant muscular tissue in the form of the bundle of Kent conducts more quickly than the AV node and hence, one side of the ventricle is excited early. This results in the following:

Short PR interval

Prolonged QRS deflection on the upslope

Normal length interval between start of P wave and end of QRS[13].

Atrial premature beats have the potential to cause paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardias. There is an increased risk of atrial fibrillation and deterioration to ventricular fibrillation. Perioperatively there needs to be avoidance of drugs and events that may precipitate anterograde conduction via the accessory pathway.

ECG of Wolff-Parkinson-White.

Prolonged QT syndrome

The acquired or congenital electrical abnormality predisposes to syncope and polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. An ECG should be performed on patients with a family history of sudden cardiac death. The abnormality is:

Prolonged QTc > 460–480 ms.

Stop precipitant drugs (including isoflurane and sevoflurane) wherever possible. Electrolyte abnormalities, particularly hypomagnesaemia, should be corrected should deterioration occur. Esmolol is the anti-arrhythmic drug of choice intraoperatively. Phenytoin should be considered post-operatively[14].

ECG of prolonged QT syndrome.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree