PNEUMONIA

Pneumonia is an infection of the alveoli (the gas-exchanging portion of the lung) emanating from different pathogens, notably bacteria and viruses, but also fungi. Community-acquired pneumonia occurs in 4 million people and results in 1 million hospitalizations per year in the United States.1,2 Pneumonia is the eighth leading cause of death, particularly among older adults,3 and is the most common trigger for sepsis. Those who develop hospital- or other healthcare-associated pneumonia (acquired after placement in a care facility) often have infection from resistant organisms (Table 65-1).4,5

| Classification | Criteria |

|---|---|

| Community-acquired pneumonia | Acute pulmonary infection in a patient who is not hospitalized or residing in a long-term care facility 14 or more days before presentation |

| Hospital-acquired pneumonia | New infection occurring 48 or more hours after hospital admission |

| Ventilator-acquired pneumonia | New infection occurring 48 or more hours after starting mechanical ventilation |

| Healthcare-associated pneumonia | Patients hospitalized for 2 or more days within the past 90 days |

| Nursing home/long-term care residents | |

| Patients receiving home IV antibiotic therapy | |

| Dialysis patients | |

| Patients receiving chronic wound care | |

| Patients receiving chemotherapy | |

| Immunocompromised patients |

Pathogenic lung organisms are usually aspirated, especially in the hospital or healthcare setting (where eating is often not done sitting upright for dubious reasons), although inhalation is another potential route. Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pneumoniae can produce pneumonia from hematogenous seeding. Patients most at risk for pneumonia are those with a predisposition to aspiration, impaired mucociliary clearance, or risk of bacteremia (Table 65-2).

Aspiration risk

|

Bacteremia risk

|

Debilitation

|

Chronic diseases

|

Pulmonary disorders

|

| Bronchoscopy |

| Viral lung infections |

Some forms of pneumonia produce an intense inflammatory response within the alveoli that leads to filling of the air space with exudate and white blood cells. Bacterial pneumonia results in an intense inflammatory response and tends to cause a productive cough. Atypical organisms often trigger a less intense inflammatory response and create a milder or nonproductive cough.

In about half of patients with community-acquired pneumonia, no specific pathogen is identified. When an organism is identified, the pneumococcus is still the most common, followed by viruses and the atypical agents Mycoplasma, Chlamydia, and Legionella. Most patients with severe community-acquired pneumonia who were otherwise healthy have S. pneumoniae and Legionella as pathogens.

In up to 5% of cases, more than one pathogen exists. In nursing home residents, alcoholics, and those with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and depressed CD4 counts, all the common pathogens exist along with others rarely seen in other patients.

Patients with pneumonia frequently will present with cough (79% to 91%), fatigue (90%), fever (71% to 75%), dyspnea (67% to 75%), sputum production (60% to 65%), and pleuritic chest pain (39% to 49%).6 Despite described patterns of presentation, the variability in the individual symptoms and physical findings can make clinical diagnosis and differentiation from bronchitis and other upper respiratory tract disease difficult.7,8 Many types of pneumonia do not have a sudden and characteristic presentation, and many patients with pneumonia have an antecedent viral upper respiratory infection with coryza, low-grade fever, rhinorrhea, or nonproductive cough. Weight loss, malaise, dizziness, and weakness may be associated with pneumonia. Some of the atypical agents are associated with headache or GI illness. Occasionally, pneumonia is associated with extrapulmonary symptoms, including joint pain, hematuria, or skin rashes. Table 65-3 lists common pathogen and clinical feature correlations, all of which can vary or be absent in an individual patient.

| Organism | Symptoms | Sputum | Chest X-Ray |

|---|---|---|---|

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | Sudden onset, fever, rigors, pleuritic chest pain, productive cough, dyspnea | Rust-colored; gram-positive encapsulated diplococci | Lobar infiltrate, occasionally patchy, occasional pleural effusion |

| Staphylococcus aureus | Gradual onset of productive cough, fever, dyspnea, especially just after viral illness | Purulent; gram-positive cocci in clusters | Patchy, multilobar infiltrate; empyema, lung abscess |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | Sudden onset, rigors, dyspnea, chest pain, bloody sputum; especially in alcoholics or nursing home patients | Brown “currant jelly”; thick, short, plump, gram-negative, encapsulated, paired coccobacilli | Upper lobe infiltrate, bulging fissure sign, abscess formation |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Recently hospitalized, debilitated, or immunocompromised patient with fever, dyspnea, cough | Gram-negative coccobacilli | Patchy infiltrate with frequent abscess formation |

| Haemophilus influenzae | Gradual onset, fever, dyspnea, pleuritic chest pain; especially in elderly and COPD patients | Short, tiny, gram-negative encapsulated coccobacilli | Patchy, frequently basilar infiltrate, occasional pleural effusion |

| Legionella pneumophila | Fever, chills, headache, malaise, dry cough, dyspnea, anorexia, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting | Few neutrophils and no predominant bacterial species | Multiple patchy nonsegmented infiltrates, progresses to consolidation, occasional cavitation and pleural effusion |

| Moraxella catarrhalis | Indolent course of cough, fever, sputum, and chest pain; more common in COPD patients | Gram-negative diplococci found in sputum | Diffuse infiltrates |

| Chlamydophila pneumoniae | Gradual onset, fever, dry cough, wheezing, occasionally sinus symptoms | Few neutrophils, organisms not visible | Patchy subsegmental infiltrates |

| Mycoplasma pneumoniae | Upper and lower respiratory tract symptoms, nonproductive cough, headache, malaise, fever | Few neutrophils, organisms not visible | Interstitial infiltrates, (reticulonodular pattern), patchy densities, occasional consolidation |

| Anaerobic organisms | Gradual onset, putrid sputum, especially in alcoholics | Purulent; multiple neutrophils and mixed organisms | Consolidation of dependent portion of lung; abscess formation |

The physical examination in a patient with acute pneumonia may show evidence of alveolar fluid (rales), consolidation (bronchial breath sounds), pleural effusion (dullness and decreased breath sounds), or bronchial congestion (rhonchi and wheezing).7,8 Radiologic findings in pneumonia sometimes provide a specific pathogenic diagnosis (Table 65-3).

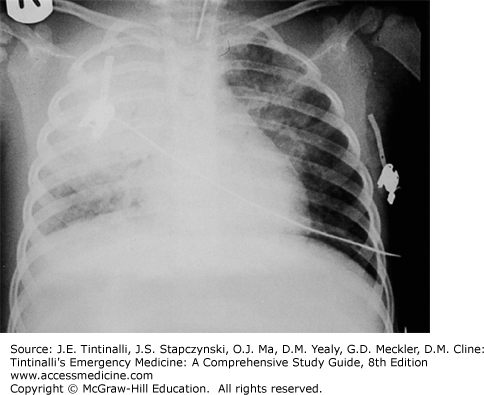

The elderly, children <2 years old, minorities, children who attend group day care centers, and those with immune-depressing comorbid conditions (e.g., previous splenectomy, transplantation, HIV infection, sickle cell disease) are at highest risk for pneumococcal pneumonia. Classically, patients with pneumococcal pneumonia present with sudden onset of disease with rigors, bloody sputum, high fever, and chest pain with lobar infiltrates (Figure 65-1); 25% will have parapneumonic pleural effusions. Patients with chronic lung disease, nursing home patients, or otherwise healthy elderly patients tend to have a slower progression of pneumonia, with symptoms of malaise with minimal cough or sputum production.

Laboratory findings in pneumonia include leukocytosis, elevation of the serum bilirubin or hepatic enzymes, and hyponatremia; none is diagnostic of the infection, but all detail the other organ involvement that can occur.

Pneumococcal pneumonia responds to a variety of antibiotics, although there is an increased incidence of penicillin-, macrolide-, and fluoroquinolone-resistant pneumococci.9 Penicillin resistance ranges from 5% to 80%, depending on location, with increasing resistance reported in Spain, Italy, and Eastern Europe. Resistance is also increasing to tetracycline and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. Patients with intermediate penicillin-resistant pneumococci may still be effectively treated with routine antibiotics so long as an adequate dose is administered.10 However, the bacteriologic agent is rarely known to clinicians at the start of therapy. Patients with highly penicillin-resistant pneumococci require treatment with vancomycin, imipenem, a newer respiratory fluoroquinolone, or ketolide.

S. aureus pneumonia is a consideration in patients with chronic lung disease, patients with laryngeal cancer, immunosuppressed patients, nursing home patients, or others at risk for aspiration pneumonia. S. aureus pneumonia may occur in otherwise healthy patients after viral illness, such as during an influenza epidemic, although pneumococcal pneumonia is still more common. Patients with staphylococcal pneumonia typically have an insidious onset of disease with low-grade fever, sputum production, and dyspnea. The chest radiograph usually demonstrates extensive disease with empyema, pleural effusions, and multiple areas of infiltrate (Figure 65-2). If leucocidin excretion by the organism accompanies this infection (rare and not predictable), rapid progression and death are common even with adequate therapy. Patients with healthcare-acquired pneumonia are at risk for infection with methicillin-resistant S. aureus.5,11

Klebsiella pneumonia often occurs in compromised patients: those at risk of aspiration, alcoholics, the elderly, and those with chronic lung disease. In contrast to S. aureus, patients with Klebsiella have acute onset of severe disease with fever, rigors, and chest pain. Patients with Klebsiella may develop pulmonary abscesses, although more commonly radiographs show a lobar infiltrate.

Pseudomonas causes a severe pneumonia with cyanosis, confusion, and other signs of systemic illness. The chest radiograph may show bilateral lower lobe infiltrates, occasionally associated with empyema. Pseudomonas is not a typical cause of community-acquired pneumonia, more often seen in patients with a prolonged hospitalization, who have received broad-spectrum antibiotics or high-dose steroid therapy, who have structural lung disease (including cystic fibrosis), or who are nursing home residents.

Haemophilus influenzae pneumonia occurs in any age, although it most commonly occurs in the elderly, or in those with chronic lung disease, sickle cell disease, or immunocompromised disorders and in alcoholics and diabetics. Since the onset of routine vaccination of children, the incidence of H. influenzae pneumonia in children has markedly dropped. Patients with this type of community-acquired pneumonia may either have a gradual progression of disease with low-grade fever and sputum production or occasionally the sudden onset of chest pain, dyspnea, and sputum production. Bacteremia may be seen in older adults. Pleural effusions and multilobar infiltrates are common findings in H. influenzae pneumonia.

Moraxella catarrhalis pneumonia has clinical features similar in spectrum to those of H. influenzae. Typically, patients with M. catarrhalis present with an indolent course of cough and sputum production, with fever and pleuritic chest pain are common. The chest radiograph usually shows diffuse infiltrates.

The atypical bacteria are Legionella, Chlamydophila, and Mycoplasma. Because these agents lack a cell wall, they do not respond to β-lactam antibiotics but respond to macrolides or a respiratory fluoroquinolone.

Legionella can cause a range of illness from benign self-limited disease to multisystem organ failure with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Patients at particular risk include cigarette smokers, patients with chronic lung disease, transplant patients, and the immunosuppressed. There is no seasonality to Legionella pneumonia, making it a more prominent cause of pneumonia in the summer when other pathogens decline in frequency. Legionella pneumonia is commonly complicated by GI symptoms, including abdominal pain, vomiting, and diarrhea. In addition, Legionella can affect other organ systems, causing sinusitis, pancreatitis, myocarditis, and pyelonephritis. The chest radiograph frequently shows a patchy infiltrate, with the occasional appearance of hilar adenopathy and pleural effusions (Figure 65-3).

Infection with Chlamydophila usually causes a mild illness with sore throat, low-grade fever, and nonproductive cough, although occasionally patients have a more severe course. Patients with Chlamydophila pneumonia frequently have rales or rhonchi. The chest radiograph usually shows a patchy subsegmental infiltrate, overlapping with the appearance of Legionella pneumonia. Chlamydial infection is linked to adult-onset asthma.

Mycoplasma pneumonia also occurs year-round, although it tends to cluster in epidemics every 4 to 8 years. Mycoplasma may cause a subacute respiratory illness with cough, sore throat, and headache. Mycoplasma pneumonia is also frequently associated with retrosternal chest pain. Unlike Legionella, Mycoplasma usually is not associated with GI symptoms. Like the other atypical pathogens, chest radiograph often shows patchy infiltrates, commonly with hilar adenopathy or pleural effusions. Mycoplasma occasionally causes extrapulmonary symptoms, including rash, neurologic symptoms, arthralgia, hematologic abnormalities, or rarely acute kidney injury. Bullous myringitis is not at all specific for Mycoplasma infection but is associated with many other causes of otitis media.

Viruses cause pneumonia, often severe; influenza is the most common viral pneumonia and is seasonal. The outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome and the Middle East respiratory syndrome, both from coronaviruses, demonstrates how a local infection can be rapidly transmitted worldwide.12 The most recent pandemic viral infection has been H1N1 in 2009. Varicella, typically benign in most childhood infections, can lead to a virulent pneumonia in pregnant patients. Further discussion of life-threatening viral infections is covered elsewhere (see chapter 153, “Serious Viral Infections”).

Suspect pneumonia from symptoms and signs (often fever, cough, dyspnea, or weakness with rales or rhonchi), while recognizing that each individual symptom or finding lacks high accuracy. When symptoms suggest a possibility, order a chest radiograph; if clinical findings suggest pneumonia (with or without an infiltrate on chest x-ray), treat emprically.13 No single set of recommendations for diagnostic testing applies to all patients, requiring clinical judgment. In otherwise healthy, mildly ill, ambulatory patients, no further ancillary testing may be necessary. To optimally risk-stratify anyone over 50 years old or more than mildly ill, seek evidence of other organ affliction; this is done by including CBC, serum electrolytes, BUN, creatinine, and glucose levels. Pulse oximetry is needed in all cases because a saturation on room air of <91% is associated with more complications. An arterial blood gas analysis is reserved for those appearing ill, with underlying lung disease, with oxygen desaturation, or in respiratory distress.

Most patients do not require identification of a specific organism through blood or sputum analysis to direct antibiotic treatment. The incidence of positive blood cultures in nonhospitalized patients with community-acquired pneumonia is low, pathogen identification usually does not alter treatment, and the majority of patients respond to empiric antibiotic treatment. The value of sputum culture is similar to the value of blood cultures and often limited by poor sampling, with less than 15% being adequate and helpful.14 Atypical agents may be detected by evaluation of titers from acute and convalescence sera or by direct fluorescent antibody testing.

In hospitalized community-acquired pneumonia patients, the incidence of positive blood cultures increases along with increasing disease severity.15 For this reason, obtain blood cultures in those admitted to the intensive care unit and in those with leukopenia, cavitary lesions, severe liver disease, alcohol abuse, asplenia, or pleural effusions.16 In any admitted patient, a sputum culture and Gram stain are options if an adequate sample can be obtained. Legionella urine antigen tests are useful in intensive care unit patients, alcoholics, those with classic findings, and those with a recent (within the past 2 weeks) travel history.

The differential diagnosis of patients with cough and radiographic abnormality includes lung cancer, tuberculosis, pulmonary embolism, chemical or hypersensitivity pneumonitis, connective tissue disorders, granulomatous disease, and fungal infections. Because radiographic signs of pneumonia vary, it is difficult to predict the causative microorganism by its radiographic appearance. In general, patients with bacterial pneumonia are more likely to have unilobar or focal infiltrates than patients with viral or atypical pneumonia. Hilar adenopathy is more common in patients with atypical pneumonia. Pleural effusions can accompany bacterial, viral, or atypical pneumonia. Cavitary lesions occur in patients with bacterial pneumonia or tuberculosis. Lung abscesses are rare complications of pneumonia in the antibiotic era, usually due to S. aureus or Klebsiella. Pneumococcal and staphylococcal pneumonia may mimic a lung mass, along with other atypical pneumonias, such as Q fever and tularemia.

Alcoholics have a higher risk than the normal population for many lung diseases, including pneumonia, tuberculosis, pleurisy, bronchitis, empyema, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Alcoholics are more likely than the general population to be undernourished, to develop aspiration pneumonitis, to be heavy smokers, and to have sequelae of alcoholic cirrhosis and portal hypertension. Compared with the nonalcoholic, the alcoholic has greater oropharyngeal colonization with gram-negative bacteria, and also has depressed granulocyte and lymphocyte counts with impaired neutrophil delivery.

S. pneumoniae is the most common pathogen causing pneumonia in alcoholics, but Klebsiella species and Haemophilus species are also important agents of infection. In general, rates of pneumonia and subsequent mortality are higher in alcoholics compared with nonalcoholic patients.

Diabetic patients between the ages of 25 and 64 years old are four times more likely to have pneumonia and influenza, and diabetics are two to three times more likely than nondiabetics to die with pneumonia and influenza as an underlying cause of death. Pathogens that occur with increased frequency in diabetic patients include S. aureus, gram-negative bacteria, mucormycosis, and Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infections due to S. pneumoniae, Legionella pneumophila, and influenza are associated with increased morbidity and mortality in diabetic patients.

Community-acquired pneumonia in pregnancy is one of the most serious nonobstetric infections, with maternal mortality of approximately 3%. Pregnancy does not alter the course of bacterial pneumonia, but the prognosis of viral pneumonia during pregnancy is more serious than in the nonpregnant patient. Pregnant woman are at risk for developing severe influenza-associated pneumonia, and antivirals are often used in this patient group (see chapter 153, “Serious Viral Infections”).

Pregnant women who develop varicella pneumonia are more often smokers and have skin lesions suggestive of the disease on exam. Obtain a chest radiograph and pulse oximetry measure in any pregnant woman with symptoms of respiratory tract infection and varicella exposure. Empiric IV acyclovir is often used, although there is little evidence that the timing of administration affects outcome.

Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia is the most common cause of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome–related death in pregnant women in the United States, with a mortality of approximately 50%; over half receive mechanical ventilation during hospitalization. Combination treatment with pentamidine, steroids, and eflornithine improves survival compared with patients treated with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole alone.

Pneumonia is the most common serious elderly infection, representing the fifth leading cause of death.17 The incidence of lower respiratory tract infection in the elderly ranges from 25 to 44 cases per 1000 in the general population, with a mortality rate approaching 40%. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, congestive heart failure, cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease, lung cancer, dementia, diminished gag reflex, and other aspiration risks make the elderly susceptible to infection.

Those over age 65 years are three times more likely to have pneumococcal bacteremia than younger patients. Atypical pathogens are still more common in younger populations but occur in the elderly. Legionella is the most common atypical agent in the elderly and is responsible for up to 10% of cases of community-acquired pneumonia. Influenza is the most common serious viral infection in the elderly. Postinfluenza bacterial pneumonia, whether following H1N1 or other seasonal influenza, is most commonly caused by S. pneumoniae, S. aureus, or H. influenzae. This usually presents as a worsening of respiratory symptoms after days of improvement.

Elderly patients with pneumonia may present with nonpulmonary symptoms like falls, weakness, tremulousness, functional decline, abdominal complaints, delirium, or confusion. Elderly patients are more likely to be afebrile on presentation but are more likely than younger adults to have a serious bacterial infection when the temperature is higher than 38.3°C (100.9°F).

Age alone does not confer a poor prognosis until extremes (over 85 years), but age does interact with other organ dysfunction to increase mortality and morbidity. Up to one third of elderly patients with community-acquired pneumonia will not manifest leukocytosis. Poor prognostic indicators for pneumonia in the elderly include hypothermia or a temperature >38.3°C (100.9°F), leukopenia, immunosuppression, gram-negative or staphylococcal infection, cardiac disease, bilateral infiltrates, and extrapulmonary disease. Elderly pneumonia patients frequently require hospitalization, and 10% receive intensive care.

Pneumonia is a major cause of morbidity, mortality, and hospitalization among nursing home residents.17,18 Nursing home patients are less likely than those living independently to have a productive cough or pleuritic chest pain, but more likely to be confused and have poorer functional status and more severe disease.18 Eight findings are independent predictors of pneumonia in nursing home patients: increased pulse rate, respiratory rate ≥30 breaths/min, temperature ≥38°C (100.4°F), somnolence or decreased alertness, presence of acute confusion, lung crackles on auscultation, the absence of wheezes, and an increased leukocyte count.19 A patient with one of these features has a 33% chance of having pneumonia, whereas three or more features suggest a 50% likelihood of pneumonia.19 Fewer than 10% of nursing home patients with pneumonia will have no respiratory symptoms. Fever, although nonspecific, is present in approximately 40% of cases of nursing home–acquired pneumonia.

The most frequently reported pathogens among patients with nursing home–acquired pneumonia are S. pneumoniae, gram-negative bacilli, and H. influenzae. Because nursing home patients live in close proximity to each other, residents are subject to outbreaks of influenza. Vaccination against influenza is 33% to 55% effective in preventing postinfluenzal pneumonia in nursing home patients. M. pneumoniae and Legionella are uncommon causes of pneumonia in nursing home patients.

Nursing home–acquired pneumonia is often treated in the hospital, but some patients can be treated in nursing homes with either intramuscular or oral antibiotics.20 Nursing home patients are at risk for the organisms linked to health care–associated pneumonia, so therapy should include coverage for gram-negative bacteria and methicillin-resistant S. aureus.4

Community-acquired pneumonia accounts for roughly three fourths of bacterial pneumonia diagnosed in patients hospitalized with HIV infection. Compared with HIV-seropositive patients hospitalized without pneumonia, those admitted with pneumonia generally have a lower CD4+ T-cell count, a higher Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II score, a longer length of hospital stay, a greater chance of intensive care unit admission, and a higher case fatality rate.

S. pneumoniae is the most common cause of bacterial pneumonia in patients with HIV. Pseudomonas aeruginosa is also a common cause of bacterial pneumonia in HIV-positive patients. HIV-positive patients with P. aeruginosa pneumonia, compared with HIV-negative patients, are more likely to have a lower leukocyte and CD4+ T-cell count and a longer hospital stay but a similar case fatality rate. (See chapter 154, “Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection.”)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree