13 Practical anatomy, examination, palpation and manual therapy release techniques for the pelvic floor

Female practical anatomy

Planes of examination

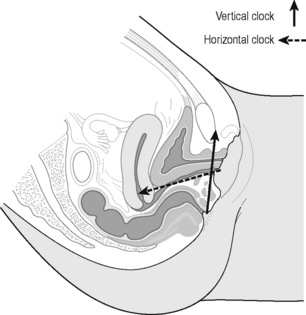

‘It is important to recognise that the pelvic diaphragm is not flat or bowl-shaped as is frequently depicted. At the urogenital and anal hiatus the muscles lie in a near vertical configuration and behind the anus they flatten to form a nearly horizontal diaphragm’ (Brooks et al. 1998). The examination of the patient most frequently takes place in the crook lying position. As the examiner faces the patient the perineum from the pubic bone to the supporting surface is visualized on a clock; this was first described by Laycock & Jerwood (2001).

During this part of the examination palpating from the vertical clock to the horizontal clock it should be visualized that the vagina extends inward from the vestibule at a 45° angle and then turns horizontal over the levator plate (Brooks 2007). The ‘horizontal clock’ runs for purposes of description perpendicular to the vertical but is clearly not completely perpendicular; the coccyx here is at 12 o’clock and the perineal body again is at 6 o’clock (Figures 13.1, 13.2) (Whelan 2008). It should also be stated that the pelvic floor and the structures of the pelvis are multidimensional and it can be difficult to visualize the many different planes. This suggested method of examination is based on two planes only but the examiner will appreciate the overlap into other planes.

Practical anatomy on the vertical clock – External perineal

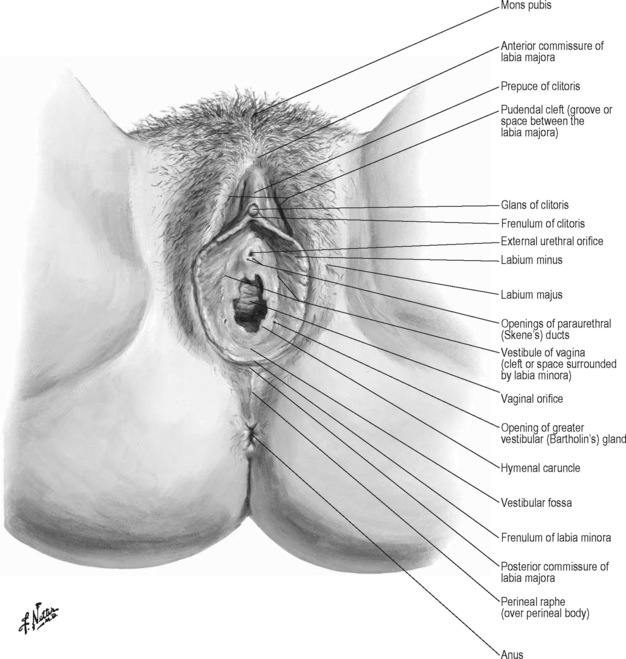

The examination on the vertical clock has two parts, the external first and then the internal. The external genitalia are observed for lesions, erythema and colour changes before the soft tissue assessment begins. The conditions that may affect the external genitalia in chronic pelvic pain are discussed in Chapter 8; however, the therapist should be familiar with symptoms and appearance of dermatological conditions such as dermatitis, lichens planus and lichens sclerosus and be aware of the occurrence of thrush and sexually transmitted infections including genital herpes and genital warts.

As the patient lies in the crook lying position the pubic bone is observed in the 12 o’clock position on the vertical clock and the perineal body is at 6 o’clock. The mons pubis is the area of skin overlying the pubic bone. Inferior to this is the anterior commissure of the labia majora; this is where the divide of the labia majora starts. The labia majora ends at the posterior commissure of the labia majora superior to the perineal body. Inferior to the anterior commissure of the labia majora is the area of tissue superior to the glans of the clitoris called the prepuce of the clitoris. Lateral here is the pudendal cleft which is the space between the labia majora. The frenulum of the clitoris is the area just below the clitoris. The labia minora start at the clitoris and extend down to the frenulum of the labia minora superior to the perineal body. The vestibule of the vagina is the space surrounded by the labia minora. Below the frenulum of the clitoris is the external urethral orifice and below this again is the vaginal orifice. Lateral to the vaginal orifice in the 5 o’clock and 7 o’clock positions are the openings of the Bartholin’s glands (Figure 13.3).

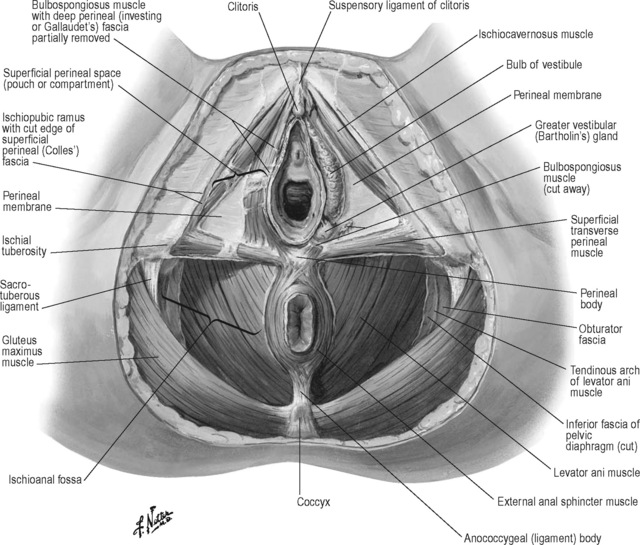

The perineal body is positioned between the posterior commissure of the labia majora and the anus; it forms the centre point of the perineum and lies deep to the external genitalia. Attaching to the perineal body centrally are the superficial transverse perineii muscles and they extend bilaterally to the ischial tuberosities. The ischiocavernosus muscles arise from the ischiopubic ramus and extend upwards to the crus of the clitoris. The bulbospongiosus muscles attach to the perineal body, the fibres run on either side of the vagina covering the superficial part of the vestibular bulb and vestibular glands and insert below the clitoris (Figure 13.4). Palpation of the bulbocavernosus and the transverse perineii is best performed by pincer palpation where the pad of the palpating finger is inserted just inside the vagina and met by the opposition of the thumb on the outside. The tissue is stretched or rolled between the finger and the thumb revealing the resting tone, tension, taut bands and trigger points. The ischiocavernosus is palpated against the ischiopubic ramus behind.

The deep perineal membrane extends from the ischiopubic ramus laterally to the vagina medially overlying what were previously referred to as the deep transverse perineal muscles but are the compressor urethrae muscle and the urethrovaginal sphincter muscles (DeLancey 1990). The urethrovaginal sphincter surrounds the vaginal wall and extends along the inferior pubic rami above the perineal membrane as the compressor urethrae. Superficial to these are the ischiocavernosus, bulbocavernosus and transversus perineii and the fascia superficial again to this layer is the superficial (Colles) fascia. The bulb of the vestibule is deep to the bulbospongiosus muscle and attaches to the deep perineal membrane. The perineal membrane is also referred to as the urogenital diaphragm (Herschorn 2004).

Practical anatomy on the vertical clock – Internal vaginal

The internal examination is started at the introitus with the pad of the finger palpating the perineal body, which is the central tendon of the superficial pelvic floor; resistance and length of the pelvic floor should be appreciated here. A short pelvic floor will be palpated where the dorsum of the finger just inside the vagina is held tight up against the pubic bone (Fitzgerald & Kotarinos 2003).

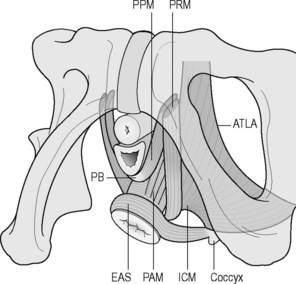

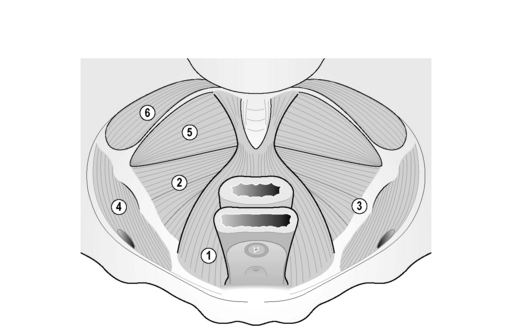

The anterior attachments of the levator ani muscle group are palpated on this plane by moving the palpating finger laterally to feel for resistance and attachment to the pubic bone. The most superficial part of the levator ani group is the puboperineal portion attaching from the pubic bone to the perineal body; the pubovaginalis muscle attaches from the pubic bone to the posterior vaginal wall and the puboanal portion inserts into the anal canal and skin (Figure 13.5). These muscles are part of the pubovisceralis muscle group, they were previously referred to as the pubococcygeus muscle but were renamed to reflect the orientation of the different parts of the muscle in the pelvic floor (Lawson 1974, Kearney et al. 2004). Now the pubococcygeus muscle refers distinctly to the muscle attaching from the pubic bone to the coccyx only. The puborectalis is distinct from the other pubovisceralis muscles as it attaches to the pubic bone and forms a sling behind the rectum and creates an angulation of the rectum whereas the other muscles elevate the anus perineal body and vagina (DeLancey & Ashton-Miller 2007).

Loss of attachment of the puborectalis will be palpated as bony end feel laterally on the pubic bone and high tone will be noted as thickened and resistant, often with acute pain at this point in the symptomatic patient. If the finger can be moved over the inferior pubic ramus without encountering any contractile tissue for 2–3 cm then this implies an avulsion injury to the puborectalis on that side. This may be the case in 15–30% of women who have given birth normally (Dietz 2009). This is compared from side to side. The palpating finger then tracks along the posterior vaginal wall evaluating resistance and this resistance can change from the vertical to the horizontal clocks as the pubovaginalis to the puborectalis muscles are palpated. The pubovaginalis or puborectalis muscles are short if the palpating finger is held up against the pubic bone. It may be difficult to stretch or lengthen the muscle and deep palpation may reveal a specific point of tension or a taut band within the muscle. There may be increased sensitivity in this localized taut band indicating the presence of a trigger point. On moving the finger slightly more posteriorly into the vagina, the rectovaginal fascia is palpated overlying the rectum, the rectum and its contents are palpated. Just lateral to the rectum, tone of the puborectalis is palpated, high tone will flex the palpating finger and there will be strong resistance on downward pressure.

The pad of the palpating finger is turned upwards towards the urethra. The anterior wall is covered by the pubocervical fascia and the urethra is palpated through this fascia. The pubocervical fascia extends from the symphysis pubis along the anterior vaginal wall to blend with the fascia that surrounds the cervix. The urethra is followed posteriorly behind the pubic bone up to the urethrovesical junction and finally the base of the bladder is palpated. Immediately in front of the cervix the base of the bladder rests on the vaginal wall (Brooks 2007). Descent of the anterior wall either low down or up higher is felt as a soft ‘bogginess’. The vesical neck should lie 2–3 cm above the insertion of the pubourethral ligaments and the inferior surface of the pubic bone (DeLancey 1990). The pubourethral ligaments form the periurethral connective tissue and attach to the white line of the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis close to its pubic end (Standring 2008).

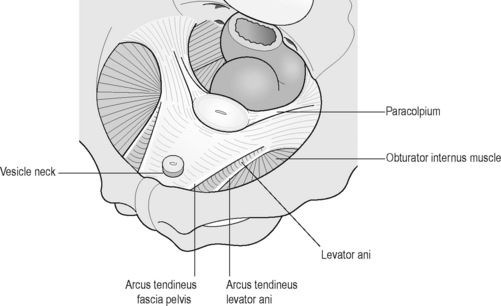

The urethra is palpated by a longitudinal or lateral stretch of the overlying tissue, sensation, resistance and painful points are evaluated. Posterior to and arising just lateral to the pubic symphysis is the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis (ATFP). The ATFP corresponds to the lateral attachment of the anterior bladder wall to the pelvic side wall and is joined by fibres of the superficial fascia of the levator ani. Its connection to the pubis lies 1 cm above the inferior margin of the pubic symphysis and 1 cm lateral to the midline (DeLancey 1990). The anterior portion is palpable at its attachment to the pubic bone and posteriorly it becomes less well defined and more difficult to palpate as it broadens out towards its attachment to the ischial spine (Figure 13.6).

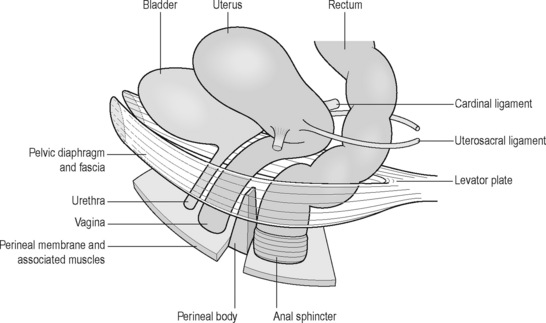

On palpation along the anterior wall of the vagina, the end point will be the anterior fornix. At this point the anterior wall is attached to the cervix of the uterus, the cervix is palpated and then the posterior fornix is palpated, depending on the position of the uterus, the posterior fornix may be difficult to palpate. The apex of the vagina is palpated and total vaginal length is noted. It is worth noting both position and the resistance of the uterus on palpation as clinical observation has shown this may change with treatment and can be retested. The paracolpium is the connective tissue surrounding the mid to upper vagina and uterus and fuses with the pelvic wall and fascia laterally. The cardinal ligaments extend from the lateral margins of the cervix and upper vagina and lateral pelvic walls, to an area expanding from the greater sciatic foramen to the piriformis and the lateral sacrum as far as the sacroiliac joints. The uterosacral ligaments are attached to the cervix and upper vagina posterolaterally and posteriorly to the fascia in front of the sacroiliac joints (Herschorn 2004). The paracolpium can be palpated but the uterosacral and cardinal ligaments are too deep to be palpated to their attachments. The apex of the vagina and uterus are held in place by the uterosacral and cardinal ligaments anchoring the pelvic viscera over the levator plate (Figure 13.7).

Practical anatomy on the horizontal clock – Internal vaginal

The examination so far has involved evaluation of the structures palpable in a circumferential and caudal to cranial direction. Now on examination of the deep pelvic floor the orientation changes in that the palpating finger examines across the posterior, lateral and posterolateral walls (Figure 13.2).

The palpating finger faces downwards towards the base of the spine and starts with palpation of the coccyx. The most posterior of the pelvic floor muscles is the ischiococcygeus attached from the coccyx to the ischial spine. Anterior to this is the iliococcygeus part of the levator ani group, a thin fan-shaped muscle extending from the tendinous arch of the levator ani (TALA) and with some fibres extending from the anus, to the last two segments of the coccyx (Figure 13.8). The fibres from both sides fuse and will form a raphe contributing to the anococcygeal ligament; this raphe is called the levator plate and provides shelf-like support to the organs. This is important for the configuration of the upper horizontal vaginal axis and support to the rectum and upper two-thirds of the vagina (Singh et al. 2001, Herschorn 2004).

The ischial spine is palpated as a bony point but the surrounding structures can have a taut end feel so it is not always easy to discriminate between bone and soft tissue. Anterior and inferior to the ischial spine is the pudendal nerve which can then be tracked anteriorly in Alcock’s canal (see Chapters 2.3 and 11.2). The obturator internus attaches to the TALA medially and the ilium laterally; it extends anteriorly to the pubic bone and posteriorly to the ischial spine. The belly of the obturator internus is palpated through the overlying obturator fascia; the obturator canal carrying the obturator nerve is palpated by tracking anteriorly towards the pubic bone.

The portion of the levator ani muscle attaching to the anal canal is named the puboanal muscle (Figure 13.8). The orientation here changes and the direction of stretch to determine resistance is towards the anus. The sphincter can be palpated vaginally by opposing the pad of the palpating finger overlying the sphincter and the thumb externally. Tension points can be successfully picked up using this method. A separate anal examination should also take place where indicated (see below).

The puboperineal and pubovaginalis portions of the levator ani have been described in the section on evaluation on the vertical plane; the puborectal and puboanal portions are described above. The pubococcygeal portion arises from the pubic bone and extends to its attachment at the coccyx; the term pubococcygeus can only properly be used to describe the few fibres that join bone to bone (Strobehn et al. 1996). It is palpated laterally to the puborectalis. The pubovisceralis muscle as described by Lawson (1974) is the correct term used to describe the levator ani muscle with its attachment primarily to soft tissue as well as to bone.

Practical anatomy of the male pelvic floor

Introduction

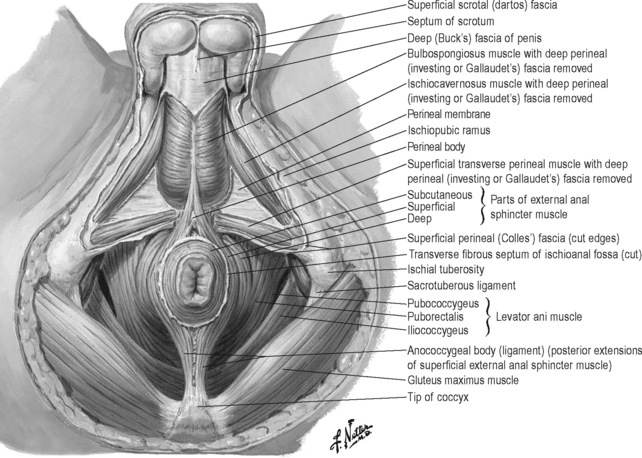

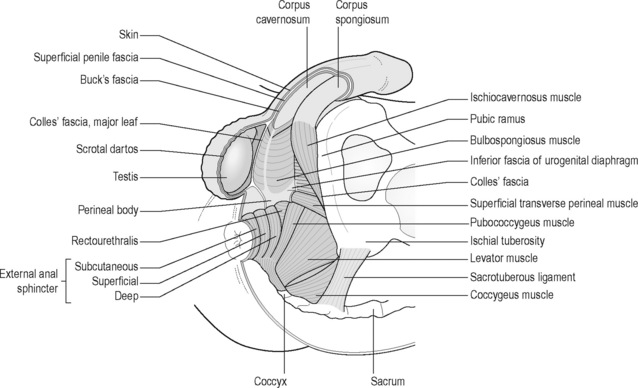

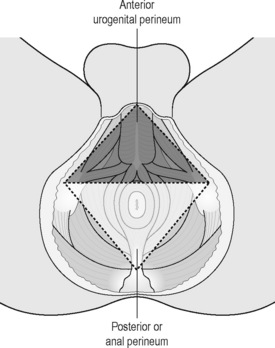

The male perineum has been described as fitting into two triangles: an anterior or urogenital perineum, formed by a line through the perineal body extending to the ischial tuberosities on either side and upwards to the symphysis pubis, and posterior perineal triangle formed by the base line through the perineal body and ischial tuberosities where the apex of the triangle is the coccyx (Figure 13.9). On most textbook anatomical views the anus and coccyx on this posterior triangle are depicted on exactly the same plane as the urogenital triangle; however, it can be observed clinically that the anus is slightly more posterior and the coccyx is even more posterior on the supporting surface with the patient in the crook lying position. The urogenital triangle can be useful when observing the structures on the perineum for orientation.

Figure 13.9 • Male perineum, urogenital triangle.

Reproduced from Anson, McVay (1984) Surgical Anatomy, sixth ed. WB Saunders

The vertical clock as described for the female pelvic floor is less practical here without the common access point anterior to the perineal body. Therefore the common base of the clock at 6 o’clock will be the anus with 12 o’clock as the pubic symphysis on the vertical clock and 12 o’clock as the coccyx on the horizontal clock, with the patient in supine crook lying position (see Figure 13.1). Structures accessed through the anus and rectum in a caudocranial direction circumferentially around the examining finger are described on the vertical clock; structures examined on the deep posterior and posterolateral wall are described on the horizontal clock.

Practical anatomy on the vertical clock – External perineal

On the urogenital triangle, the pubic symphysis is at the apex underlying the scrotum, which is lifted up for purposes of examination, and the perineal body is at the central point of the base of the triangle. Attached to the perineal body are the superficial transverse perineii muscles extending out to the ischial tuberosities laterally to the corners of the urogenital triangle. These corners are slightly below the central point of the perineal body. The bulbocavernosus attaches to the perineal body inferiorly and extends upwards inserting into the dorsum of the penis and the perineal membrane. The ischiocavernosus muscles arise from the ischiopubic rami laterally and cover the corpora cavernosa (Figure 13.10).

Practical anatomy on the vertical clock – Internal anal

The anal sphincter has an internal and an external component. The external anal sphincter surrounds the internal anal sphincter. The internal anal sphincter is a thickening of the inner circular smooth layer of the rectum. The external anal sphincter muscle has a subcutaneous, a superficial and a deep portion which are variable and often indistinct. The subcutaneous part attaches to the perineal body. The superficial part also attaches to the perineal body and to the coccyx as the anococcygeal raphe (Figure 13.11). At the posterior inflection of the rectum the deep sphincter blends with the puborectalis sling of the levator ani. Along the anal canal, posteriorly is the attachment of the puboanal portion of the levator ani muscle and fascia of the pelvic diaphragm. The corrugator cutis ani muscle situated around the anus is a thin layer of involuntary muscle fibre radiating from the orifice and blending with the skin. It raises the skin into ridges around the margins of the anus.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree