Introduction

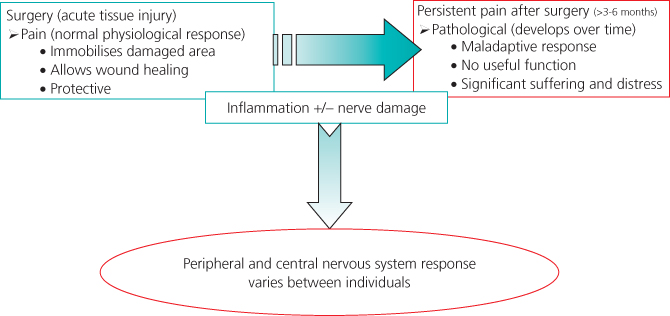

For the majority of patients, pain following surgery, while unpleasant, is usually a time limited event which should be well controlled with multimodal analgesia and ends with complete resolution of the pain (Figure 8.1). It is increasingly recognised, however, that a small proportion of patients continue to have significant levels of pain related to a surgical intervention beyond the anticipated time for resolution and that a number of these will develop chronic pain following surgery. As the duration of hospital stay after surgery is shortened, it is essential to ensure that acute post-surgical pain is managed optimally both in the inpatient and community settings.

This leads to two issues:

- What changes, if any, need to be made to standard post-operative multimodal analgesia to control prolonged post-operative pain?

- Is it possible to reduce the incidence of chronic pain related to surgery?

Assessment

There are four main groups of patients which have prolonged pain following surgery. Diagnosis of the problem and institution of appropriate management depends on taking a careful pain history and examination (Box 8.1). Failure to ask questions about the site and character of the pain make accurate diagnosis much harder. Some additional tools are also available if appropriate to the situation; these include neuropathic pain questionnaires such as the self-report Leeds Assessment of Neuropathic Symptoms and Signs (s-LANSS) (Chapter 6).

- Patients own verbal report of pain (where possible)

- Circumstances associated with onset of pain

- Pain intensity at rest and on movement (using pain assessment tool)

- Character (intermittent or constant)

- Location and radiation

- Exacerbating and relieving factors

- Effect of pain on other activities including sleep

- Current medications and other treatments for pain

- Associated symptoms (e.g. nausea)

- Previous or coexisting pain/medical conditions

- Vital signs – respiratory rate, pulse, blood pressure, SpO2

- Behavioural signs (facial expressions, crying, restlessness, guarding or rubbing of the affected area)

Aetiology of Prolonged Pain Following Surgery

Surgical Causes

The duration of pain following surgery will be protracted if surgical complications arise, such as a wound infection, where pain will remain in the surgical area. Alternatively, a patient may develop new pain resulting from a post-operative complication, for example pleuritic chest pain associated with a post-operative chest infection. It is important to take a history from the patient and undertake a thorough clinical assessment in order to diagnose these problems, since specific management is likely to be necessary and should resolve the problem. Continued multimodal analgesia is likely to be effective in controlling these types of pain.

It has been shown, however, that prolonged wound pain due to infection or haematoma is one of the risk factors for development of chronic postoperative pain (Figure 8.2).

Figure 8.2 A complicated post-operative course with wound infection may predispose to persistent pain.

Prior Pain Sensitisation

The pain pathway is a dynamic entity which not only provides pain signalling to the central nervous system but also undergoes a series of changes known as peripheral and central sensitisation in response to a continuing pain stimulus (Chapter 2). For the majority of individuals and/or pain episodes these changes would appear to be reversible. However, it is recognised clinically that there are some patients who appear to retain a ‘hyped up’ pain pathway and, while not suffering from chronic pain, do suffer from more severe and more protracted pain than might be anticipated. Again most of these patients respond well to multimodal analgesia but it may be necessary to use higher dosing schedules and slow the pace of step down analgesia.

Analgesic Tolerance

Patients who present for surgery who are already taking opioid medication, either therapeutically or off prescription, will have developed a degree of tolerance to opioids which makes effective post-operative pain management more difficult, particularly if an opioid-based technique such as patient-controlled analgesia is used. Again, these patients require a higher dose of opioids to be given and will usually take longer to step down their analgesia. It is also likely that at least some of these patients will have preceding pain sensitisation in addition to having tolerance. There is some evidence, for example, that patients on methadone maintenance for substance misuse may have lower pain thresholds.

Development of Neuropathic Pain

Taking a full pain history (symptoms suggesting neuropathic pain are outlined in Box 8.2) or using a neuropathic pain questionnaire, such as the s-LANSS, demonstrates that up to 10% of patients develop symptoms compatible with neuropathic pain post-operatively. A neuropathic component to the overall post-operative pain should probably also be considered if a patient has persistent poor pain control in the face of adequate levels of multimodal analgesia.

- Pain in the absence of ongoing tissue damage

- Pain in an area of sensory loss

- Paroxysmal or spontaneous pain

- Allodynia (pain in response to non-painful stimuli)

- Hyperalgesia (increased pain in response to painful stimuli)

- Dysaesthesia

- Characteristic of pain different from nociception (e.g. burning, stabbing)

- Poor response to opioids or increased opioid use

- Presence of major neurological deficit (e.g. brachial plexus injury)

Neuropathic pain is pain that is generated within the pain pathway either peripherally or centrally (or both) as a result of damage to the pathway as a consequence of surgery (Chapter 6). While a direct cause and effect is hard to prove, it is considered likely that development of neuropathic symptoms in the immediate post-operative period is a precursor to chronic post-operative pain.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree