CHAPTER 15 PRACTICAL PROCEDURES

GENERAL INFORMATION

Universal infection control precautions

Cuts or grazes on the hands or forearms should be covered with a waterproof dressing while at work. Seek medical advice about any septic or weeping areas.

Cuts or grazes on the hands or forearms should be covered with a waterproof dressing while at work. Seek medical advice about any septic or weeping areas. Single-use gloves should be worn for direct contact with blood or body fluid, broken skin or mucous membranes.

Single-use gloves should be worn for direct contact with blood or body fluid, broken skin or mucous membranes. Full face visors should be worn to protect against blood or body fluids that may potentially splash the face / eyes.

Full face visors should be worn to protect against blood or body fluids that may potentially splash the face / eyes. Place all sharps directly into a sharps bin; do not manually resheath or break needles. Do not overfill sharps bins, and ensure that the bin is securely fastened before disposal.

Place all sharps directly into a sharps bin; do not manually resheath or break needles. Do not overfill sharps bins, and ensure that the bin is securely fastened before disposal.ARTERIAL CANNULATION

Indications

Haemodynamic monitoring: particularly in situations where non-invasive measurements are inadequate, e.g. where changes in arterial blood pressure are likely to be sudden or profound, at extremes of blood pressure and in the presence of arrhythmias.

Haemodynamic monitoring: particularly in situations where non-invasive measurements are inadequate, e.g. where changes in arterial blood pressure are likely to be sudden or profound, at extremes of blood pressure and in the presence of arrhythmias.Procedure

Arterial cannulation. You will need:

Universal precautions; sterile gloves

Syringe of local anaesthetic / needle

Syringe of heparinized saline flush

Arterial cannulae (usually 20 gauge or 22 gauge)

Extension line and three-way tap

Decide which artery to cannulate. The radial artery of the non-dominant hand is usually preferred in the first instance. Alternatives include the ulnar, dorsalis pedis and posterior tibial arteries. It is pointless, however, to persist with attempts at peripheral arterial cannulation in patients who are hypotensive and ‘shut down’. The femoral and brachial arteries are useful during resuscitation of profoundly shocked patients. Ultrasound guidance is potentially useful at all sites to aid arterial cannulation, particularly in hypotensive patients and those whose landmarks are obscured by oedema or obesity.

Gently palpate the artery and inject local anaesthetic to raise a small intradermal bleb at the puncture site 1 cm distal to the proposed cannulation site.

Gently palpate the artery and inject local anaesthetic to raise a small intradermal bleb at the puncture site 1 cm distal to the proposed cannulation site.Seldinger technique

Advance needle through the puncture site towards the artery at a shallow angle. As the vessel is punctured, a flashback of arterial blood is seen in the hub. Pass the guide wire through the needle into the artery. Withdraw the needle and pass the cannula over the guide wire. The guide wire is then discarded.

Advance needle through the puncture site towards the artery at a shallow angle. As the vessel is punctured, a flashback of arterial blood is seen in the hub. Pass the guide wire through the needle into the artery. Withdraw the needle and pass the cannula over the guide wire. The guide wire is then discarded.Direct cannulation

Either: advance the cannula and needle through the puncture site towards the artery at a shallow angle. As the vessel is punctured a flashback of arterial blood is seen in the hub. Holding the needle still, advance the cannula over the needle into the artery. This should be a single smooth movement without resistance.

Either: advance the cannula and needle through the puncture site towards the artery at a shallow angle. As the vessel is punctured a flashback of arterial blood is seen in the hub. Holding the needle still, advance the cannula over the needle into the artery. This should be a single smooth movement without resistance. Or: advance the cannula at a steeper angle and, after observing the flashback, continue through the artery to transfix it. Withdraw the needle slightly from the cannula and then pull the cannula back gently until the tip is in the artery and flashback is again observed. Advance the cannula into the artery.

Or: advance the cannula at a steeper angle and, after observing the flashback, continue through the artery to transfix it. Withdraw the needle slightly from the cannula and then pull the cannula back gently until the tip is in the artery and flashback is again observed. Advance the cannula into the artery.Sampling from an arterial line

Samples for blood gases should be drawn into pre-heparinized syringes to prevent damage to the blood gas analyser. Any air in the syringe should be expelled. If not analysed immediately in the ICU, the syringe should be capped and placed on ice.

Samples for blood gases should be drawn into pre-heparinized syringes to prevent damage to the blood gas analyser. Any air in the syringe should be expelled. If not analysed immediately in the ICU, the syringe should be capped and placed on ice.USE OF PRESSURE TRANSDUCERS

The patient’s arterial catheter is connected to the transducer by a continuous column of (heparinized) saline. A pressurized flushing device maintains a small forward flow (approximately 2–3 mL / h) to keep the cannula patent.

The patient’s arterial catheter is connected to the transducer by a continuous column of (heparinized) saline. A pressurized flushing device maintains a small forward flow (approximately 2–3 mL / h) to keep the cannula patent. Pressure changes in the vessel are transmitted via the saline to a diaphragm. As this diaphragm moves in response to the pressure changes, its electrical conductivity changes. This results in fluctuations in electrical signal from the diaphragm, which is interpreted by a monitor and displayed as an arterial waveform and blood pressure values. Systolic, diastolic and mean pressures are usually displayed.

Pressure changes in the vessel are transmitted via the saline to a diaphragm. As this diaphragm moves in response to the pressure changes, its electrical conductivity changes. This results in fluctuations in electrical signal from the diaphragm, which is interpreted by a monitor and displayed as an arterial waveform and blood pressure values. Systolic, diastolic and mean pressures are usually displayed. There must be no air bubble in the connection tubing or transducer chamber. This will damp the trace and produce lower blood pressure values. Flush well before connecting the transducer to the patient.

There must be no air bubble in the connection tubing or transducer chamber. This will damp the trace and produce lower blood pressure values. Flush well before connecting the transducer to the patient. The transducer should be maintained at the level of the left atrium and appropriately zeroed. (If raised above this level the recorded pressure will be too low, and vice versa.)

The transducer should be maintained at the level of the left atrium and appropriately zeroed. (If raised above this level the recorded pressure will be too low, and vice versa.)Zeroing transducers

To zero a transducer turn the three-way tap so the transducer is open to air and the patient connection is switched off. The transducer is now connected to atmospheric or zero gauge pressure.

To zero a transducer turn the three-way tap so the transducer is open to air and the patient connection is switched off. The transducer is now connected to atmospheric or zero gauge pressure. Zero the monitoring system according to the manufacturer’s instructions. (There is usually a single button to press.)

Zero the monitoring system according to the manufacturer’s instructions. (There is usually a single button to press.)CENTRAL VENOUS CANNULATION

Indications

Central venous access is almost universal in intensive care patients. Indications include:

Ultrasound guidance for vascular access

The use of ultrasound to guide central venous access procedures is recommended in all cases (NICE Guidance. Central venous catheters, ultrasound locating devices, Sept. 2002. www.nice.org.uk/guidance/TA49).

Ensure correct orientation of the probe (vessels should be in the anatomical orientation as it would appear from where you are standing.

Ensure correct orientation of the probe (vessels should be in the anatomical orientation as it would appear from where you are standing. Identify patent target vessel. (To exclude thrombus in a vein ensure it empties completely with pressure.)

Identify patent target vessel. (To exclude thrombus in a vein ensure it empties completely with pressure.) Puncture the vessel of choice using real time guidance to direct the needle into the vein using longitudinal or transverse approaches.

Puncture the vessel of choice using real time guidance to direct the needle into the vein using longitudinal or transverse approaches.Traditional approaches to the central veins are described below.

Internal jugular vein

Right sided internal jugular vein cannulation is associated with a lower incidence of complications and higher incidence of correct line placement than other approaches. It is especially appropriate for patients with coagulopathy or those patients with lung disease in whom pneumothorax may be disastrous. It may be best avoided in those patients with carotid artery disease or those with raised intracranial pressure because of the risks of carotid puncture and of impaired cerebral venous drainage. Internal jugular cannulation is associated with a higher incidence of catheter infection than subclavian cannulation but both have a much lower infection rate than the femoral approach.

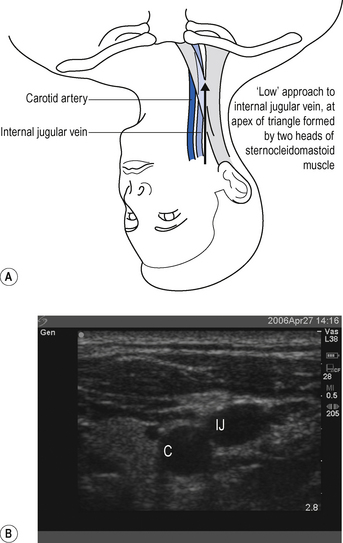

The internal jugular vein runs from the jugular foramen at the base of the skull (immediately behind the ear) to its termination behind the posterior border of the sternoclavicular joint, where it combines with the subclavian vein to become the brachiocephalic vein. Throughout its length it lies lateral, first to the internal and then common carotid arteries, within the carotid sheath, behind the sternomastoid muscle (Fig. 15.1A). Ultrasound demonstrates the close proximity of the vein to the carotid artery (Fig. 15.1B). Many approaches to the internal jugular vein have been described. A typical landmark approach is from the apex of the triangle formed by the two heads of the sternomastoid (Fig. 15.1).

Look for the internal jugular vein pulsation. If compressed, the internal jugular can usually be seen to empty and refill.

Look for the internal jugular vein pulsation. If compressed, the internal jugular can usually be seen to empty and refill. Introduce the needle from the apex of the triangle at an angle of 30° and aim towards the ipsilateral nipple.

Introduce the needle from the apex of the triangle at an angle of 30° and aim towards the ipsilateral nipple. Often when attempting to puncture the vein it collapses under the pressure of the needle and puncture is not recognized. The vessel may then be located by aspirating as the needle is slowly withdrawn. Blood is aspirated as the needle tip passes back into the vein, which refills once the pressure has been removed.

Often when attempting to puncture the vein it collapses under the pressure of the needle and puncture is not recognized. The vessel may then be located by aspirating as the needle is slowly withdrawn. Blood is aspirated as the needle tip passes back into the vein, which refills once the pressure has been removed. Typical catheter length required is 15 cm from the right and 20 cm from the left. The right side is preferred because left-sided catheters have to traverse two ‘corners’ to get to the SVC and are associated with a higher complication rate.

Typical catheter length required is 15 cm from the right and 20 cm from the left. The right side is preferred because left-sided catheters have to traverse two ‘corners’ to get to the SVC and are associated with a higher complication rate.External jugular vein

The external jugular vein lies superficially in the neck, running down from the region of the angle of the jaw, across the sternomastoid before passing deep to drain into the subclavian vein. It can be used to provide central venous access, particularly in emergency situations when a simple large-bore cannula can be used for the administration of drugs and resuscitation fluids. Longer central venous catheters can be sited via the external jugular but the angle of entry to the subclavian vein often leads to inability to pass guide wires centrally and results in a high failure rate.

Subclavian vein

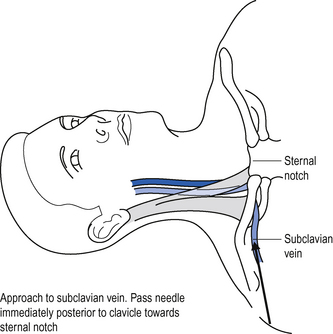

The subclavian vein is a continuation of the axillary vein. It runs from the apex of the axilla behind the posterior border of the clavicle and across the first rib to join the internal jugular vein, forming the brachiocephalic vein behind the sternoclavicular joint. See Fig. 15.2.

Position the patient supine (some people advocate placing a sandbag between the patient’s shoulder blades, which allows the shoulders to drop back out of the way).

Position the patient supine (some people advocate placing a sandbag between the patient’s shoulder blades, which allows the shoulders to drop back out of the way). Introduce the needle just beneath the clavicle at this point, and aim towards the clavicle until contact with bone is made.

Introduce the needle just beneath the clavicle at this point, and aim towards the clavicle until contact with bone is made. To locate the vein, redirect the needle closely behind the clavicle and towards the suprasternal notch.

To locate the vein, redirect the needle closely behind the clavicle and towards the suprasternal notch.Femoral vein

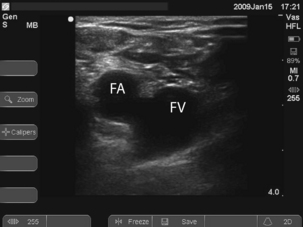

To locate the vein, introduce the needle 1 cm medial to the femoral artery close to the inguinal ligament. It is a common mistake to go too low where the superficial femoral artery overlies the vein. Long catheters, 24 cm plus, are required to get the tip of the catheter into the IVC, which may be required for good flows (e.g. for dialysis).

To locate the vein, introduce the needle 1 cm medial to the femoral artery close to the inguinal ligament. It is a common mistake to go too low where the superficial femoral artery overlies the vein. Long catheters, 24 cm plus, are required to get the tip of the catheter into the IVC, which may be required for good flows (e.g. for dialysis). Ultrasound can be used to identify the vessels and ensure that the vein is punctured near the inguinal ligament where the artery and vein lie side by side. See Fig. 15.3.

Ultrasound can be used to identify the vessels and ensure that the vein is punctured near the inguinal ligament where the artery and vein lie side by side. See Fig. 15.3.Procedure

Central venous cannulation. You will need:

Universal precautions; sterile gown and gloves

5-mL syringe of local anaesthetic

Heparinized saline to flush line

Ultrasound probe cover and sterile gel

Central venous catheterization is almost universally achieved using a catheter over a guide wire (Seldinger) technique. This is associated with a lower incidence of incorrect line placement and complications than cannula over needle techniques.

Central venous catheterization is almost universally achieved using a catheter over a guide wire (Seldinger) technique. This is associated with a lower incidence of incorrect line placement and complications than cannula over needle techniques. For internal jugular, external jugular and subclavian veins position the patient supine with 10–20° head down tilt. This distends the vein to aid location and helps prevent air embolism.

For internal jugular, external jugular and subclavian veins position the patient supine with 10–20° head down tilt. This distends the vein to aid location and helps prevent air embolism. Check wire passes through the needle freely. Attach three-way taps to all open ports of the cannula. Flush the lumens with heparinized saline.

Check wire passes through the needle freely. Attach three-way taps to all open ports of the cannula. Flush the lumens with heparinized saline. Using a 10-mL syringe and needle enter the central vein by the chosen approach, maintaining suction on the syringe at all times.

Using a 10-mL syringe and needle enter the central vein by the chosen approach, maintaining suction on the syringe at all times. Pass the Seldinger wire through the needle. This should pass freely and without any force into the vein. Watch for dysrhythmias. To reduce the risk of dysrhythmias, avoid introducing the wire further than necessary.

Pass the Seldinger wire through the needle. This should pass freely and without any force into the vein. Watch for dysrhythmias. To reduce the risk of dysrhythmias, avoid introducing the wire further than necessary. Never pull the wire back through the needle once it has passed beyond the end of the bevel: it may shear off.

Never pull the wire back through the needle once it has passed beyond the end of the bevel: it may shear off. If provided, pass the dilator over the wire into the vein. Then remove it, leaving the wire in situ.

If provided, pass the dilator over the wire into the vein. Then remove it, leaving the wire in situ. Pass the cannula over the wire into the vein. Make sure that before you push the cannula forward the wire is visible at the proximal end. Hold on to the wire at all times, to prevent it being lost inside the patient!

Pass the cannula over the wire into the vein. Make sure that before you push the cannula forward the wire is visible at the proximal end. Hold on to the wire at all times, to prevent it being lost inside the patient! For an average adult patient the central venous cannula does not need to be inserted more than 12–15 cm.Check markings on the cannula. Many are 20 cm long and do not need to be inserted up to the hub.

For an average adult patient the central venous cannula does not need to be inserted more than 12–15 cm.Check markings on the cannula. Many are 20 cm long and do not need to be inserted up to the hub. Draw back blood, flush all the lumens of the line with heparinized saline and lock off the three-way taps. At this point the patient can be levelled.

Draw back blood, flush all the lumens of the line with heparinized saline and lock off the three-way taps. At this point the patient can be levelled. Suture the line into place using the anchorage devices provided and cover with an adhesive sterile dressing.

Suture the line into place using the anchorage devices provided and cover with an adhesive sterile dressing. Obtain a CXR to verify position of the line and check for complications, including pneumothorax and haemothorax.

Obtain a CXR to verify position of the line and check for complications, including pneumothorax and haemothorax.Position on chest X-ray

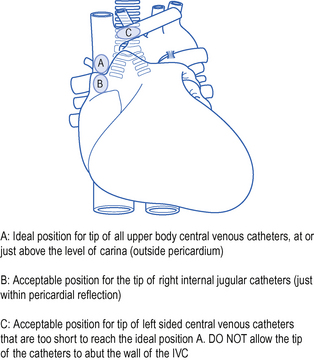

The catheter should lie along the long axis of the vessel and the distal segment and tip should be in the superior vena cava (SVC) or at the junction of the SVC and right atrium but ideally outside the pericardial reflection. Catheters below this level may perforate the heart and cause cardiac tamponade. The pericardial reflection lies below the level of the carina and this can therefore be used as a radiological marker. Catheters placed via subclavian veins of left internal jugular vein must not be allowed to lie with the tip abutting the wall of the superior vena cava. This may cause pain, perforation and accelerated thrombus formation. Either advance the catheter to lie in the long axis of the SVC or pull it back to lie in the brachiocephalic vein. See Fig. 15.4.

COMMON PROBLEMS DURING CENTRAL VENOUS ACCESS

Cannot find the vein

Check position (ultrasound and / or landmarks) and try again. If unsuccessful do not persist with repeated passages of the needle in the hope of striking oil! You may have misinterpreted the landmarks, or the vein may be absent or occluded (e.g. with thrombus). Seek help.

Complications

Complications of central venous cannulation depend in part on the route used but include those in Box 15.2.

Box 15.2 Complications of central venous cannulation

| Early | Late |

|---|---|

| Arrhythmias | Infection |

| Vascular injury | Thrombosis |

| Pneumothorax | Embolization |

| Haemothorax | Erosion/perforation of vessels |

| Thoracic duct injury (chylothorax) | Cardiac tamponade |

| Cardiac tamponade | AV fistula |

| Neural injury | |

| Embolization (including guide wire) | |

| AV fistula |

CHANGING AND REMOVING CENTRAL VENOUS CATHETERS

Line colonization with bacteria and fungi is common and there is no evidence that changing lines on a regular basis (e.g. every 5–7 days) is of benefit. (See Catheter-related sepsis, p. 340.)

Changing catheters over a wire

Pass the wire down the central lumen of the old central venous catheter. (Make sure that the new wire is longer than the old CVP line.)

Pass the wire down the central lumen of the old central venous catheter. (Make sure that the new wire is longer than the old CVP line.) Remove the old catheter, leaving the wire in place, and send the tip of the old catheter for culture.

Remove the old catheter, leaving the wire in place, and send the tip of the old catheter for culture.LARGE-BORE INTRODUCER SHEATHS / DIALYSIS CATHETERS

Indications

Introducer sheaths are available in a number of sizes for different applications, including insertion of pulmonary artery catheters and temporary pacing wires. In adults, 7.5 or 8.5 Fr are generally used. They may be used as large-bore access for volume resuscitation. Smaller sheaths may be used for introducing specialized monitoring such as jugular bulb oximetery. Large-bore double lumen dialysis catheters are used for haemodialysis, haemofiltration, plasma exchange and rapid transfusion.

Always seek senior help if you are not familiar with a procedure.

Always seek senior help if you are not familiar with a procedure.

If you do accidentally cut, scrape or puncture your skin, follow the ‘accidental inoculation procedure’, encourage bleeding, wash with warm soapy water, dry and cover with a waterproof dressing. Report the incident to the senior person in charge and ensure a report is completed. Seek advice from the occupational health department or A&E. In some cases, post-exposure prophylaxis may be required. This is time-critical, so seek immediate advice. It may be appropriate for someone else to complete the practical procedure.

If you do accidentally cut, scrape or puncture your skin, follow the ‘accidental inoculation procedure’, encourage bleeding, wash with warm soapy water, dry and cover with a waterproof dressing. Report the incident to the senior person in charge and ensure a report is completed. Seek advice from the occupational health department or A&E. In some cases, post-exposure prophylaxis may be required. This is time-critical, so seek immediate advice. It may be appropriate for someone else to complete the practical procedure.

Do not attempt central venous cannulation without supervision until you have been adequately taught to do so. You must be aware of possible complications and how to manage them.

Do not attempt central venous cannulation without supervision until you have been adequately taught to do so. You must be aware of possible complications and how to manage them.

Effective use of ultrasound requires practice. In particular the needle must be visualized as it passes into the vessel. Seek instruction before attempting to use it on a patient.

Effective use of ultrasound requires practice. In particular the needle must be visualized as it passes into the vessel. Seek instruction before attempting to use it on a patient.

It is a common mistake to assume the internal jugular vein is deep. Typically it is <2 cm from the skin. Do not introduce the needle to its full length. There is a danger of puncturing the apex of the lung.

It is a common mistake to assume the internal jugular vein is deep. Typically it is <2 cm from the skin. Do not introduce the needle to its full length. There is a danger of puncturing the apex of the lung.

If you appear to have missed the vein on the first pass, pull back slowly while maintaining suction on the syringe. You often find you have gone through the vein and can identify it on withdrawal.

If you appear to have missed the vein on the first pass, pull back slowly while maintaining suction on the syringe. You often find you have gone through the vein and can identify it on withdrawal.

Do not proceed immediately to attempt cannulation on the contralateral side: this increases the risk of complications, such as bilateral pneumothorax!

Do not proceed immediately to attempt cannulation on the contralateral side: this increases the risk of complications, such as bilateral pneumothorax!

The difficulty with this technique is retaining sterility, Wear two pairs of gloves and discard the top pair when you have removed the old line.

The difficulty with this technique is retaining sterility, Wear two pairs of gloves and discard the top pair when you have removed the old line.